📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

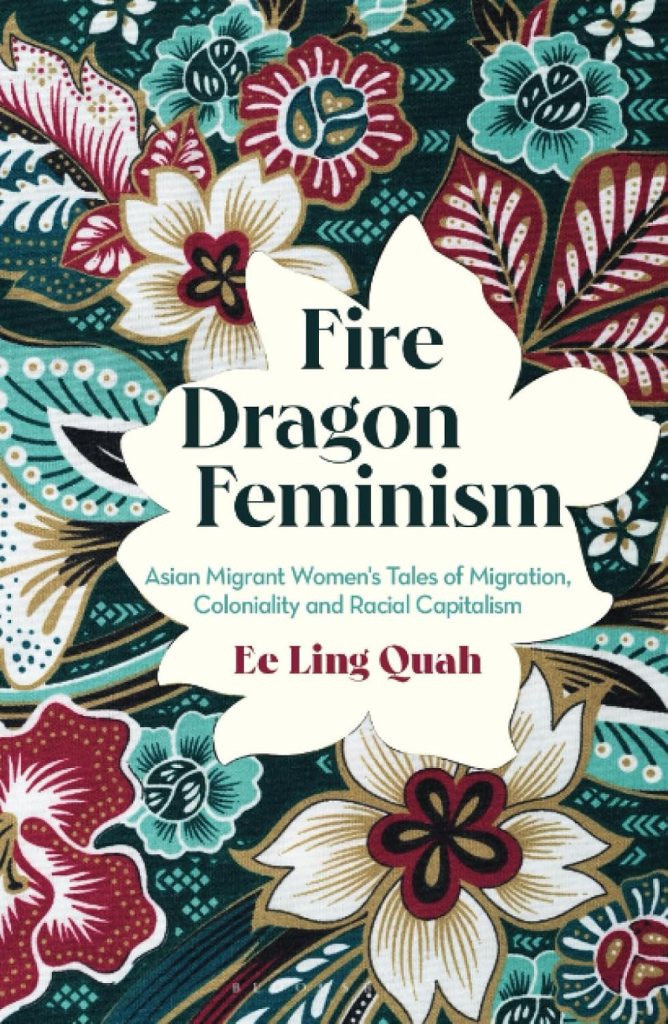

Ee Ling Quah, Fire Dragon Feminism: Asian Migrant Women’s Tales of Migration, Coloniality and Racial Capitalism, Bloomsbury, 2025. 216 pgs.

“An exchange of glances, light nods and eye contacts across the room with another person of colour who is just as agitated by that racist comment, question or suggestion at a staff meeting is enough to validate every fibre of our collective racialized beings and send a booster shot of energy in hope to sustain us till the next destabilising and dehumanising racialised episode.” (p. 168)

Ee Ling Quah’s Fire Dragon Feminism is a powerful, poignant manifesto—at once a searing critique and a therapeutic embrace from a sister who reassures migrant Asian women working in Eurocentric parts of the world: “I understand you. And you are not overthinking.”

While there is extensive literature on the racialised experiences of Asian Americans—such as Cathy Park Hong’s Minor Feelings: A Reckoning on Race and the Asian Condition and Anne Anlin Cheng’s Ornamentalism—Quah notes a dearth of writing on the experiences of migrant Asian women in the Asia-Pacific and post-settler colonies. This observation, together with her own experiences as an Asian, queer, woman academic in Australia, fuelled the writing of Fire Dragon Feminism.

Through interviews with migrant Asian women—like herself—working in higher education in Australia, Quah deconstructs the colonial structures and enduring legacies that shape the quotidian, racialised encounters faced by these women. Mindful of binaries and the reductive framing of these encounters solely in terms of victimhood, Quah also examines lateral forms of racialisation that occur within the group itself. As she writes in her book:

“It just shows how the system works to actually perpetuate this kind of whiteness as the norm…where we suffer racism from non-white people, and sometimes people from your own.” (p. 110)

It is this determination to capture complex relational dynamics that renders Quah’s account both powerfully and emotionally authentic.

In the first part of her book, Quah recounts the stories behind her conceptualisation of fire dragon feminism. The phrase fire dragon is steeped in folklore and urban myth, shaping racial constructs and stereotypes of Asian women—both within Asia and beyond. These constructs are antithetical and wide-ranging: from the extraordinary woman warrior, the Little Dragon Maiden, in the Chinese martial arts novel The Return of the Condor Heroes, to the derogatory associations in Southeast Asia of Little Dragon Women as sex workers from Mainland China engaged in illicit trade, or as grasping, materialistic figures.

The assemblage of myths surrounding the Dragon Lady is also influenced by Chinese cosmology, which holds that those born in the Year of the Dragon and under the element of fire possess the most auspicious and fortunate destinies. This belief precipitated a baby boom in 1976—the Year of the Fire Dragon—and, consequently, intensified competition for resources and opportunities. As Quah observes, these life chances are further constrained by prevailing systems of race, heteronormativity, patriarchy and body ableism.

