茶 FIRST IMPRESSIONS

茶 REVIEW OF BOOKS & FILMS

[ESSAY] “As If Present; As If Absent: Fang Fang’s Wuhan” by Angus Stewart

Click HERE to read all entries in Cha on Fang Fang.

Editor’s note: In this eloquent and incisive essay, Angus Stewart reflects on four works by Fang Fang in English translation. Moving beyond the controversies surrounding her celebrated diary, Stewart explores the author’s sustained engagement with record-keeping, memory, and societal amnesia, set against the fraught landscape of modern Chinese history. His reading reveals the subtle interplay between realism and the literary, and situates Fang Fang firmly as a writer of enduring moral and artistic significance. Books discussed in this essay: Fang Fang’s Wuhan Diary (trans. Michael Berry, Harper Collins, 2020), The Walls of Wuchang (trans. Olivia Milburn Sinoist Books, 2022), The Running Flame (trans. Michael Berry, Columbia University Press, 2025), and Soft Burial (trans. Michael Berry, Columbia University Press, 2025).

In the fiction and nonfiction

of Fang Fang’s Wuhan,

there’s no conscience without memory.

I ran The Translated Chinese Fiction Podcast from 2019 to 2024, yet never read Fang Fang’s Wuhan Diary when it was making the news. The recent publication of Michael Berry’s translations of two further works by Fang Fang drew my attention back to her, prompting me to read Wuhan Diary alongside those two new titles and another relatively recent one. I found that the motif of record-keeping ran through all these works, intertwined with themes of social conscience and societal amnesia. My essay examines these concerns, engaging both with the tangible challenges of recent Chinese history and the more abstract question of how the past can, in fact, be accessed—if at all. To be even more blunt about my aim, I wish to offer readers a sense of Fang Fang as a literary author, and to consider where that literary sensibility emerges within her celebrated diary.

◍

When reading modern Chinese writers in translation, selecting from only a fraction of their bibliographies is the norm. The available texts tend to be those deemed most worthy—whether for their social significance or their market potential. Fang Fang presents an intriguing case. Over the decades, she has become something of a laureate for her native Wuhan, firmly embedded within China’s state writers’ system. In that time, she has accumulated numerous domestic awards and deployed her plain-speaking realism to illuminate social issues that would appeal greatly to the cohort of Western readers eager for critical perspectives on life in the PRC.

Until 2020, however, one would have had to search with some determination to locate any of Fang Fang’s work in English translation. Then COVID-19 arrived.

As Wuhan became the first city in the world to enter lockdown, Fang Fang began composing and posting a daily record of her thoughts and experiences. This online diary swiftly attracted a substantial readership, but it also provoked controversy for its pointed remarks about officialdom’s initial response to the outbreak. Criticism of the author intensified into a full-blown pile-on after she sold foreign-language translation rights. HarperCollins acquired the English edition, and thus—for ‘China watchers’—Fang Fang’s account of lockdown (and the abuse and accusations she endured) became the flavour of the month.

Online drama, like criticism, is irresistible. But what else is on offer? Five years on, I have taken the time to gather and read the four Fang Fang books readily available in English translation. (Other, more obscure titles exist—but I cannot vouch for them.) My four are as follows…

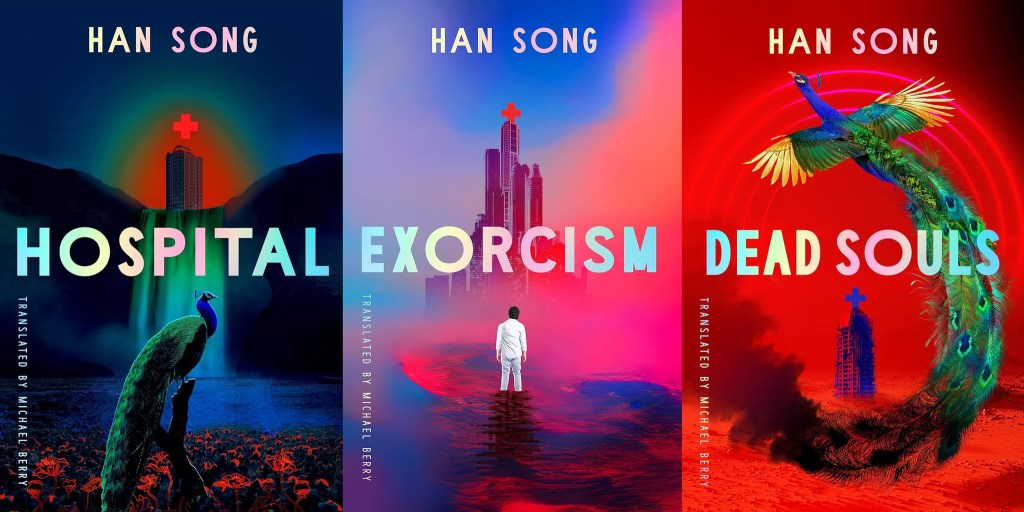

Published first was Wuhan Diary—non-fiction, and already introduced. Its translator is Michael Berry of UCLA, who has also recently been credited with translating Han Song’s Hospital trilogy.

