📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

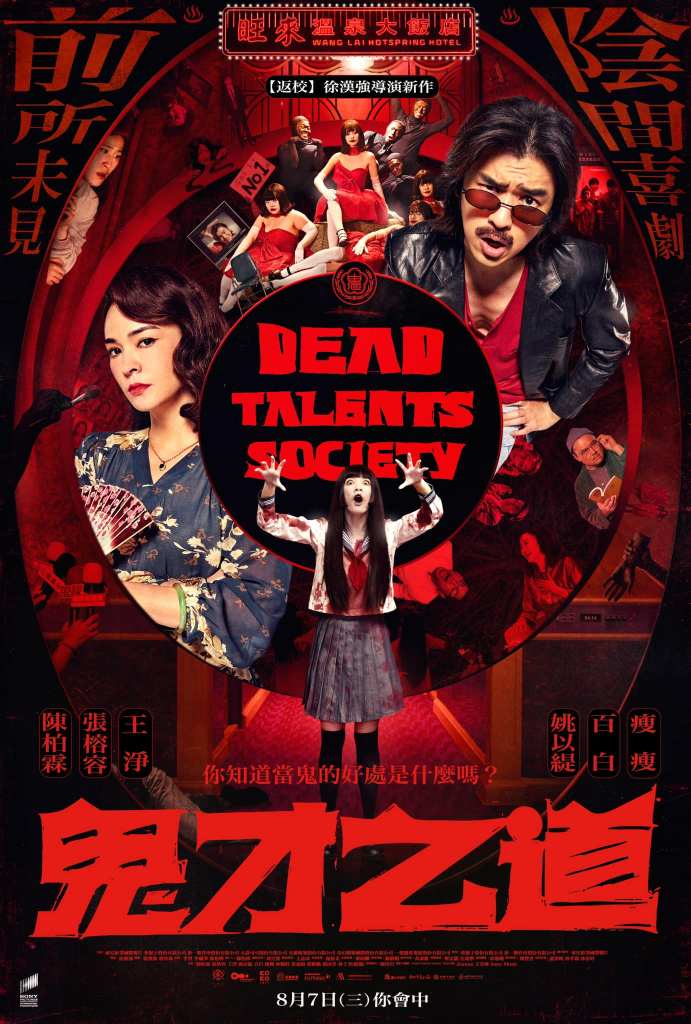

John Hsu (director), Dead Talents Society 鬼才之道, 2024. 105 min.

Put aside the spine-chilling horror of Nosferatu: what if the realm of the dead had its own celebrity influencers, and what if said influencers simply longed to be embraced and reassured by their fellow ghosts that they mattered? John Hsu’s horror-comedy Dead Talents Society transplants into the afterlife the triumphs and trials of the lonely—be they neglected young adults or fading stars. As a critique of success, meritocracy, and the craving for visibility, the film is as poignant as it is tongue-in-cheek, even if it falters in fully committing to its own argument.

In this world, the souls of the dead roam the earth until they are forgotten by their surviving loved ones, at which point they vanish altogether. Those most skilled at spooking the living become celebrities in the spiritual realm and, more importantly, earn a “haunting permit” granting them permanent existence. On the brink of being forgotten by her family, the unnamed young protagonist—dubbed “Rookie” by reviewers and played by Gingle Wang—attempts to secure a haunting permit before she disappears entirely. Painfully shy, Rookie’s stumbling pursuit of ghostly stardom leads her to Makoto (Bo-lin Chen), a talent scout with a soft spot for underdogs, who also represents the washed-up diva Catherine (Sandrinne Pinna).

This is a playful subversion of the horror genre; Hsu is more intent on delivering wry social commentary than on unsettling his audience. Here, ghosts are aspiring celebrities, and haunting demands stage presence and flamboyance: before her decline in popularity, Catherine appears on talk shows, smears black eyeliner on her face for the Golden Ghost Awards, and acts as spokeswoman for coveted “ghoul-exclusive” cosmetic brands. Hsu’s conceit—that the dead would likely invent their own entertainment industry out of nothing—allows him to satirise influencer culture: is there anything we are unwilling to commercialise and turn into a competition?

Yet beneath the comedy lies something more affecting, embodied in Rookie. Even in death, she is the archetypal jaded young woman, draped listlessly across her parents’ sofa. The apathy on her face begins to resemble misery once the details of her life emerge. Urged on by her father—“our only purpose in life is to stand out,” he tells her—Rookie has spent her short existence striving, and failing, to meet her family’s expectations. In her parents’ eyes, she is a spectacularly late bloomer; in her own, she is a failure, ignored by her community despite her efforts.

