📁RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

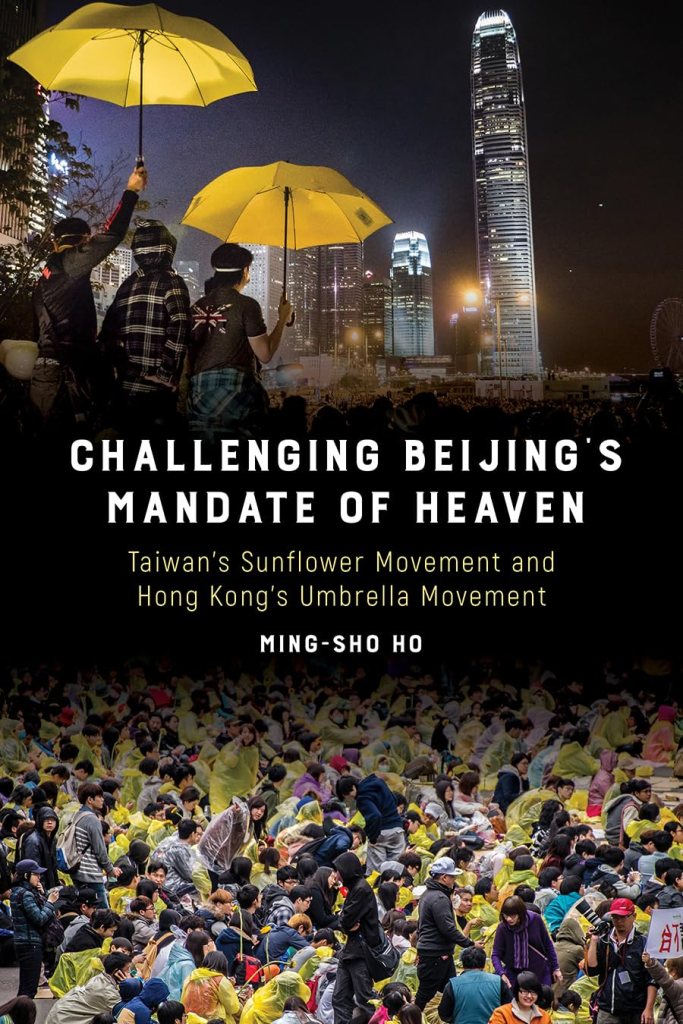

Ming-sho Ho, Challenging Beijing’s Mandate of Heaven: Taiwan’s Sunflower Movement and Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement, Temple University Press, 2018. 270 pgs.

Ming-sho Ho’s Challenging Beijing’s Mandate of Heaven compares the origins, processes, and outcomes of Taiwan’s Sunflower and Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movements, noting key similarities and differences by examining their evolution, modes of mobilisation, and eventual outcomes—both domestically and internationally.

As in his later work, Be Water: Collective Improvisation in Hong Kong’s Anti-Extradition Protests (2025), which I recently reviewed for Cha, Ho draws on a wealth of materials—including published works, films, social media, speeches, art, and, in particular, his own in-depth interviews—offering robust triangulation of data. The book begins with a personal anecdote to “set the scene”, grounding the movements on a personal level, and outlines its more specific methodology in an appendix. One senses that the author is developing a framework by which other mass and relatively long-lasting protest movements might be analysed in a similar fashion—thereby advancing the broader study of social movements.

Both movements shared characteristics of “unanticipated emergence” (though I would argue that the signs of political action were always present), were large in scale, involved intense and widespread popular participation, and had “deep and far-reaching consequences”—all while challenging Beijing’s “mandate of heaven”. “Spatial factors” were also significant, with protest actions occupying specific areas.

Ho identifies six “intellectual puzzles” that serve as the foundation of his comparative analysis, potentially illuminating the inception, trajectory, and outcomes of the two movements—despite constraints that might have limited their effectiveness:

- Radicalism in conservative societies—where social harmony and consensus were traditionally prized, though this might be contested, particularly in the case of Hong Kong, often labelled “politically apathetic” in the past;

. - “Hopeless” protests?—why protest actions continued despite dim prospects of success, perhaps due to the broader implications of the “China factor”, including trade relations;

. - Student leadership—the apparent side-lining of the “old guard”, possibly due to the inability of NGOs, political parties, and other organisations to effect meaningful change;

. - The curse of movement resources—Hong Kong students appeared to have better-prepared resources but were ultimately unsuccessful, whereas the comparatively under-resourced Taiwanese protestors saw more tangible success;

. - The source of unsolicited contributions—how both Taiwanese and Hongkongers managed to sustain such orderly and prolonged protests with seemingly decentralised leadership;

. - Solidarity and schism—the Umbrella Movement’s conclusion led to fragmentation within Hong Kong’s opposition, while the Sunflower Movement enabled Taiwan’s opposition party to secure electoral victory.

