Editor’s note: Lydia Wong’s evocative essay explores salt as both a material and metaphorical force in Hong Kong’s cultural, political, and sensual identity. From ancient salt fields to contemporary political repression, she traces how salt symbolises preservation, resistance, and longing. Blending personal memory, linguistic insight, and historical reflection, Wong links salt’s transformative nature to the city’s fading freedoms and irreverent spirit. In a Hong Kong where the kinky, chaotic vitality once flourished, she asks—how do you preserve what is already made to preserve?

Salt’s preservative properties are well known.

Favourite dishes in Hong Kong often feature salt-cured produce—salted fish and lap cheong, a richly seasoned sausage saturated with salt. Salt draws moisture from the flesh, inhibiting the microorganisms that would otherwise cause it to spoil. The fibres are materially altered in the process; in return, they are granted longevity. Salt gives by transformation.

Salt also breathed industrial life into Hong Kong. I discovered this only recently, in Louisa Lim’s Indelible City (2022)—a book that traces Hong Kong’s cultural and historical foundations. As early as 222 CE, salt had become the region’s earliest industry, with over one hundred kilns operating across the expansive Guanfu Salt Fields.

This history of salt also bears the imprint of rebellion. In response to the imperial Chinese government’s monopoly on salt production, local producers staged numerous uprisings. These stories were never part of our school curricula. Instead, we absorbed the British colonial narrative: that Hong Kong was a dormant fishing village, awakened only by colonial rule. The present-day Chinese state, allergic to dissent of any kind, likewise refuses to acknowledge this legacy of resistance.

Salt bears a profound historical weight—it signifies a concealed, often erased chapter of Hong Kong’s past. It was a site of labour and defiance, a legacy that echoes in our recent struggles for local autonomy. Salt tells us how Hong Kong began, and it remains encoded in the core of who we are.

My desire for preservation was ignited by the profound political shift of 2020—the year Hong Kong’s civil liberties suffered a grievous blow in response to waves of pro-democracy protests over the preceding decade. The curtailment of freedom of speech was particularly painful; I never imagined Hong Kong would become a place where uttering a slogan could lead to imprisonment. Watching political activists jailed or forced into exile was heartbreaking—this was the kind of thing that happened in other countries… until it didn’t.

It brought with it a deep and disorienting grief. Though geographically unchanged, it felt as though something vital had been lost. I find myself looking back to the ’80s, ’90s and 2000s—decades for which many Hong Kongers feel immense nostalgia. A time when Hong Kong was allowed to flourish, confident in who she was—an identity that now seems to be slipping away.

The most remarkable thing about Hong Kong in that era was that she was the perfect amount of salty, and the right degree of wet.

Salty wet (鹹濕), pronounced ham sup, is the colloquial Cantonese term for perversion. Some unsavoury uncles were rightly dubbed ham sup lo (perverted man), yet anyone with an explicit interest in sex might also be labelled ham sup by more prudish members of society.

This distinction matters—for while ham sup can imply a judgement of impropriety, it can equally describe those who express desire consensually and openly, with exuberance rather than harm. Ham sup can speak to craving—to those who boldly colour outside the lines without descending into immorality. In this way, Hong Kong has always been a little salty wet.

I felt this viscerally as I wandered the city in the ’90s and 2000s. By day, the air was thick with humidity and laced with pollution; your skin would immediately grow slick with salt, everything impossible to keep dry or pristine. By night, the electrolytes lingering on your skin cooled to a tingling charge. That electricity was uniquely Hong Kong—its own particular kink that made us feel inexplicably alive, and deeply proud to belong to this city. Not perverse, nor shameful—just hungry in our own way.

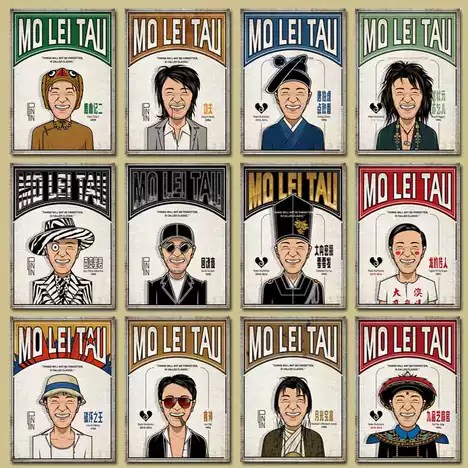

The idea that Hong Kong was kinky first emerged on a beer-soaked evening in the mid-’00s, when I was out drinking on the streets of Tsim Sha Tsui—well past curfew. A friend mused on a saying commonly attributed to Martin Lee, our local father of democracy: Hong Kong didn’t have true democracy, but we felt truly free. There was no universal suffrage, yet we had a trusted rule of law that afforded us freedom of speech, separation of powers, and crucial civil liberties. This gave us the space to indulge—with equal abandon—in casual political engagement, the absurd slapstick humour of Mo Lei Tau (無厘頭—literally “without sense”), and Hong Kong’s fetish for capitalism.

At this juncture, a quiet anxiety about the city’s future began to brew, as we lived under the framework of “One Country, Two Systems”: Hong Kong was part of China, yet retained its own rule of law. For the most part, we believed the framework was being honoured, even though the foundations underpinning it remained uncertain.

A small group of vocal democracy advocates and politicians remained visible—their presence reassuring us that politics was not, as yet, an existential threat. Most people tuned in to the highly influential radio programme Storm in a Tea Cup (風波裡的茶杯), known for its fiery and open political discourse. The show’s title perhaps captured our naivety and optimism—as though our gravest concerns could be contained within something as slight as a teacup. We were acutely aware of the privileges we enjoyed compared to our mainland compatriots, and even took pride in our relative freedoms, but most of us slid into complacency. We felt secure enough in our civil liberties to treat politics lightly.