Much of Hsu’s critique strikes painfully close to home. The compulsion to stand out is universal, yet it feels especially acute in East Asian contexts. Amy Chua captures this pressure memorably in her 2011 memoir The Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, recalling how—during a relatively nurturing moment—she told her daughter before a performance: “Don’t blow this. Everything turns on your performance […] If you’re not over-the-top perfect we’ll have insulted [the spectators].” Even within a loving family, I have felt echoes of this; one older relative only met my gaze for the first time in years after I mentioned securing a prestigious internship. Rookie’s plight is thus deeply relatable—her lack of a given name underscoring her role as an Everywoman. The film, in this sense, voices the anxiety that the individual is condemned to live—and perhaps to remain in death—subject to the scrutiny of the public gaze.

Bound by their fear of vanishing, Catherine and Rookie find unexpected kinship. Rookie’s father, though soft-spoken and ostensibly encouraging, is no less intent on her excelling: before her untimely death, he cleared a place in the family cabinet, urging her to fill it with trophies, and drew constant comparisons with her overachieving sister. The suffocating pursuit of recognition can permeate even the most well-meaning of families. Meanwhile, Catherine, ousted from the limelight by younger talent, is equally desperate to maintain public attention. In Hsu’s vision, the education system and the entertainment industry converge upon the same truth: the human need for acknowledgement. By situating this struggle in the afterlife, Hsu intimates that the fear of fading into obscurity transcends death itself. The yearning to be remembered and cherished posthumously is but an extension of the forces that animate the cut-throat industries of the living.

The film offers, tentatively, a consoling resolution. After a failed confrontation with her rival, Catherine sits despondent until Makoto proposes that they haunt unsuspecting influencers for amusement. Catherine hesitates; what is the point of scaring people if no one is there to witness it? “I’ll watch you,” he replies, extending his hand, “even if there’s no one else around to watch.” In that moment, the act of watching becomes an act of love rather than appraisal. The film illuminates the capacity of the human gaze to nurture rather than to judge. Makoto, smitten, observes Catherine through a crack in the doorway with a mixture of awe and tenderness. When Rookie, crushed by her perceived mediocrity, collapses in tears in the street, Catherine crouches beside her, meets her gaze, and enfolds her in a wordless embrace—her eyes soft, her understanding complete. One who truly loves and values you will see you, not simply view you—and that, the film suggests, may be all one needs. The found-family trope here is both warming and liberating, offering a reprieve from the all-consuming imperative to perform.

But to what extent can the individual ever truly sever themselves from the need to be watched? Here, the film appears to write itself into a loop. Makoto, Catherine, and Rookie end up terrorising the influencers so effectively that they regain favour within the ghostly entertainment industry. It is through this inadvertent stunt that they are permitted to continue haunting the living world for a little while longer. In other words, they evade rejection only by managing—albeit accidentally—to conform once more to the very system they might wish to escape. Thus, when they are shown in the closing minutes sprawled in comfort in a hotel lounge, playing cards and discussing whom to scare next, one cannot help but sense the gaze of the masses lingering somewhere beyond the frame; their freedom carries with it a fragile, illusory quality. Paradoxically, liberation from the public gaze is attainable only through conformity to it.

Beneath Dead Talents Society lies the persistent anxiety that we may never fully extricate ourselves from the compulsion to remain hyper-visible. The film wishes to have it both ways: it wants to believe that all we require are loved ones who perceive us for who we truly are, yet it also clings to the fantasy that, one day, we will “make it” and be seen by all. That the film cannot offer a wholly satisfactory resolution to our ingrained fear of being forgotten does not render it any less enjoyable. Hsu’s ghosts are granted, for a brief time, the freedom to explore what being perceived actually means to them—and the same is true of us as we watch. All that remains is to enjoy the laughter, and perhaps to approach our own pursuit of recognition with a touch more self-awareness.

How to cite: Cho, Keziah. “Gazing at Ghosts: John Hsu’s Dead Talents Society.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 16 Aug. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/08/16/dead.

Keziah Cho is an English Literature graduate from University College London and will begin a Master’s degree in English at Cambridge University this October. Her poems have appeared in Voice and Verse, The Foundationalist, Crank Literary Magazine, Emerge Literary Journal, and Pi Magazine. As a student journalist, she has also published articles in Cha, Pi Media, The Cheese Grater, emagazine, and Empoword. When she is not writing, she is likely baking up a storm in her kitchen. [All contributions by Keziah Cho.]