Han Song’s Hospital trilogy, trans. Michael Berry

Next comes The Walls of Wuchang, a work of historical fiction published in 2011, which recounts the 1926 siege of one of the three cities comprising present-day Wuhan. The English translation was quietly released in 2022 by Sinoist Books. One might reasonably infer that its parallels with the lockdown in Wuhan informed this low-profile publication. The translator is Olivia Milburn, a regular contributor to Sinoist’s list.

The most recent translations are The Running Flame and Soft Burial, both issued by Columbia University Press and translated by the aforementioned Michael Berry. The former, a novella originally published in 2001, tells the story of a rural woman imprisoned for turning on her abusive husband. The latter is the most substantial and ambitious of the four works under consideration, exploring buried trauma from the Chinese revolution’s overthrow of rural landlords, recounted through the gradually revealed origins of a woman who washes up on a riverbank without memories. First published in 2016, it courted controversy almost as swiftly as it garnered acclaim.

In reading these four books consecutively, I found that questions of public and personal memory, amnesia, and record-keeping are not confined to Soft Burial and Wuhan Diary—they are, in fact, woven inextricably through all four. Fang Fang makes no direct demands upon our sense of duty or morality—she is far too down-to-earth for that—but across these works, the implicit imperative to record and to remember is impossible to ignore.

◍

It felt right—and still feels right—to begin with The Running Flame. The work stems from an interview Fang Fang conducted for the television programme Thirteen Murders. Episodes five and six of the series cover the real-life case that inspired The Running Flame: a villager named Yingzhi is subjected to ever-worsening abuse by her husband and in-laws. Yingzhi’s eventual imprisonment frames the novella. At its opening, she resolves to recount everything to her cellmate. “Let me start over again,” she says, and we are told that she is weeping as she begins. Thus, there is no diary or written record in The Running Flame, but rather a thread of oral history—one among countless instances of the familial oppression of women in rural China. This oppression may have been alleviated by a century of revolution and reform, yet it remains far from eradicated.

There is a temptation to leap straight to Soft Burial here, but I shall resist it. I prefer to linger a little longer with this shorter, older novella, to hazard a comparison with other translated Chinese works I might, with some nerve, call ‘punk’. I am thinking of works that scratch several of the following itches: moral ambiguity, misdeeds in the backwaters, a rapid-fire plot, off-the-books economics, a touch of sex, a hint of crudity, a measure of drink and gambling, and a general disinterest in grand critiques or sweeping historical vistas. In short—a touch of sin.

Yingzhi is no icon. She does not strike one as especially intelligent, emotionally mature, or morally enlightened. The novel does not see her launching a feminist uprising, nor orchestrating a prison break, nor building a business empire. Social realist fiction endures because honesty wounds—and because the working class and rural poor, whom soft-skinned urbanites might find unpalatable, deserve neither more nor less pity in their suffering than the liberal, the cultivated, or the genteel. The impossibility of Yingzhi’s circumstances, and the retrograde mentality of her tormentors, are the crux of The Running Flame: control and cruelty form part of the historical record.

In the city, in a marginally better life, Yingzhi might have lived on her own terms—an edgy Shanghai Baby, perhaps, or a hooligan Running Through Beijing—but not everyone is destined for the metropolis, and “better” presupposes “worse”.

◍

Is Wuhan Diary punk? Yes and no. The format has a certain flippancy—all acclaim aside, it is a sequence of posts written for the internet, corralled between covers. Yet the tone, when critical, is grounded in common sense and conscience. It begins as a personal record, written and shared seemingly for the sake of the author’s sanity, but as the entries progress and she feels the heat from her detractors, she doubles down—turning her writing into an indictment of the bureaucrats, refusing to back down from demanding answers on the failings of Wuhan’s initial response to the outbreak. Five years on, readers like myself encounter the Diary not as a news item, but as a record. It is emotional, political, and also steeped in the mundane.

Read it, and you will learn about Fang Fang’s dog, her daughter, and her diabetes. To some extent, the Diary offers a zoomed-in chronicle of lockdown life within the Literary and Arts Federation compound, where Fang Fang resides alongside many of Wuhan’s other writers and artists.

Having lived through the United Kingdom’s own pandemic response, I found it compelling to ‘see’ quarantine in China through the eyes of one of the country’s literary elite. And it is worth remembering—she writes only during that first lockdown; she does not know what is to come, either at home or abroad. It was an uncanny time… as you will recall, wherever you were.

