📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

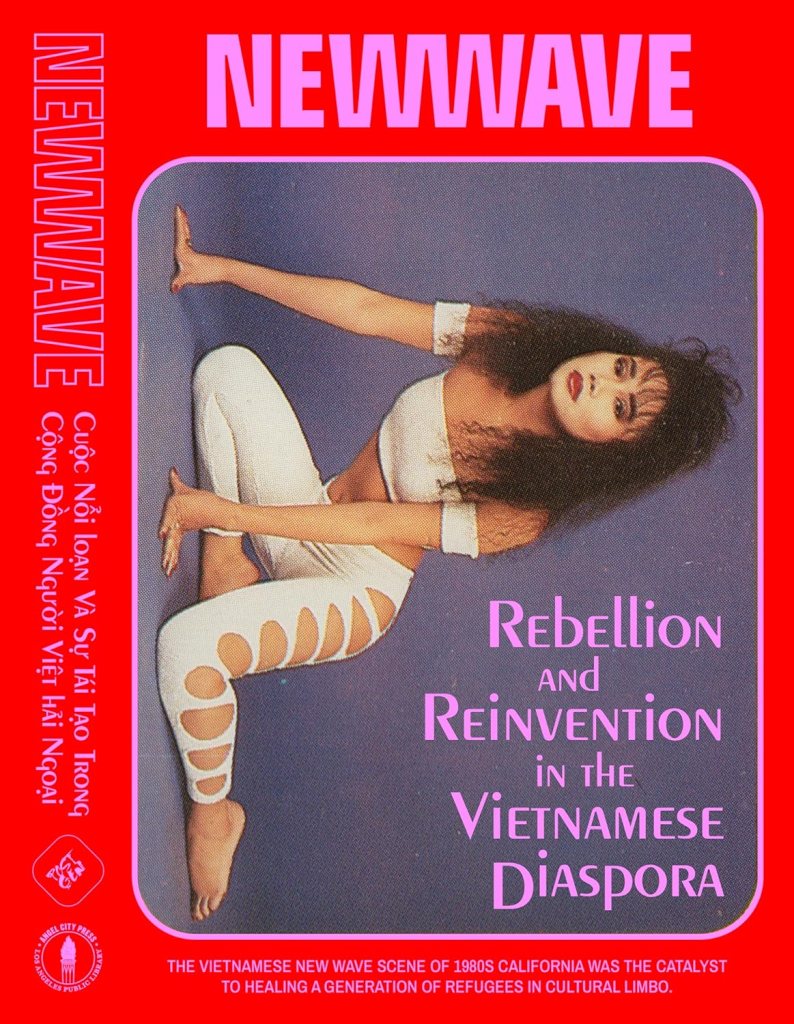

Elizabeth Ai (editor), New Wave: Rebellion and Reinvention in the Vietnamese Diaspora, Angel City Press, 2024. 192 pgs.

Elizabeth Ai’s edited volume New Wave: Rebellion and Reinvention in the Vietnamese Diaspora is not a work of rigorous academic research, yet scholars from across the arts and humanities will still find a wealth of resourceful material within its pages—a lively, mobile archive in printed form. This archive, as substantial and visually rich as a hardcover photo book, offers a meticulous portrait of how Vietnamese American communities grew and flourished during the first decades of resettlement. It does so through oral testimonies and visual fragments—family snapshots, as well as images drawn from collective, mainstream entertainment media.

Eleven contributors from diverse professional backgrounds—artist, scholar, poet, singer-songwriter, DJ, and community activist—share their memories and experiences as Vietnamese New Wave teenagers of the 1980s. The volume opens in Chapter 1 with the arrival of Vietnamese refugees after 1975, presented through two historical essays by Thúy Đinh and UCLA Professor Thúy-Võ Đặng. Chapter 2 turns to the struggles of the “1.5 generation”, caught between the enduring traditional customs of their parents’ and grandparents’ generations and the realities of life shaped by the American educational system and culture.