These six “puzzles” form a coherent narrative thread throughout the book, facilitating a clear and engaging comparative analysis. While it is difficult to do justice to each puzzle here, readers familiar with the Hong Kong case should find them accessible and illuminating.

China’s impact on the two societies is addressed in Chapter 2—specifically in relation to the rejection of economic integration with China and the growing power of the mainland. Ho argues that this has reinforced local identities in both contexts. Both movements constituted challenges to Beijing’s imperialistic political project to bring the two societies under firmer control—and thus to its “mandate of heaven”.

Chapter 3 examines the “forging of movement networks” by analysing the linkages between various social movement actors (e.g., students, NGOs, and opposition parties) and the pre-existing activism in both societies. This chapter also contends that there was a “generational youth revolt” among those born in the late 1980s—evident in pre-Umbrella Hong Kong and pre-Sunflower Taiwan—largely stemming from economic deprivation in the new millennium. However, I would not regard this simply as a reaction to economic downturn, but rather as a consequence of the development of more localised identities in each place, the weakening of emotional ties to mainland China, and an emerging desire for greater agency in determining the political conditions of their lives.

Chapters 4 and 5 provide detailed accounts of the sequence of events in both the Sunflower and Umbrella Movements through the framework of “opportunities, threat and standoff” (p. 148). The analysis in these chapters reflects on the sustainability of mass movements in spite of unprepared leadership and limited resources for the continuation of political action. This leads to the author’s concept of “improvision”, which becomes the focus of Chapter 6.

“Improvisation” may also be understood as the “personalisation of contentious politics” and the mobilisation of the broader public. Ho identifies five types of improvision: (1) maintaining a logistics supply; (2) encouraging strength and participation; (3) sustaining morale; (4) presenting a favourable public image; and (5) relaunching offensives when momentum flagged.

From my close observation of the Umbrella Movement, it is clear that these were critical to the movement’s sustainability, particularly through the widespread volunteerism of the public—manifested in both so-called “rational” and “radical” forms. These improvisions were replicated, adapted, or innovated as circumstances evolved. However, limitations to improvision also existed. This does not suggest that the movements were leaderless—rather, they exhibited a flexible form of leadership. This is particularly interesting in light of the 2019 Hong Kong anti-extradition protests, often described as “leaderless”, yet in reality characterised by a kind of “floating” leadership, in which “seasoned activists” were better positioned to assume executive roles.

Chapter 7 concludes with an examination of post-Sunflower and post-Umbrella developments, focusing on the shift from activism to electoral politics. Although many perceive the Hong Kong case as a “failure”, I do not share this view—it catalysed greater political mobilisation. In Hong Kong’s case, it led to the emergence of “localism”, a reduced emphasis on change in the mainland, and the rise of more radical, predominantly youth-led groups, whose political ascendancy came at the expense of the pre-existing opposition.

In Ho’s account, the Umbrella Movement unfolded under conditions in which social movement and NGO actors were comparatively better resourced and more prepared. Nonetheless, the eventual outcome was perceived as less successful than in Taiwan. This, Ho argues, may be attributed to a variety of factors, including stronger trust among Sunflower Movement student activists, NGOs, and political parties, as well as the greater experience of many Sunflower activists compared to the often younger participants in Hong Kong.

Challenging Beijing’s Mandate of Heaven offers a substantial overview of Taiwan’s Sunflower Movement (about which I was largely unfamiliar and thus cannot critically assess its accuracy) and Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement (with which I am very familiar), bringing both into a single, comprehensive volume. Despite its academic nature, the text presents its comparative analysis in a lucid and accessible manner. In sum, this is a significant contribution to the scholarship on social movements in East Asia.

“Democracy Road”, photograph © Jennifer Anne Eagleton

“It’s just the beginning”, photograph © Jennifer Anne Eagleton

How to cite: Eagleton, Jennifer. “Radicals, Realists, and Revolutions—A Tale of Two Movements: Ming-sho Ho’s Challenging Beijing’s Mandate of Heaven.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 6 Aug. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/08/06/sunflower.

Jennifer Eagleton, a Hong Kong resident since October 1997, is a close observer of Hong Kong society and politics. Jennifer has written for Hong Kong Free Press, Mekong Review, and Education about Asia. Her first book is Discursive Change in Hong Kong (Rowman & Littlefield, 2022) and she is currently writing another book on Hong Kong political discourse for Palgrave MacMillan. Her poetry has appeared in Voice & Verse Poetry Magazine, People, Pandemic & ####### (Verve Poetry Press, 2020), and Making Space: A Collection of Writing and Art (Cart Noodles Press, 2023). A past president of the Hong Kong Women in Publishing Society, Jennifer teaches and researches part-time at a number of universities in Hong Kong. Her latest book is Hong Kong’s Second Return to China: A Critical Discourse Study of the National Security Law and its Aftermath (Palgrave, 2025). [All contributions by Jennifer Eagleton.]