◍

And yet The Walls of Wuchang does not feel like an eerie premonition of Wuhan Diary. In the latter, Fang Fang herself remarks on the siege–lockdown synchronicity, but her only analysis is an ironic dig—that the rival military forces in Walls prove more adept at compromise in the face of crisis than Wuhan’s twenty-first-century authorities. One might also draw a link concerning the absence or provision of food, but it remains tenuous.

The power of Walls as a historical record—a work of anti-amnesia—did not strike me fully until the end matter. There, in Fang Fang’s afterword, she writes that she had never known of any wall around the city until a classmate and a historian showed her some of its last remnants—bricks repurposed as part of the residence of Shi Ying, an early twentieth-century revolutionary. This discovery prompted her to investigate the history of their destruction—an outcome of a sequence of battles during the Northern Expedition, when a northbound Nationalist army pursued forces under the command of warlord Wu Peifu into Wuchang and trapped them there.

The novel is divided into two parallel halves: “Attacking the Walls” and “Defending the Walls”. “Attacking” follows a handful of young Nationalist soldiers through to their bittersweet victory; “Defending” then rewinds to focus on various civilians (and one defending officer) trapped inside the city. In her afterword, Fang Fang openly concedes that the novel is not intended as a flawless reconstruction of historical events, noting that even the non-fictional records are hazy on certain dates. Nevertheless, she includes various non-fictional appendices, among them a list of fallen combatants which she emphasises is woefully incomplete.

In the final verso and recto of “Attacking”, years after the fighting has moved north, Fang Fang has a monk visit the city in search of a tomb that may house the remains of certain characters who did not survive the siege. He makes enquiries, but no one can help him. The record is lost. Here the tone shifts—from Fang Fang’s usual directness to something meditative, almost delicate. It is a beautiful passage, and I shall not spoil its magic with a quotation, but I will note that, upon reflecting on his failure, the monk writes the line I have borrowed for the title of this article.

◍

The mystery of where past events exist, if not in record, is a melancholic and intractable question. The plain, realist prose with which Fang Fang made her name cannot resolve it. Realism will not suffice, however great the commitment to research and reportage one brings to the task. It is little wonder, then, that in Soft Burial we see Fang Fang adopting a more overtly literary approach. The first paragraph is a single sentence: ‘She is someone in a state of constant inner struggle.’ The paragraphs that follow sketch the physical appearance and habits of an elderly woman, teetering on the edge of senility. Over the course of this comparatively long novel, we come to learn of the great rupture that ended this woman’s early life—memories either damaged or repressed—her experience on the receiving end of the Land Reform Movement.

The event that triggers the excavation of these memories is based on a real account, twice removed from Fang Fang herself. In her afterword she recounts the occasion: a friend’s mother, ushered by relatives into a newly built mansion acquired through post-Mao prosperity, was seized by a sudden and inexplicable dread. Her past privilege had long since vanished, but the punishment and exile meted out to her for it had taken up a permanent, intangible residence within her. In Soft Burial, Fang Fang makes the move—simultaneously subtle and direct—to treat this mother’s personal amnesia as a metaphor for a broader national and societal amnesia.

China’s twentieth century offers no shortage of horrors: colonisations, invasions, famines, civil wars, self-inflicted wounds, and political persecutions. Perpetrators, both foreign and domestic, abound, and the question of who may be so named is itself incendiary. Perhaps it is unsurprising, then, that the overturning of the landed gentry has yet to secure a place within the already crowded, politically freighted ‘canon’ of trauma. Many might contend that some form of overturning was necessary, and the fact of a communist revolution is hardly a state secret. But the dark core of Soft Burial breaches a cache of the Land Reform Movement’s excluded memories—one local case of ground-level inhumanity in the form it took. We might well ask how shallow lies the grave.

Discussions of collective amnesia in the PRC that I have encountered generally frame it as enforced—a top-down policy of erasure by the Communist Party. The example most often cited is 1989 in Tiananmen Square; blocked websites and banned vigils attest that the policy endures. Yet Soft Burial reminds us that reality—or the grave—runs deeper.

The novel concludes by suggesting a different kind of choice, one in which the decision to record, remember, and investigate, or to forget and move on, lies with the traumatised and their descendants. One character chooses to respect his parents’ wishes and relinquish the burden, to spare his children the inheritance of pain, resentment, and suffering. Another feels it his duty to learn more—to turn his back on success in the city, return to the remote backwaters, and exhume whatever remains. And the choice is only possible, in large part, because of a secret record left for posterity: writing on paper that has outlived its author. A diary. Is that not interesting?

How to cite: Stewart, Angus. “As If Present; As If Absent: Fang Fang’s Wuhan.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal 12 Aug. 2025. chajournal.com/2025/08/12/Fang-Fang.

Angus Stewart is a Dundonian living in Greater Manchester who writes occasional strange stories and essays. His works have appeared in various small publications including Ab Terra, STAT and Dark Horses. His show, the Translated Chinese Fiction Podcast, is on hiatus. [All contributions by Angus Stewart.]