茶 FIRST IMPRESSIONS

茶 REVIEW OF BOOKS & FILMS

[REVIEW] “The Dynasty that Dreamt in Red: Diamond Shumshere Rana’s The Wake of the White Tiger” by Abhinav Tulachan

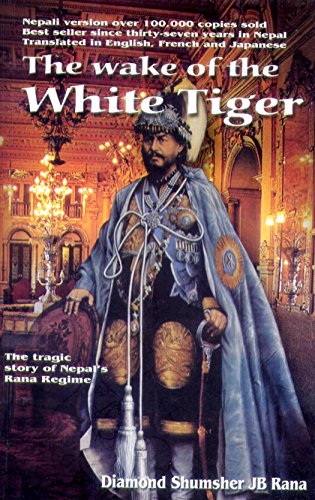

Diamond Shumshere Rana, The Wake of the White Tiger. 1984. 235 pgs.

“Looking back on the history of Nepal since the death of Prithvi Narayan Shah is to look back on a grotesque tale of intrigue, massacre and general political skullduggery… There were continuous struggles for power in which the palace would set up one family against another, struggles that would more often as not end in the shedding of blood.”

—Diamond Sumshere Rana, The Wake of the White Tiger. Chapter 28.

Brothers killing brothers. Nephews murdering uncles. Sisters scheming against one another for even the merest scrap of influence.

In Wake of the White Tiger (or Seto Bagh in Nepali [सेतो बाघ]), Diamond Shumshere Jung Bahadur Rana—writing from the rare and damning vantage point of both a Rana descendant and a political prisoner of that very regime—lays bare what can only be described as “the gilded cage” of Nepal’s century-long Rana dominion.

It is no exaggeration when he declares that Nepal’s history is written in blood. The road to power throughout its existence has been paved with the corpses of kith and kin—unceremoniously trampled upon to reach the summit; and perhaps the most bloodstained stretch of that road was painted at the height of the Rana regime.

A brief historical recap for the uninitiated: the Rana dynasty’s century of autocracy began in 1846 with the infamous Kot Massacre—in a single night of carnage in Kathmandu’s palace armoury, Jung Bahadur Rana, the dynasty’s founder, and his brothers slaughtered their political rivals, thereby securing their ascendancy. Seto Bagh resumes the tale decades after the bloody aftermath of that massacre.

Through a narrative at once historical testimony and Shakespearean tragedy, Diamond SJB Rana reveals how the dynasty’s original sin—power seized through blood—inevitably bred decay.

And it all begins, poignantly, with a romance doomed from its inception.

Yes, certain events are indeed dramatised for narrative effect (as the author himself concedes), but this scarcely detracts from the truth. If anything, it sharpens the story’s emotional edge while still preserving its essential historical weight.

At the novel’s centre lies the ill-fated love between the Princess Royal and Jagat Jung, Jung Bahadur’s eldest son, upon whom much of the drama revolves.

Jagat Jung is no ordinary man: ambitious and astute, charismatic yet seemingly refined, he is both adored and revered by the public. To the Princess Royal—who first hears of his exploits, becomes captivated by such a figure, and soon succumbs to infatuation, then love—it is a passion kindled by a profound desire to embrace this man. And it is a love that promises to immortalise the Jung dynasty’s supremacy.

Yet, even as this romance appears to gild the dynasty at its zenith, the narrative turns towards the shadows gathering at its base. For with every new height the Jung family ascends, their rise casts long, envious shadows below—shadows where the Sumshere brothers, Jung Bahadur’s neglected nephews, fester in resentment and envy.

Even without the political or historical context, it is difficult not to pity the Sumshere family’s poverty. They are depicted as the ostracised branch of the clan—the youngest, and thus the last in line to inherit titles from the dominant Jungs. The author demonstrates with devastating clarity how deprivation fuelled the eventual fratricidal conflict, serving as a humiliating indictment of their place within the family hierarchy. By the third chapter, the mockery of their situation is already evident: threadbare garments mended beyond dignity; the absence (and yearning) of the gold and silver jewellery flaunted daily by their cousins; the palpable air of shabbiness that pervades their quarters. Once again, it is impossible not to pity the Sumshere family, left to rot and all but forgotten—save by Jung Bahadur himself—in the clan’s relentless ascent to supremacy.

And when news arrives that Jagat Jung is to wed the Princess Royal—the very woman once promised to Bir Sumshere (by Jung Bahadur as a means of preserving peace with his brothers)—that moment, subtle at first yet seismic in consequence, is when envy germinates into something altogether more lethal: resentment.

All the while, the founder Jung Bahadur strives to quell the very bitterness he himself has predetermined. Diamond Shumshere depicts with precision the calculating tactician that Jung was: the man who seized power in a single night; the man who deftly distributed titles, patronages, and marriages to bind both brothers and royals in loyalty.

