Editor’s note: Emma Zhang reflects on her shifting identity as a language teacher in an age when machine translation threatens the role of English as a bridge to the world. Seeking cultural understanding, she visits Talibé, an exhibition by Mauritanian artist Saleh Lo, who paints haunting portraits of West African Qur’anic students trapped in poverty, exploitation, and outdated educational systems. Using repurposed tomato cans—symbols of global trade and survival—Saleh captures both despair and possibility, leaving faces unfinished to signify resilience and hope.

Saleh Lo’s Talibé exhibition runs until Monday 15 September 2025.

- Exhibition: “Talibé” by Saleh-Lo

- Address: 2/F, 16 Wyndham Street, Central, Hong Kong

- Dates: 29 July – 15 September 2025

- Hours: Tuesday – Saturday, 11:00 AM – 7:00 PM

- Inquiries: mwimbi@artbridger.com

I am not a connoisseur of modern art. I remain deeply sceptical of artists who tape a banana to the wall and call it Comedian, or place a glass of water on a shelf and call it An Oak Tree. What compelled me to travel from my Ta Kwu Ling home to the Talibé exhibition in Central, amidst a black rainstorm, was my recent identity crisis.

I come from Baoding, a small northern city near Beijing. In 1999, when I applied for a passport to travel to the United States, the local police officer did not know how to process the application, for no one in my district had ever travelled abroad. Yet I crossed the Pacific and discovered an entirely different way of life, solely because I had learnt English—a language that became my bridge to the wider world. Years later, I became a proud English teacher at Hong Kong Baptist University, believing I could bestow upon my students that same bridge to launch their global careers.

Now, however, with the growing accessibility and precision of AI-powered translation, language is no longer either a barrier—or a bridge. Theoretically, people may converse freely in their native tongues, relying upon instantaneous translation to convey meaning. Thus the very value of language teaching is brought into question. For this reason, I was charged not merely with imparting English proficiency, but also with introducing my wide-eyed first-year students to the world’s diverse cultures and traditions—transforming them into responsible global citizens. Yet how can a woman who has never lived outside China fulfil such a role? This is why, on Saturday 2 August, I endured a ninety-minute journey through blinding rain to visit the Talibé exhibition: to learn of the Talibé children of West Africa, young seekers of knowledge trapped in an ancient educational system brutally disfigured by globalisation.

Talibé means “a person seeking knowledge”. The word derives from the Arabic ṭālib, meaning “seeker” or “student”. In Mauritania, Talibé refers to children aged six to eighteen entrusted to the care of a marabout, a religious master, for spiritual education in a daara—a Qur’anic school. In colonial times, these schools were central in preserving Muslim cultural and religious identity against the Francophone Christian education imposed by colonisers.

After the founding of the Mauritanian nation, however, these Qur’anic schools faced profound challenges. Desertification, driven by climate change, impoverished nomadic communities, rendering livestock-herding unsustainable. Many families settled in rural or urban districts, yet the daara curriculum—consisting solely of Qur’anic memorisation and subsistence begging—remained unchanged. Once suited to the nomadic way of life, such a narrow education, devoid of languages, mathematics, science, or digital literacy, now ill-prepares its pupils for professional paths. Graduates find themselves confined to low-paid clerical work, or else become marabouts themselves. The expansion of the market economy has worsened matters: contributions once offered voluntarily to marabouts have become compulsory, with failure punished by corporal discipline.

