📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

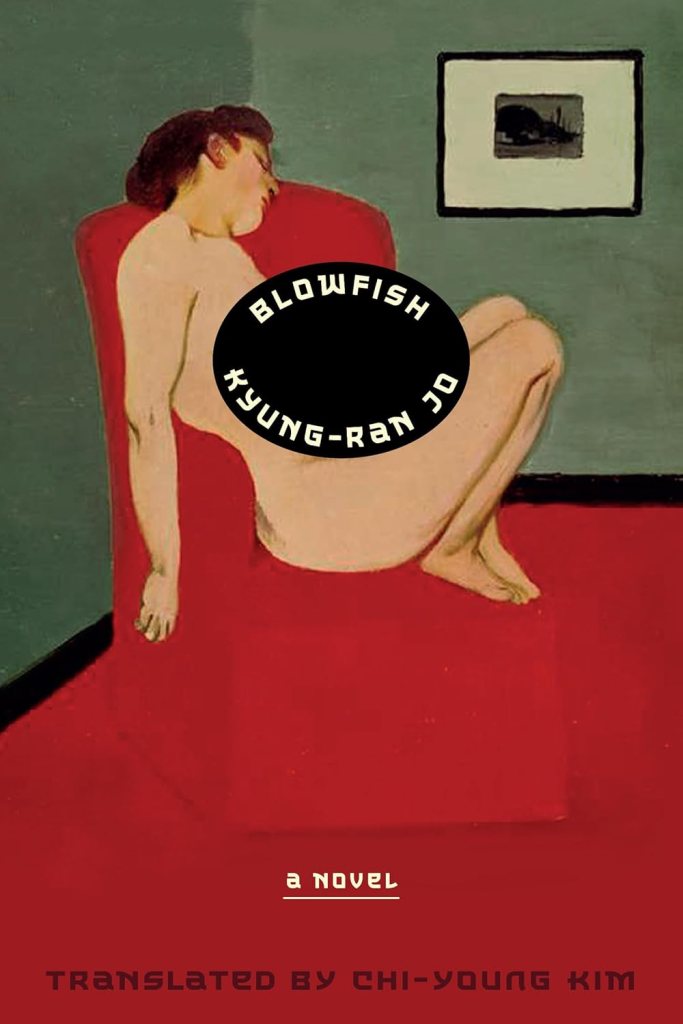

Kyung-Ran Jo (author), Chi-Young Kim (translator), Blowfish, Astra House, 2025. 304 pgs.

Blowfish is a taut, deceptively quiet novel, structured as a contrapuntal meditation on grief, disconnection, and stillness. The stillness seethes beneath the surface—like the lethal calm of the fish, a creature whose presence in the novel is metaphorical. The narrative unfolds through alternating perspectives: two unnamed narrators whose interior worlds spiral inward while the world around them remains largely indifferent.

The first is a sculptor, successful by “external” standards, whose work is exhibited across Korea and Japan. Yet behind this public façade lies a woman quietly unravelling, her grief and loneliness calcifying into a plan for suicide. Her chosen method—death by blowfish—carries familial echoes: it is how her grandmother died. Her grandmother once prepared a bowl of blowfish soup and drank it. Her father, broken by that memory, stumbled through life. And the sculptor knows that grief can be inherited. The fish is her medium now.

The architect who narrates the alternating chapters is a man similarly haunted. His brother’s suicide fractures his sense of moral and narrative order. Unlike the sculptor, whose suicidal ideation is internal, almost methodical, the architect is forced to confront death as something abrupt and grotesquely visible. He arrives home to find a body shattered on the asphalt—a body he realises is his brother’s. His reaction, disturbingly glib on the surface (“Why the fifth floor? Couldn’t you have jumped from a smaller one?”), reflects the human tendency to mask devastation in rationality, cruelty, or absurdity.

What forms the narrative is not merely what happens, but how little of it occurs in a conventional sense. Even the characters’ names are withheld until they meet. This meeting does not serve as a neat narrative resolution but rather as a further complication. Jo’s prose is measured, almost meditative, with sparse descriptions that carry disproportionate weight. But like the finest architecture, its beauty lies in its spaces—the silences, the ellipses, the parts we cannot see or fully grasp.

But just as she moves inward—towards silence and retreat—the architect moves outward, towards confrontation. He has seen death fall from the sky. When he sees the sculptor again, on the roof of a skyscraper in Tokyo, he recognises the look in her eyes. It is the same look his brother wore, moments before disappearing. The same stillness before collapse. It opens a fissure in him. He does not know what he wants from her—only that he wants to stay. To see. To not flee this time. Two people touched by death find each other.

But Blowfish is far more entangled than that. The sculptor approaches her pain in the only way she knows how. The planning of her death mirrors the construction of a work of art. She prepares meticulously, as artists do—studying textures, rituals, shapes. She even carries a folding chair to Ueno Park. The grandmother speaks to her, or appears to, and though their encounter is neither sentimental nor overtly redemptive, it unsettles the artist’s resolve. She walks away from the park alive, but not because she has chosen to live. Rather, the method must change. She fixates now on the same method her grandmother used: the blowfish, beautiful and deadly. She purchases a book titled Understanding Blowfish.

Eventually, she meets Abe-san, the gruff master of the last stall that still sells blowfish. Their relationship is brusque, respectful, and eventually intimate—not in any romantic sense.The chapters alternate between the sculptor and a young architect who carries his own weight of grief, having lost his brother to suicide not long ago. He remembers vividly the day he arrived home to find his brother’s body splayed on the road. His father now deteriorates under the slow erosion of depression, and his mother bears the burden in a silence he cannot yet understand.

When the architect sees the sculptor again, on the top floor of a Tokyo skyscraper, he recognises the look in her eyes. It is the same look his brother wore—an expression emptied of hope, but not of meaning. He does not know what she intends—only that he cannot look away. The sculptor has no interest in being saved; the architect has no vocabulary for offering solitude.

Blowfish is full of restless currents, both between chapters and within them. The characters are always moving inward and outward, retreating and reaching. For all her focus on dying, the sculptor remains curiously engaged with the world—she watches subways, she draws, she tastes. The architect, too, is caught between action and paralysis, wanting to build, to love, to understand, but unsure how. The novel is heavy, but not in a self-indulgent way. Rather, it is weighty in the way that real grief is. The prose is spare, but not flat.

And yet, while the structure and themes coalesce into a powerful literary object, the English translation feels, at times, like a pane of fogged glass. One senses something intricate and moving just behind the words, but the surface occasionally fails to transmit the emotional heat. Jo’s style depends on tonal calibration—on emotional precision. In translation, some of these modulations are dulled; certain passages feel rushed, clipped, or syntactically awkward.

How to cite: Singh, Ananya. “To Stay, To See, To Not Flee: Kyung-Ran Jo’s Blowfish.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 5 Aug. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/08/05/blowfish.

Ananya Singh is a writer. Her work has been published in FirstPost, Deccan Herald, Madras Courier, and elsewhere. She can be contacted via ananyadhiraj7@gmail.com and @anannnya_s on Instagram and X. [Read all contributions by Ananya Singh.]