📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

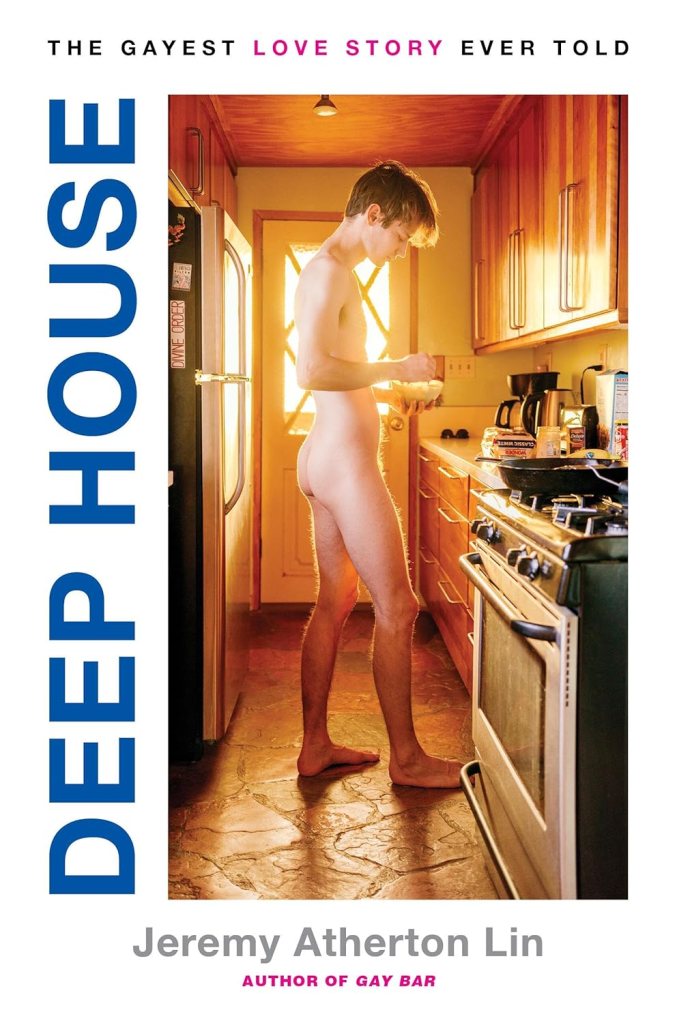

Jeremy Atherton Lin, Deep House: The Gayest Love Story Ever Told, Allen Lane, 2025.

Deep House, a memoir by Jeremy Atherton Lin, may or may not be “the gayest love story ever told”, as the book’s subtitle proclaims—as if there existed some metric for queerness and an omniscient survey of every love story in history. Reading it is akin to being invited into the most intimate spaces of Lin’s and his husband’s lives, into the various homes they have inhabited, owing to the author’s generous candour. “Deep house” is, of course, widely recognised as a subgenre of music. Read in musical terms, the memoir achieves the perfect composition: the steady pulse of house, the jagged chords of jazz-punk, and the warm undertones of soul. It is rhythmic, edgy, fast-paced, free-flowing, and restorative to the spirit—suffused with creative energy, unrestrained freedom, and virtuoso storytelling.

The 400-page volume—including more than thirty pages of endnotes testifying to the depth of research underpinning the work—is narrated in the first person yet addressed throughout to “you”: the author’s boyfriend, now husband, Jamie. It is, in essence, a love letter. The consistent use of the second person is a notoriously difficult technique to sustain, yet Lin executes it with remarkable poise. The writing never lapses into dullness or overbearing didacticism. Deep House is memoir at its finest—artfully fusing the personal chronicle of a queer relationship with the social history of LGBTQIA+ struggles for rights and acceptance across the Atlantic over the last three decades.