It is precisely these myths that she seeks to confront through fire dragon feminism. To quote Quah:

“The framework seeks to understand how Asian migrant women’s lives are shaped under the influence and impact of this corpus of racialised, sexualized and ethno-cultural myths. Fire dragon feminism is interested in collecting the women’s stories of how they break free of these myths, queer power structures imposed on them and carve out their trailblazing path for collective survival and sustainability.” (p. 42)

In the remainder of her book, Quah reflects on her own experiences alongside those of the women she interviewed. She offers several astute critiques with which I deeply resonate—particularly her observations on the tokenistic gestures that now characterise many approaches to intersectionality and Equity, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) initiatives. While these efforts may stem from a genuine desire to foster inclusion and diversity, their implementation often amounts to little more than the recruitment of individuals from varied identities—across race, sexual orientation and bodily difference—or to the performative celebration of cultural festivals.

Rather than adopting an intersectional approach that acknowledges colonial histories and the power structures underpinning inequality, Quah persuasively argues that concepts such as intersectionality and EDI have been corporatised and co-opted to sustain colonial, white supremacist legacies. Both Quah and the women she interviewed recount instances in which inclusion and equity are ostensibly promised, yet when they speak out against racism and white supremacy, they are met with backlash and consequence.

As I read excerpts from the interviews in Chapters 3 and 4, I could only imagine how profoundly reassuring and therapeutic the process must have been for the participants. These women recalled experiences of racial discrimination and dehumanisation—ranging from the overt and incisive to the seemingly innocuous gesture that nonetheless left them feeling disrespected and uneasy. As Quah notes, almost all began their accounts with the phrase, “I don’t know if this is racism”, revealing their uncertainty over whether a given encounter qualified as racist or belittling.

To find a community of shared experience—to tell one’s story and be reassured that one is neither overreacting nor overly sensitive—is a liberating reprieve from the mental solitude and emotional distress these women have long endured.

The discussions were not solely concerned with racialised encounters, but also with the internalisation of these constructs. Many of the women spoke of the damaging and emotionally taxing labour of self-surveillance and self-critique in their efforts to conform to whiteness, as they—often unconsciously—sought to embody the roles and racialised stereotypes imposed upon them. There were numerous poignant moments in the book, but one particular quote struck a deep chord of resonance within me:

“Oftentimes, there is an assumption and expectation that minority people and communities bound by marginalisations, albeit difference in intersectional forms and manifestations, would be in solidarity and have one another’s back. Some of the respondents in this study explained that this was not always the case…. They shared that the shock to their bodily systems was oftentimes more pronounced when they experienced racialized violence from people of colour than when they encountered racism by white powers.” (p. 111)

It is heart-wrenching to read this—a stark reminder that, perhaps as a result of vicious competition, minority individuals may choose to gatekeep whiteness and replicate the very racialised violences they themselves have endured, sometimes with even greater aggression. These forms of lateral violence do exist, and are far more prevalent than one might imagine—yet they remain largely unspoken. I deeply appreciated the way Quah brings this reality to light and articulates it with nuance and judicious care.

We are both subject to—and, often inculpably, complicit in—the reproduction of global racial capitalism and the entrenched hierarchies of nations and citizenships.

Quah concludes her book with grace, introducing other migrant Asian feminist activists and their projects, including poetry. This conclusion is at once thoughtful and poetic, as she joins a collective of fearless feminist voices advocating for more sustainable and just futures.

I would like to close this review by returning to the quote with which I began: to be seen is an understated yet profoundly powerful feeling—and this brilliantly written book accomplishes precisely that. From the tokenistic practices of diversity and inclusion, to the emotional labour of navigating everyday power asymmetries rooted in colonial legacies and racialised structures, Quah addresses them all. This is a vital work—whether for migrant Asian women seeking understanding, or for those wishing to interrogate the structures of whiteness embedded in their EDI programmes.

To end, a line from a poem by Israa Merhi, a poet and feminist activist featured in the book:

“You are unique in so many more ways than a human could ever describe. Remember, you are a precious thing.” (p. 177)

How to cite: Chan, Loritta. “Decorative Roles and Dehumanising Gazes: Reflections on Ee Ling Quah’s Fire Dragon Feminism.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 6 Aug. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/08/06/fire-dragon.

Loritta Chan is a Lecturer at the National University of Singapore, with research interests situated at the intersections of children and young people’s livelihoods, waste ecologies, and sustainable urban environments. She received her PhD in Human Geography from the University of Edinburgh, where her dissertation examined the everyday lives and spatial practices of children and youth from waste-picker families in Delhi. In the intervening years, she undertook postdoctoral fellowships in the United Kingdom and Hong Kong, contributing to projects on inclusive urbanism for young people and on the social dimensions of water conservation. Beyond the academy, Loritta is an avid illustrator, a reader of poetry, and a committed pedestrian. [All contributions by Loritta Chan.]