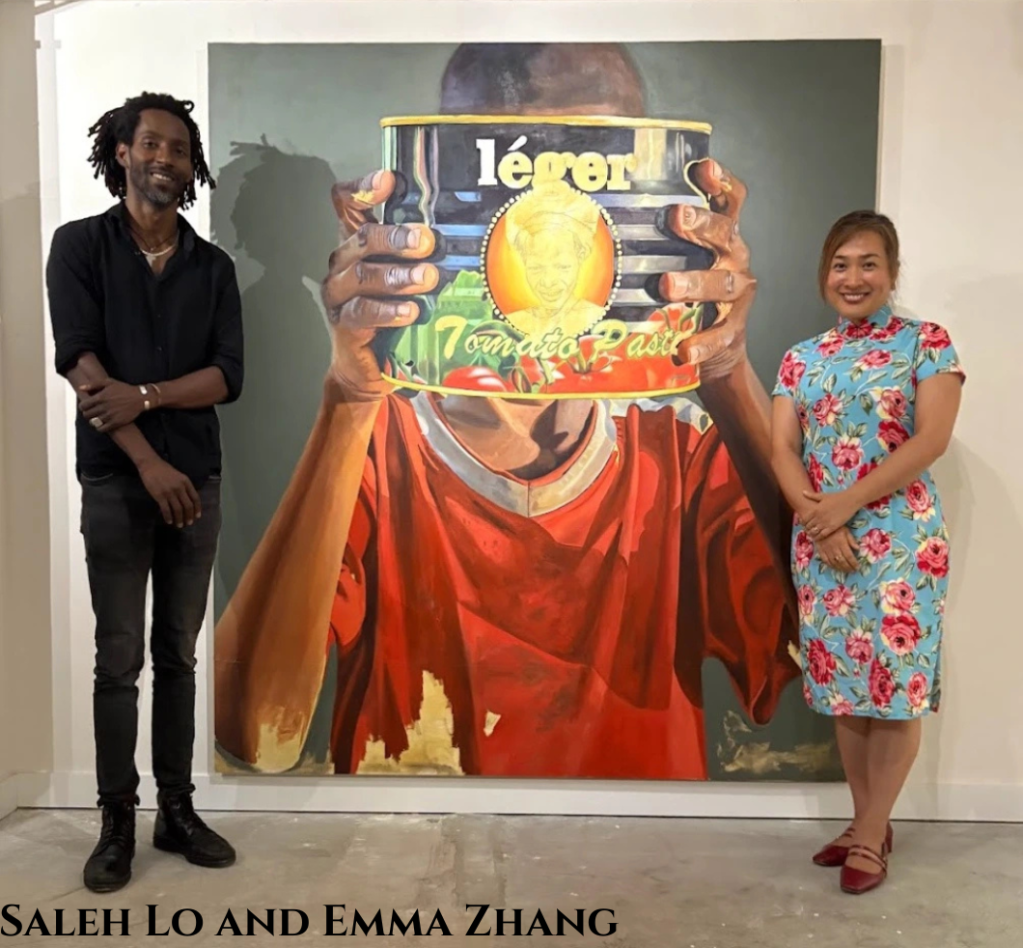

The artist of this exhibition, Saleh Lo, is a tall, lean young man whose father was himself a Talibé. Saleh grew up in a slum—“a world without art or artistic education”. As a young adult, he taught himself to paint by watching YouTube tutorials. Since then, his vivid portrayals of marginalised communities have earned him solo exhibitions in Nouakchott, Paris, and Mumbai—and now, Hong Kong. What has drawn him here is the humble can of tomato paste, twenty centimetres in circumference, one of Mauritania’s most common foodstuffs. These tins, mass-produced in China, contain a mere 28–30 per cent tomatoes. “What is the other 72 per cent?” I asked. Saleh shrugged: “I am here to find out.” He is undertaking a research project in China to investigate the production of this imported staple, now woven into Mauritania’s material life.