The central focus of the book—Chapter 3—is a detailed exploration of the Vietnamese “New Wave” generation. Essays by Thao Ha, Lan Duong, and Thúy-Võ Đặng offer a kaleidoscopic portrait of these teenagers’ rebellious coming-of-age years, as they broke with familial and cultural norms, asserting distinctive visual and musical tastes. Chapters 4 and 5 extend this exploration, animating the New Wave image through personal diary entries, public confrontations, oral histories, and nostalgic recollections.

Many of the contributors, now creative practitioners based across the United States, have opened their personal archives to the public, uniting their narratives in a collective act of remembrance—an undertaking that mirrors Elizabeth Ai’s work in both her documentary and this anthology. The result is not only a celebration of youthful rebellion and cultural reinvention but also a meaningful historical record of lived experience.

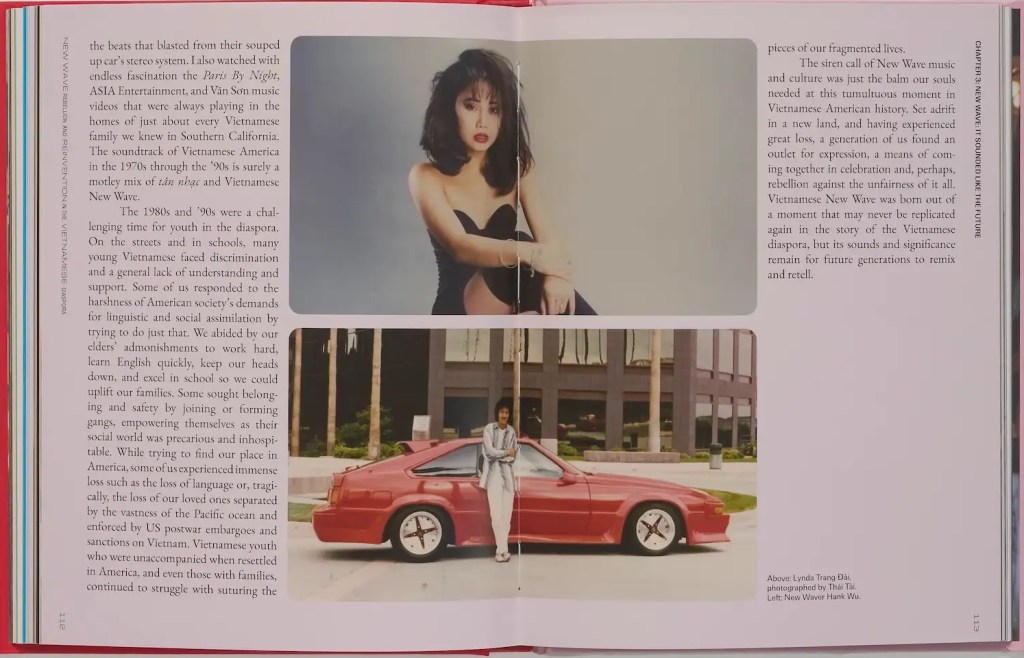

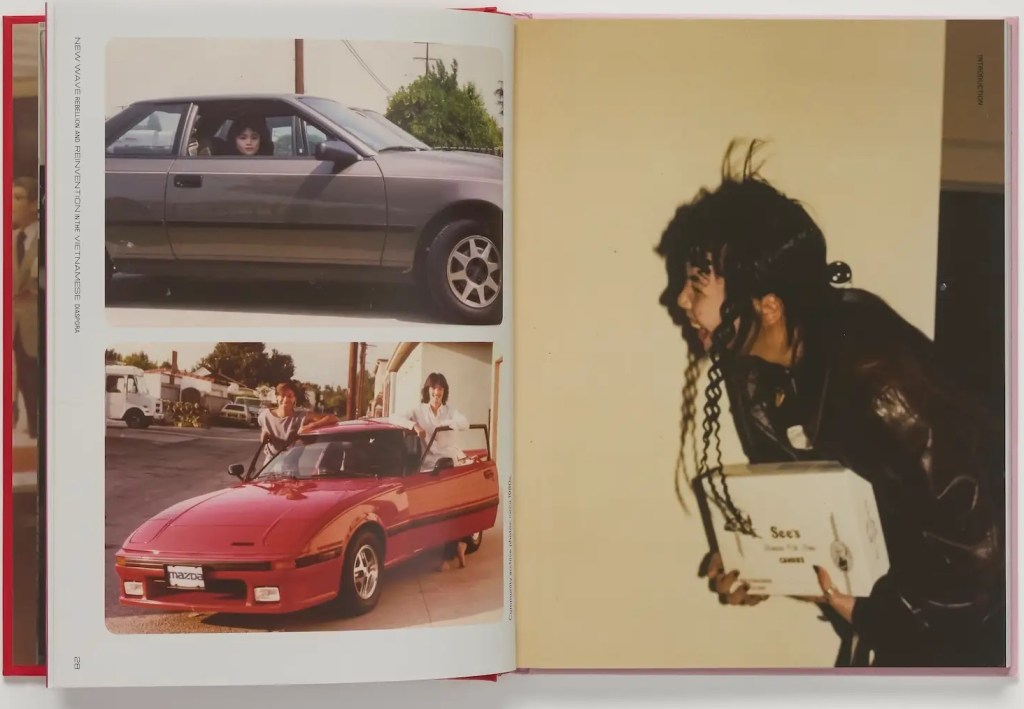

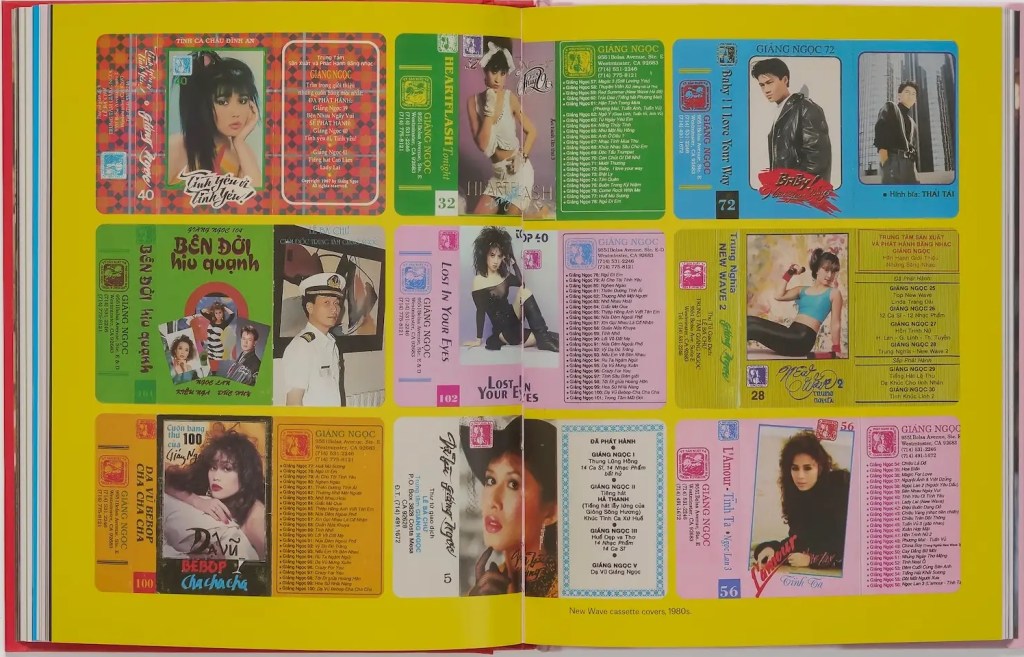

That being said, what draws one to this anthology is not merely the verbal narratives but also the wealth of vivid visual material—from personal family photo albums to sets of music CD covers—that fills this mini-archival catalogue with concrete evidence of the New Wave generation. Personal photographs contributed by the book’s authors are interwoven with textual narration and with the celebrity photoshoots that dominated the Vietnamese American cultural scene at the time. The cover features none other than Lynda Trang Đài—hailed by fans as the Vietnamese Madonna—a New Wave icon who defied not only visual but also sonic conventions in the formative years of the diasporic Vietnamese American entertainment industry.