At its heart lies the love story between the narrator (“Jeremy” or “I”), a California-born Chinese American, and his partner (“Jamie” or “you”), an adventurous British artist. The narrative opens with their first meeting in London in 1996 (an event also recounted in Lin’s first book, Gay Bar, another superlative work of nonfiction), at a time when the US Congress was preparing the Defence of Marriage Act, thereby denying same-sex couples rights including immigration. It concludes with the couple’s eventual settlement in the United Kingdom, having migrated from the United States, and the conversion of their civil partnership into a marriage certificate in 2016—by which time both countries had legalised same-sex marriage. Between these bookends stretch two decades of love, border-crossing, and homemaking, set against the global backdrop of queer activism for marriage equality and social justice since the 1990s. Lin’s personal history is woven seamlessly into the wider social fabric, illustrating with precision the indivisibility of the personal and the political.

In Deep House, being queer in a heteronormative world is likened to living as a migrant in a foreign country, or as a tenant in a residential neighbourhood. The San Francisco district where the couple last resided in the United States projected the image of a cheerful, welcoming community—until Lin arrived at a sobering realisation: “The locals welcomed you and me into the fold. But it was their home, whereas you and I, even after all that time, we were just tenants […] I suppose that’s community. But we were only renting” (p. 335). It is a sharp indictment of the façade of American multiculturalism and of the private property-based social relations underpinning neoliberal capitalism.

Towards the close of the book, Lin reflects: “Our case, it turns out, has never really been marriage, but borders” (p. 359). This line encapsulates the couple’s arduous experiences of living together as a binational couple—at one point, one partner was compelled to become an “illegal immigrant” simply so they could remain together. It also offers a vital queer migrant’s perspective on the “same-sex marriage” debate within the LGBTQIA+ community: the right to marry a partner of the same sex is not necessarily about acquiring privileges once reserved for heterosexual couples—it is equally about securing basic human rights, including the right to live together without fear of discrimination, detention, or deportation. Responding to the young Gay Shame protesters who rallied against same-sex marriage, Lin confesses: “We were ashamed we couldn’t take that position. We were too desperate. Nor could we campaign for same-sex marriage for risk of exposure. Anyway, although I didn’t know anyone who would have benefited more from accessing the same rights as a straight married couple, it never felt like our cause. I’d always thought any cause worth fighting for must be about someone else” (p. 291).

Lin’s prose is at once humorous, elegant, and intelligent. Queer domestic life in a rented flat—with two men and two cats—despite the illegality of the couple’s immigration status, the unrecognised legal standing of same-sex relationships, and the precarity of tenancy, becomes both poetic and philosophical: “Everyone in the room fell into the same rhythmic breathing. You could see the heaving of their breath clearly, especially with Clementine [the name of a cat] in the middle. We adapted to their feline way of perceiving. They required no paperwork from us. We were real to them. We were, at least, all breathing. The rise and fall of cat bellies, calming but vulnerable, two more bodies woven into a never-quite-settled life, becoming atmosphere” (p. 319). This quiet reflection on the convivial relationship between human and non-human worlds speaks volumes against both humanity’s domination of the non-human and the state’s regulation of bodies and borders.

The cover and epigraph of Deep House invite the reader into an act of voyeurism—peering into the intimate spaces of others’ lives. One is left with the profound sense that the book is, in truth, about all of us: how we—as individuals, societies, and nations—perceive and treat the sexual, the national, and the racial “other”; how our most private lives are governed by state laws, national frontiers, and social mores; and how we might either escape—or dwell within—the loopholes of these regulatory regimes. An inspiring and deeply affecting read.

How to cite: Bao, Hongwei. “On Queerness, Migration and Same-Sex Marriage—A Review of Jeremy Atherton Lin’s Deep House: The Gayest Love Story Ever Told.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 13 Aug. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/08/13/deep-house.

Hongwei Bao is a queer Chinese writer, translator and academic based in Nottingham, UK. He is the author of Queer China: Lesbian and Gay Literature and Visual Culture under Postsocialism (Routledge, 2020) and Queering the Asian Diaspora (Sage, 2025) and co-editor of Queer Literature in the Sinosphere (Bloomsbury, 2024). His poetry books include The Passion of the Rabbit God (Valley Press, 2024) and Dream of the Orchid Pavilion (Big White Shed, 2024). [All contributions by Hongwei Bao.]