📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

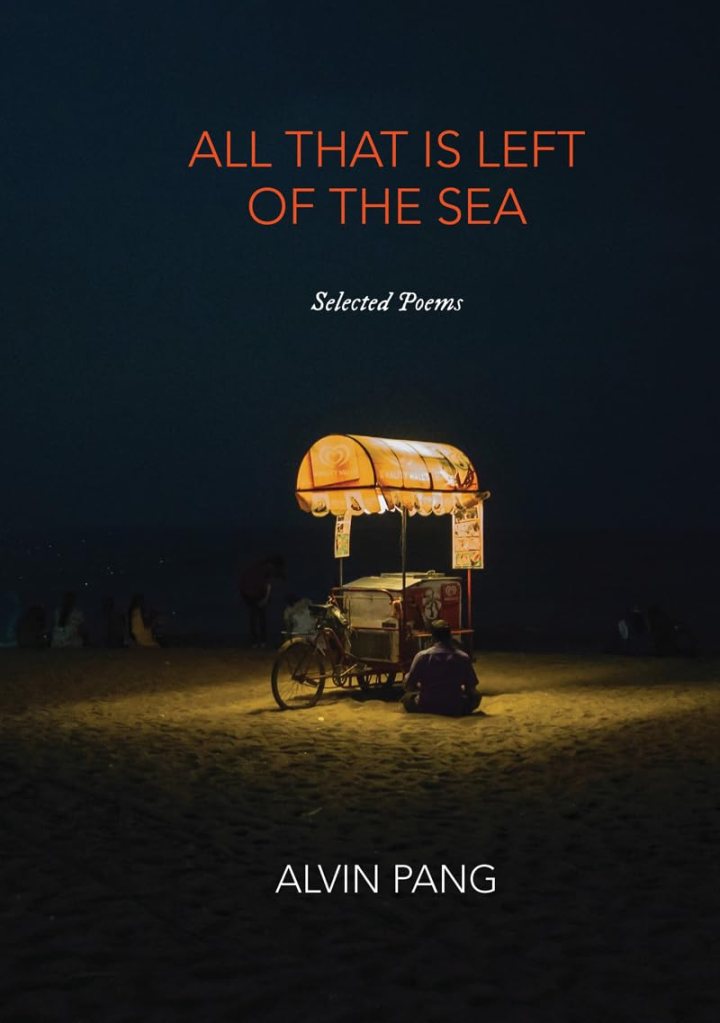

Alvin Pang, All That is Left of the Sea: Selected Poems, Red River Press, 2025. 148 pgs.

Emotions and poetry often operate by falling into sync with one another. But is it solely emotion that draws us towards good poetry? The answer may lean towards both yes and no. When it comes to distilling the perfect emotions into a compact set of stanzas, the poet must adopt a certain rigour towards their work, as it represents their true self and potential. It is no crime to cut one’s favourite lines from a poem—for those lines remain tethered to the artist. They may well extend themselves into another work, finding new form and future expression.

Alvin Pang’s collection All That is Left of the Sea: Selected Poems honours both the craftsmanship of poetry and the emotional resonance, elemental precision, and essence we seek in verse. It is like a cloud that rains with purpose—without eroding what lies in its path. It is a window that adjusts itself to offer us a clearer view.

“Strange Fish” is one such poem that captures both poetic craft and the necessity of freedom of speech. The poem breaks with grace, forming compartments for each utterance within the stanzas. Even the continuations carry distinct voices. It is no easy task to assemble such voices without creating disorder—at least not somewhere, if not everywhere. Pang, however, maintains a disciplined focus on how words are released. He does not drift aimlessly into the abyss in search of meaning, nor does he overwhelm the reader with all that language might evoke. It may now appear a manageable feat—but we must acknowledge that condensing an expansive idea into a single atomic sub-particle has always been an immense challenge.

Their small bodies

twist into commas

and pause at the surface,

dumb as alien

symbols. I hoist them

onto dry ground

with the rod of a pen…

Pang offers a personal and tender reflection in his poem Friction, where intimacy is rendered in its most organic form. The strength of the bond between him and his grandmother becomes evident in his vivid depiction of her bruised skin—how a syringe passes through it and dips into the blueness of her veins. When a poet observes with such precision and is able to write about the anatomy of a loved one, the emotion must be extracted with equal care and depth.

Here, the simple act of the poet rubbing her wrists triggers a sensation in her brain—conveying the closeness they share. The poem does not succumb to melancholy. Rather, it maintains a delicate equilibrium between what must be said and what might otherwise descend into melodrama. It invites emotion without indulging in it.

