📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

Click HERE to read all entries in Cha on A Woman Burnt.

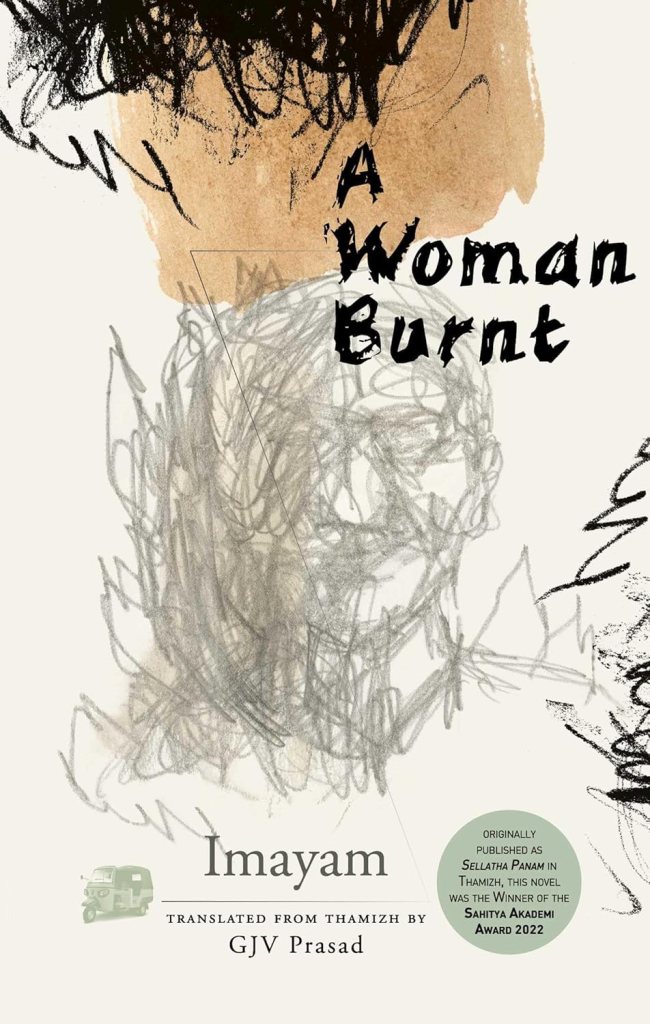

Imayam (author), GJV Prasad (translator), A Woman Burnt, Simon and Schuster India, 2023. 336 pgs.

“Every woman adores a Fascist, / The boot in the face, the brute / Brute heart of a brute like you,” writes Sylvia Plath in her poem “Daddy”, invoking a disturbing metaphor of women internalising abusive power structures. This internalisation of oppression has long been depicted as “normal” across cultures and societies, with women accepting subordination as their natural condition. Literature and other cultural expressions have played a pivotal role in reinforcing this discourse as part of the natural order.

Yet it is through literature itself that writers have sought to interrogate and subvert this order. In the Indian context, a new wave of writing has begun to challenge these entrenched patterns of female subjugation. Among such voices, Imayam—a Tamil writer active since the 1990s—has emerged as a singular chronicler of women’s experiences. Nearly all his major works—from Koveru Kazhudaigal (Beasts of Burden, 1994) to Sedal (2004), to Selladha Panam (A Woman Burnt, 2018)—centre on women protagonists who are victims of a patriarchal society, holding up a mirror to contemporary Tamil social realities. But what makes Imayam’s works so compelling is that he does not merely portray women as helpless victims. Rather, he arms them with an axe—through silent dissent, incisive dialogue, or bold articulations, his female characters crack open the edifice of patriarchy. A Woman Burnt, originally written in Tamil as Selladha Panam, is one such axe: it exposes patriarchal structures and women’s subordination while confronting, head-on, the enduring ‘woman question’.

The narrative revolves around Revathi, an engineer who marries outside her caste against her parents’ wishes and ultimately meets a tragic end—burnt alive. Readers, alongside the characters, are led to suspect her abusive husband, Ravi, as the likely perpetrator. But the novel’s true power lies in its ability to redirect the reader’s gaze—from the sensationalist question of who burnt Revathi to the far more unsettling and systemic question of why she was condemned to burn in the first place. India continues to witness countless women who self-immolate in desperate attempts to escape abusive marriages and oppressive families. It is this brutal, everyday reality that the novel captures—the psyche of such women, and the myriad catalysts that render them victims of a deeply gendered social structure.

Put simply, it is the story of a woman caught in the crushing nexus of caste, class, culture, and marriage—left suspended between life and death, a living metaphor for countless Indian women. The novel’s strength lies in its refusal to succumb to reductive binaries. Instead, it reveals characters acting in accordance with their social conditioning rather than abstract notions of morality. It looks beyond political correctness to reveal how complicity is embedded across all levels—using a polyphonic narrative to expose the latent cruelty within individuals and institutions alike. At a pivotal moment, Ravi, the husband, declares: “I didn’t burn Revathi—you burnt her” (p. 238), directing his rage at the parents who severed all ties with her for transgressing caste and class boundaries in her marriage.

Throughout the novel, a persistent feminine consciousness captures not only the desperate struggle to break free from patriarchal oppression but also the ways in which women themselves become complicit in upholding these structures—clinging to the image of the “ideal woman” in order to survive. The novel’s power is crystallised in its title, which becomes a haunting metaphor for the entire narrative. The unresolved mystery of how Revathi was burned mirrors the unresolved question of women’s subordinate status in society.

Imayam has written a novel that does not merely tell a story—it wields that essential axe to crack open uncomfortable truths about gender relations in contemporary India. Though he breaks the mirror that reflects society’s treatment of women, his female characters are still struggling to step beyond its fractured surface.

How to cite: Rath, Swgatika. “Portrait of a Burning Woman: Imayam’s A Woman Burnt.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 14 Jul. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/07/14/burnt.

Swagatika Rath is a postgraduate student in the Department of English at Pondicherry University. Her academic interests encompass translation, creative writing, and content writing. She has participated in various literary conferences and has published research papers and book reviews in esteemed journals and publications.