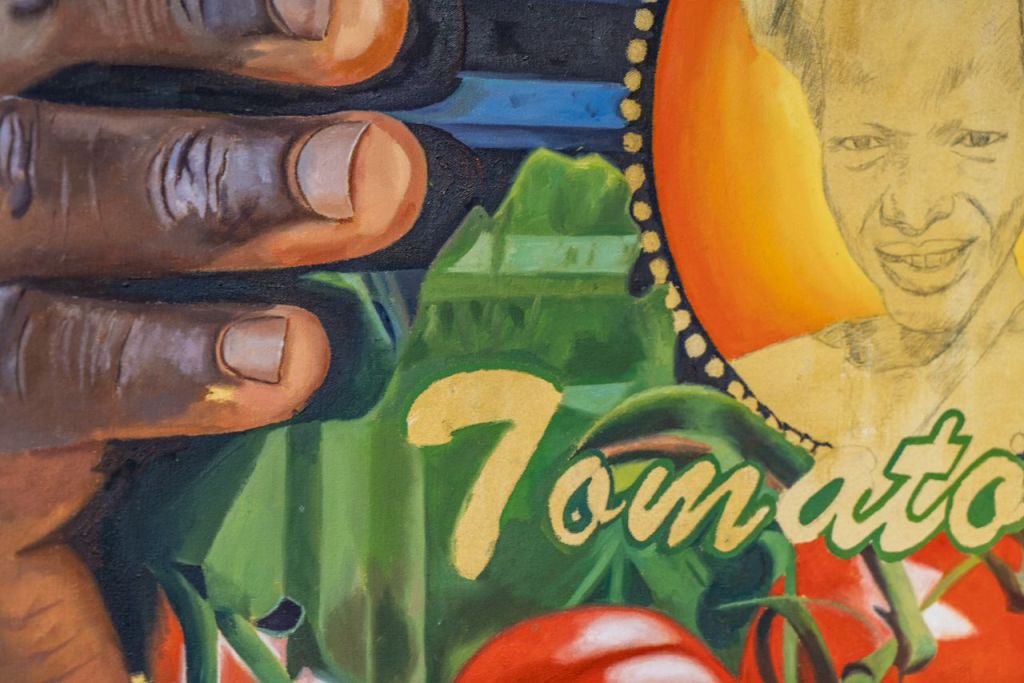

In the hands of Talibé children, these tins are repurposed into begging bowls—the very instruments of survival. All day they roam the streets, rattling the empty cans for food or coins to appease their marabouts. On meagre days, some choose to sleep rough rather than return to the daara, for fear of punishment. “I befriend the Talibé children, give them art lessons, and compensate them for their time,” Saleh said. By contrast, “the NGOs in their polished cars and high-ceilinged offices are doing nothing to help the Talibé children”.

Tins are repurposed into begging bowls—the very instruments of survival.

Mauritania is a nation of youth, its average age just nineteen. Many school-aged boys are Talibé from impoverished backgrounds, condemned to days of begging and Qur’anic recitation—pursuing knowledge that no longer serves them in a globalised age. Saleh transforms tomato cans into canvases, upon which he paints their faces: lives hemmed in by tradition and cut adrift from modernity. Some faces shine with innocence, others darken with fear or anger. None are finished. “I left them incomplete to represent hope,” Saleh explained. “These boys’ lives are unfinished—there is still space for them to flourish, if only we give them a chance.”

Last winter, I visited my former English teacher in Baoding. She told me the man who came to inspect her water metre held a master’s degree in mechanical engineering from a prestigious overseas university, yet the only work available to him was as a junior clerk in the local water bureau. As I stood before Saleh’s painting of a Talibé boy, his face wholly obscured by a tomato can, I asked myself whether I am equipping my students with the skills of a vanished past, whilst the ground beneath them shifts beyond recognition.

Saleh Lo in Central, Hong Kong

How to cite: Zhang, Emma. “Talibé: The Forgotten Faces of Globalisation” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 21 Aug. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/08/21/Saleh-Lo.

Emma Zhang teaches in the Language Centre at Hong Kong Baptist University. Her research interests include comparative literature and comparative mythology. Her doctoral dissertation Domination, Alienation and Freedom in Ha Jin’s Novels (2015) analyses Ha Jin’s novels in connection with contemporary Chinese society. Her other works include “Father’s Journey into Night” (2013), “No End in Sight—the myth of Nezha and the ultra-stable authoritarian political order in China” (2018), and “The Taming of the White Snake—The oppression of female sexuality in the Legend of the White Snake”. She is currently working on translating ancient Chinese legends Nezha and The Legend of the White Snake. [All contributions by Emma Zhang.]