I imagine her

gaunt cheeks, soft hollow

fill and breathe with colour,

her eyes catching fire

as I rub at her wrists

for the heat of friction.

Most of us long for a small space of our own within this vast world—a space in which we might contain all the pleasures typically found only in the outer hemisphere. This desire represents an evolutionary progression, as the human mind begins to adapt to the solitude it occasionally craves. Alvin’s poem “Upgrading” reflects this impulse: a catalogue of the elements he seeks not merely to sustain life, but to savour it—without feeling he is missing anything essential. His urge to expand his personal space arises from a sense of emptiness. Though his aspirations may not be realistic, realism becomes irrelevant when the mind possesses the power to transcend the limits constructed by reality around dreamers. Life, in this view, is not a reference point for something else—it is a guidebook for the many lives we live, quietly, and without harm.

And how about a mountain or two in the living room, each topped with ancient pines like overgrown bonsai. My own moon, that I can switch on or off with a flick of the wrist. A sun with a built-in dimmer. Stars to deck my Christmas with.

Rooms the size of night. Perfect quiet. Space at last to dream of islands without end.

Human beings encounter and absorb the external world through the five senses. Among them, taste is perhaps the one that most readily establishes itself through surrender. It becomes erotic—even when what is being offered borders on disgust. In the poem “The Memory of Your Taste”, the poet recalls a profound past experience, tracing it through the sensory and biological pathways of memory.

What do we do when tasting a meal—or a human being? We measure. We make the sensation comprehensible through touch. We heighten the erotic charge by discovering the right pathways. The poet sustains this lyricism with precision, each image striking a resonant note. The nature of the taste itself is secondary; what truly matters is the intensity with which we inhabit this most intimate of senses.

…delectable sheet scribbles every wet lick

on nosetip and earlobe the hollow of your

collarbone, sloped syntax of peak and peak, how

the slick shimmies through plain towards forest

of fingers at air and hair there, there…

Walt Whitman writes: That you are here—that life exists, and identity; that the powerful play goes on, and you may contribute a verse. It is, indeed, revolutionary to have something of ourselves inscribed—on a page, on a wall beside a rubbish bin, or upon a lover’s body. That verse affirms and solidifies our identity. In the prose poem Song, the poet acknowledges both the vulnerabilities and the strengths inherent in being human. He urges us to pursue our purpose and not to relinquish our faith in passion and in art.

Pang’s belief lies not in mere endurance, but in the acceptance of pain—as it is through pain that we may find voice. He calls on us to turn inward, to ask who we truly are. Whether or not that question yields an answer is, ultimately, beside the point. The experience itself must not be dismissed. For many of us, it is precisely such moments that expand the lungs, allowing us to breathe more fully—and, perhaps, to die laughing.

the perch is equal to the burden of water, so is the trout. lovers who drown in two skies are reborn as finches, fog is lifting from the crimson plains.

we are furrow. we are the worn path. so unmoor your throat, swan-eagle, take in the shaft of light, become a field where frequencies nest.

In the realm of poetry, there are few collections quite like All That is Left of the Sea. It is a work capable of inviting us to dream—and then to manifest that dream until it becomes our own reality. So few contemporary poets manage to be as sensitive, as tender, and yet as unflinchingly honest as Alvin Pang. This collection serves as a masterclass in modern poetry, attuned to the complexities of the present world.

Pang’s voice will echo around us—and those who truly hear it may find themselves transformed into amalgams of buds and bullets. If we choose to become buds, we will bloom. If we take on the identity of bullets, we make space—for other buds, their fragrance, and their enduring, prolific presence.

How to cite: Deb, Kabir. “A Bubble of the Sea Holds the Cosmos and Its Caricature: Alvin Pang’s All That is Left of the Sea.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 5 Aug. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/08/05/of-the-sea.

Kabir Deb is a writer based in Karimganj, Assam. He is the recipient of the Social Journalism Award (2017); the Reuel International Award for Best Upcoming Poet (2019); and the Nissim International Award (2021) for Excellence in Literature for his book Irrfan: His Life, Philosophy and Shades. He reviews books—many of which have been published in national and international magazines. His most recent work, The Biography of the Bloodless Battles, has been shortlisted for the Sahitya Akademi Yuva Puraskar (2025) and the Muse India Young Writer’s Award (2024). He currently serves as the Interview Editor for the Usawa Literary Review. Instagram: @the_bare_buddha [All contributions by Kabir Deb.]