As the pages turn, more Vietnamese celebrities appear alongside, and between, archival images of the authors’ teenage years. These include Ngọc Lan (Icon of Romantic Songs), Trizzie Phương Trinh, Thái Vũ, the children of renowned composer Phạm Duy—Thái Hiền, Thái Thảo, and Duy Quang—Kiều Nga (recently deceased), Don Hồ, and the singer-photographer Thái Tài, whose work helped preserve these precious moments in New Wave performance history. In works such as Ai’s New Wave, the visual components assume a central role, redirecting attention towards the non-verbal artefacts, which often evoke even deeper memories for those who lived through the era. The music swells to full volume; the dance floor is poised; the performers step out in their glittering discotheque attire and punk-rock boots, jeans, and shirts—and the party begins.

The book may be viewed as a companion piece to Ai’s documentary of the same name, yet for me, it stands firmly as an independent archival work—an alternative way of visualising Vietnamese American youth of the 1980s as they navigated the difficult choices between cultural assimilation and transnational integration. Watching the documentary is to be drawn into a crafted audio-visual narrative, where testimonies, archival footage, and vintage family photographs are arranged according to the director’s vision. Reading the book, however, is akin to entering an archival centre—confronted with primary materials of the same kind, but free to curate one’s own reading and interpretation.

It calls to mind another photo book, led by Leon Lê, the Vietnamese American director who made his Vietnamese debut with the 2018 film Song Lang. A year later, Song Lang: Nhìn Lại (Song Lang: A Look Back) adopted a similar approach to Ai’s New Wave—uncovering behind-the-scenes stories of the film’s production, alongside interviews and scholarly essays on a rare Vietnamese art-house film that ventured beyond the domestic market to achieve international recognition.

As a much later immigrant to the United States, my reading of the book was not driven by a search for scientific or historical certainties about the New Wave generation. Rather—and I applaud the creators for making their source materials accessible across multiple media—it became, for me, a tender imagined conversation with the New Wave children and the emerging Vietnamese Americans who had absorbed, reshaped, and resisted the hierarchies of an Americanised culture.

Some of my earliest impressions of Vietnamese America came via the well-worn CDs and DVDs of the immensely popular Paris by Night series in the early 2000s. Now, through Ai’s New Wave, I have gained deeper insights into earlier youth generations—several decades before my own teenage years—yet whose experiences bear strikingly similar traits in the negotiation of traditional familial expectations and finely grained national identity.

I am deeply grateful to the book for granting me the chance to step into another era of Vietnamese American community life—an experience that has enriched my own existence as an active member of the diaspora, and deepened my appreciation for the growth and expansion of Vietnamese identities across the global stage and through the passage of time.

Extra discography:

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=58PZjMJcVqw

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MUqC2kanvH0

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FDpHxTTNhxg

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8YBE2K6FVxo

How to cite: Tiến, Nguyễn Minh. “Archival Rhythms—Youth, Identity, and Cultural Resistance in the Vietnamese Diaspora: Elizabeth Ai’s New Wave.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 17 Aug. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/08/17/new-wave.

Nguyễn Minh Tiến is presently undertaking a master’s degree in Theatre and Dance (with a concentration in Performance Studies) at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, alongside a master’s degree in History at the University of Edinburgh. He holds two bachelor’s degrees: one in Art and Media Studies from Fulbright University Viet Nam, and the other in Literature from the University of Social Sciences and Humanities, Vietnam National University, Ho Chi Minh City.