Originally a genre of Hong Kong cinema, Mo Lei Tau became a unifying cultural kink. Via.

That sense of safety allowed us to indulge in Mo Lei Tau and other hedonistic, capitalist pursuits. Originally a genre of Hong Kong cinema, Mo Lei Tau became a unifying cultural kink—about being seriously silly, and celebrating nonsense. It was a cultural mood, a way of enjoying freedom through messy humour and cheerful absurdity. Such everyday creativity is only possible when one feels secure in their autonomy—and our almost-democracy offered just that. Alongside a shameless appetite for capitalism and a considerable measure of political liberty, Hong Kong—so we all drunkenly agreed—thrived in her own brand of kink and chaos.

Fast forward to today: after a decade of protests and the subsequent imposition of draconian legislation, we have become State law and State order. Our beloved kink has dimmed to a dull hum. You can still hear her, if you listen very closely—or seek her out underground. It is clear this salty, wet spirit must be preserved. But how does one preserve salt itself?

Last November, I visited Yim Tin Tsai (鹽田仔—literally “Little Salt Pan”), Hong Kong’s last remaining operational salt production site, situated on a tiny outlying island. The site was originally established by a Hakka clan who arrived in Hong Kong from southern China in 1670, and is now cared for by the Salt and Light Preservation Centre—a conservation project founded by the clan’s descendants.

Salt pans are flat, shallow basins where salt is harvested from the South China Sea. Sun and wind evaporate seawater collected in these pans, leaving behind a concentrated brine. This brine is transferred through a series of pans, each with increasing salinity, until salt crystals begin to form—at which point they are raked and gathered.

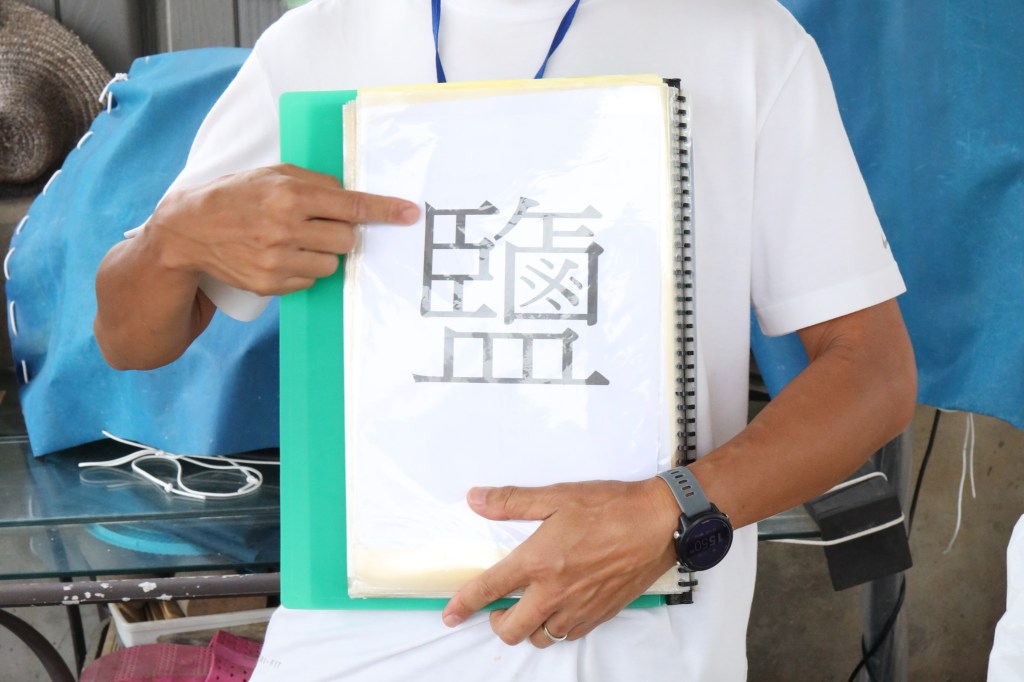

Our guide shared the etymology of the Chinese character for salt. Embedded in the top left is the character for governance—salt was a precious mineral that demanded state control. At the top right, symbols for labour and seawater—salt production requires concerted effort from both humans and nature. At the base, grids resembling salt pans—containers, not unlike human vessels, catching all that salty wetness trickling down.

This character encapsulates both the material and cultural significance of salt to Hong Kong. There is another colloquial term for kinkiness: heavy mouth taste (重口味). Salty dishes are aptly described as savoury because of salt’s power to intensify flavour. Salt preserves more than just food—it holds memory, and it captures the spirit of our city. We owe so much of what we savour to salt, and to the wetness that carries it to us.

The harsh sun and strong winds force salt to crystallise from water. Yet through the living ecology of the world, salt always finds its way back. Salty is never far from wet.

A guide explaining the etymology of the Chinese character for “Salt” 鹽 at Yim Tin Tsai

Pans and tubs at Yim Tin Tsai

Playing with salt at Yim Tin Tsai

Header image: “Salted Fish, Peng Chau”, December 2019 © Oliver Farry.

How to cite: Wong, Lydia. “SALTY WET 鹹濕.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 22 Jul. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/07/22/SALTY.

Lydia Wong is a Hong Kong–born artist based in London. Through sculpture, video, installation, and performance, she explores how identities and a sense of place are shaped and sustained—particularly in the face of political erasure. Drawing on Taoist geomancy and Feng Shui, she recently flew crab-shaped kites on drones—embodied archives dispatched to the other world. She also set alight a paper effigy of a giant blue flower crab—a fiery offering of memory to the afterlife. These acts of resistance and transformation are documented at www.lydiawong.co.uk.