Every tale of Jung Bahadur’s brilliance recounted in schoolbooks, every grand feat my grandparents once extolled, I dare say, finds its most vivid expression in Diamond Shumshere’s portrait of him.

Yet, for all his foresight, even Jung’s grandest designs cannot forestall fate—or the toll of age.

In the novel’s most haunting sequence (a section that still compels me to slow my reading, to linger over each passing moment), Jung Bahadur lies stricken after a hunting expedition. In his delirium, he swears he has seen a white tiger prowling the Terai grounds—an omen of death and ill fortune.

And in that instant, mere minutes before his death, he perceives the blood-soaked legacy he leaves behind: every scheme, every coup, every triumph, destined to collapse in the inevitable conflict between his sons and his embittered brothers.

“… even on his death-bed, Jung Bahadur dare not, nor could not, loosen his grip… He thought of the inevitable clash that would come after his passing: on one side his brothers with Dhir, on the other his sons, and ever and ever threatening in the background the seventeen sons of Dhir Sumshere.”

“He tried to voice his fears, but couldn’t.”

—Chapter Twenty-Five.

In this light, the white tiger Jung Bahadur beheld in his final hours assumes a new, haunting significance. A creature traditionally emblematic of royalty and strength—of majesty and pride—now appears drained of colour, pale as a spectre, embodying the fading power of the Ranas themselves.

Jung Bahadur had ensured loyalty by elevating his brothers and nephews to positions of immense power and wealth, binding them to the regime. Yet upon his death, the collapse only seemed to hasten. The dynasty’s founder had been the sole thread holding its fabric together, and with that thread severed—through both his demise and the ensuing turmoil—the very calculus that had secured the dynasty now became its poison.

The Sumshere brothers were no fools. They knew their station in the hierarchy was fixed, their “titles” little more than honourary. But blood, as they had observed, was the true currency of power. And if the Jung dynasty had seized the throne through massacre, the Shumshere brothers saw no reason not to follow that same bloodstained blueprint.

As the novel advances towards the inevitable rupture, this quiet fury swells into a powder keg poised to ignite. Political paranoia festers. Alliances shift like desert sands. Loyalties are traded with sickening ease, and the people embody the vilest opportunism: hailing the Jungs when their banners soar, eager for patronage and scraps of favour, only to desert them in droves when fortune falters—then circling back the instant power changes hands.

It is… saddening, almost cynical, to witness how men and women are driven less by loyalty than by self-interest—forever chasing the promise of a pittance of favour. It is a grimly accurate reflection of Nepal’s history, where survival has so often outweighed principle, even to this day.

And though the narrative veers at times towards melodrama, the author deftly wields this moment as a microcosm of the larger malady consuming the Rana clan: the absolute subordination of human bonds—love, loyalty, even filial piety—to an insatiable hunger for power, and the way such hunger corrodes the very fabric of the royal court. Everything is political, everyone a potential threat, no relationship immune to the corrosive touch of absolute rule.

Yet before I digress further, within this struggle Jagat Jung finds himself ensnared—less a kingmaker than a sacrificial pawn in the power vacuum created by the deaths of the King and Crown Prince. Even as Ranodip Singh, Jung Bahadur’s half-brother, assumes the premiership and gestures towards reconciliation, the Shumshere brothers’ resentment runs far too deep to be quelled. For them, the only way forward is once again through blood.

What renders the Sumsheres’ coup all the more chilling is how precisely it mirrors the methods of their predecessors. Just as the Jung brothers had once stood behind Jung Bahadur on the night of the Kot Massacre, so now do the seventeen Shumshere brothers rally behind their eldest, Bir, to stage their own massacre. The same strategic alignment—numerical unity—that had once cemented the regime is now repurposed to annihilate it. The implication is devastating.

What follows is inevitable: betrayal, assassination, the brutal erasure of Jagat Jung, his faction, his wife, and even their young son. The Jung family is hunted like wild game, cut down like dogs, in a slaughter that eclipses even the savagery of the Kot Parva.

And the people? Their loyalties had long since shifted to the Shumshere. Their soldiers? Motivated by rank and coin, they became the very instruments that brought down the doomed Jung faction. In Rana’s telling, whether the Kot Massacre had ever occurred, history was bound to reveal an equally grim spectacle of power claimed through blood.

As Nepal continues to reckon with its past and to forge a democratic future, Wake of the White Tiger endures as both reminder and warning: that without justice, without compassion, without true love and loyalty to land, liege, and people, even the most resplendent empires will bleed themselves to ruin from within.

How to cite: Tulachan, Abhinav. “The Dynasty that Dreamt in Red: Diamond Shumshere Rana’s The Wake of The White Tiger.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 18 Aug. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/08/18/white-tiger.

Abhinav Tulachan is an undergraduate student in the Department of English Language and Literature at Hong Kong Baptist University. He loves reading, writing, and sharing the knowledge he has gained through his academic journey. [All contributions by Abhinav Tulachan.]