📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

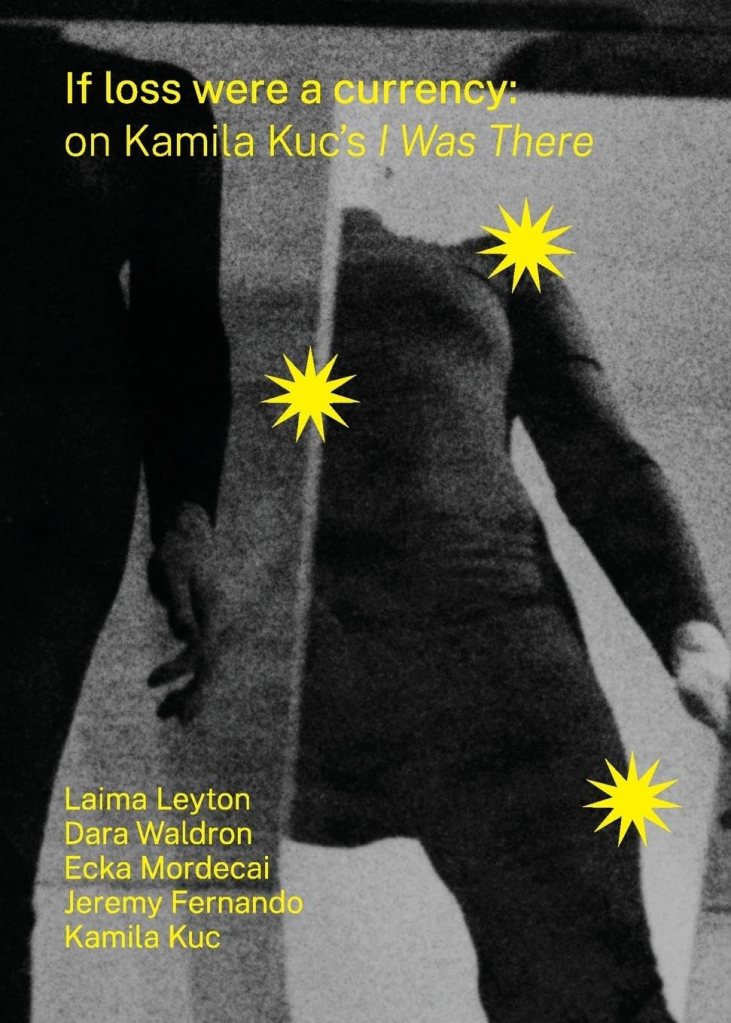

Kamila Kuc, Laima Leyton, Dara Waldron, Ecka Mordecai, and Jeremy Fernando (contributors), If loss were a currency: on Kamila Kuc´s I Was There. Delere Press, 2025. 114 pgs.

According to psychoanalysis, trauma is the experience of something that no speaking, no writing can ever fully represent. In trauma, we are violently and helplessly subjected to the outside of words and sentences—to a realm beyond meaning, beyond the normal and effortless identification of things and events. Words must fail, for no word seems adequate; images must fail, for no image can capture unimaginable horror or convey indescribable loss. What trauma leaves us with is, therefore, only silence or stammer: the silence of voices that wish to speak but cannot—or the stammer of voices that do speak, in spite of everything, but uncertainly, gropingly, nonsensically, in search of a sense that continuously eludes them. If language, as Martin Heidegger famously declared, is the house of being, then the traumatised individual is a stranger in this house—no longer at home among words and meanings.

If loss were a currency: on Kamila Kuc’s I Was There (Delere Press, 2025) is a collection of essays and poems that all engage with questions of loss and trauma, viewed through the temperaments and sensibilities of five authors and artists: Laima Leyton, Dara Waldron, Ecka Mordecai, Jeremy Fernando, and Kamila Kuc. The collection revolves around filmmaker Kamila Kuc’s personal experiences of loss—the loss of her Polish grandmother, Helena—and Kuc’s attempt to address this loss, to depict this wound in the film I Was There. Trauma builds upon trauma in the film as well as in the book: in addition to the trauma of the loss itself, there is also, as we learn, the trauma Helena carried with her for most of her life, having lived through the horrors of the Second World War and been exposed to the unfathomable brutality of the Nazis. The death of Helena, the emptiness she leaves behind, is thus coupled with experiences of war and cruelty that were never truly left behind, never laid to rest, but remained always far too present—present in the absence of words, present in a past that cannot be passed.

“I search for words but my best version of Polish is silence,” says Kuc in the film. Thus, to be fluent in silence—to have silence as one’s mother tongue, to be born to excel in silence: nothing could be easier, and yet nothing could be harder. Silence is hard because experiences that are never verbalised, never expressed, are, in fact, not experiences at all—not sufficiently externalised to become something graspable, something manageable, and thus something passable. Where the “ex” of ex-perience is lacking, we are left with nothing but the periri—that is, with nothing but endless tests and trials. These are the solitary trials that haunt every silence and that, indeed, make a Polish silence different and distinct from any other silence—make my silence different from yours. Because our silences will always be haunted by different ghosts, what is unsaid is never exactly the same. Each silence is charged and burdened in its own way—each silence indefatigably “speaks” its own unique and inimitable silence. As Jeremy Fernando writes:

One sometimes wonders if silence speaks loudest not only because it signals to an absence, or an inability to articulate despite wanting to, but that it reminds us that even in whatever is said, uttered, yelled, there is always also a silence accompanying it, walking beside it, within it. And it be tales which hold on to these silences who speak loudest to us.

If loss were a currency is, in many ways, a haunted book—a book of spectres appearing on the very thresholds of language and meaning, allowing no word to pass surely or swiftly before our eyes. It is as if the authors present us—as Maurice Merleau-Ponty once said of Cézanne’s and Picasso’s paintings—with things, places, and events that stand “bleeding” before us, still surprised by their own birth on the page. If chatter expresses a language all too certain of its meaning—and in its very certainty soon empties and loses itself—then here we are confronted with the hesitant birth of meaning, the very first encounters with a significance that is still unsettled and thus remains always yet to come. If loss were a currency thus situates us on the side of creation rather than finality, on the side of experimentation rather than stabilised truths. Its stammer, if we may call it thus, is the stammer of poetry and of art entering unknown land. And we, as readers, are invited into this opening—into this clearing that is also a wound—to reflect on our own losses, to confront our own silences, to contemplate our own wounds—wounds that are as impossible to share as they are impossible not to speak of.

How to cite: Kølle, Anders. “Whereof One Cannot Speak, Thereof One Cannot Stay Silent—On If loss were a currency: on Kamila Kuc´s I Was There.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 13 Jul. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/07/13/loss-currency.

Anders Kølle is lecturer of Communication Arts at Khon Kaen University, Thailand. Holding a PhD in Media and Communications from The European Graduate School, he has taught art and philosophy at several universities, including the University of Copenhagen and Assumption University, Bangkok. His work focuses on contemporary encounters between philosophy and art, and on art’s potential to produce new modes of thinking and create new forms of critique. His publications include On Being Ridiculous (Delere Press, 2024), The Technological Sublime (Delere Press, 2018), and Beyond Reflection (Atropos Press, 2013). [All contributions by Anders Kølle.]