📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

Ryan Dunch and Ashley Esarey (editors), Taiwan in Dynamic Transition: Nation Building and Democratization, University of Washington Press, 2020. 256 pgs.

Taiwan has long been a focal point in the study of Pacific geopolitics since the main phase of the Chinese Civil War ended in 1949. Yet, as Thomas Gold observes, Taiwan was largely overlooked as a subject of inquiry in other subfields of (Western) political science, dismissed as an “ossified… Cold War relic” and “downright boring.”1 This oversight seems particularly odd: the Taiwanese people’s struggle against authoritarian, single-party rule and their search for national identity constitute a nuanced and complex historical trajectory—one well worth examining in its own right, as the anthology Taiwan in Dynamic Transition: Nation Building and Democratization (edited by Ryan Dunch and Ashley Esarey) and earlier scholarship aptly demonstrate. That Western political science literature on authoritarianism and democratisation largely neglected Taiwan’s political development is especially conspicuous when set against the vast corpus devoted to analysing the persistence of Chinese authoritarianism and forecasting its potential collapse.2 This may point to a broader pattern in which American political analysts have tended to focus on the presence or absence of democracy solely in Communist-led regimes—suggesting that the erstwhile indifference to Taiwanese politics may itself be a Cold War relic.

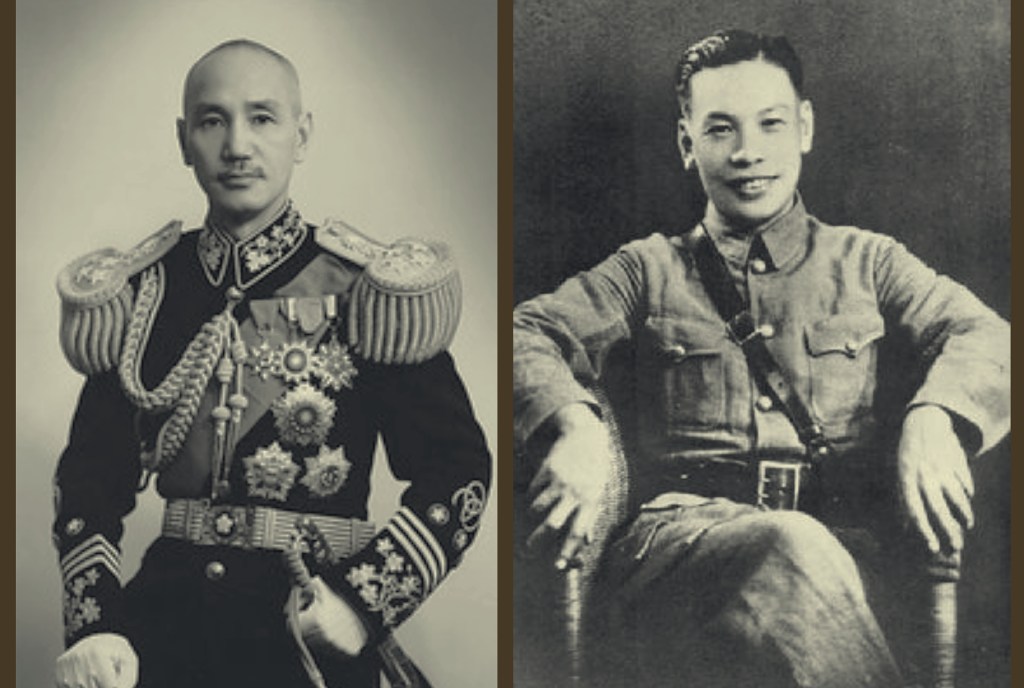

Editor Ryan Dunch articulates the anthology’s central thesis clearly in the introduction: that Taiwan merits analysis “on its own terms”, and that such analysis can meaningfully inform broader scholarly debates on national identity formation and democratisation movements. Ashley Esarey’s historical overview of Taiwan’s democratisation then offers a compelling case that the island’s political evolution during the martial law period was far from inert. While the Kuomintang (KMT), under Chiang Kai-shek and his son Chiang Ching-kuo, was undeniably repressive and sought to penetrate Taiwanese society in what Cheng Tun-jen (1989) characterises as a “quasi-Leninist” fashion, the regime’s grip on power was far from absolute. It made calculated concessions towards democratisation in an effort to forestall questions of legitimacy, even as it continued to suppress political dissent.

Chiang Kai-shek and Chiang Ching-kuo. Via.

The prevailing narrative, perhaps, holds that the Republic of China’s declining international stature rendered these democratic concessions inevitable (see, for instance, Thompson 2019). Yet a closer examination reveals that Taiwan’s democracy movement has deep roots in earlier campaigns for self-rule under Japanese imperial rule—and arguably further back still, in Aboriginal Taiwanese resistance to colonial domination. The Taiwanese identity itself, it is argued, is similarly longstanding and deeply embedded.

The volume’s first two chapters elaborate on Taiwan’s history as a nation-building project. In “Nation-State Formation at the Interface”, Rwei-Ren Wu traces Taiwan’s long and layered experience of colonial rule as an “interface between powerful states”, arguing that the policies of the Qing dynasty, Imperial Japan, and the early Republic of China inadvertently laid the groundwork for the Taiwanese sovereignty movement. These regimes, through their exploitative and assimilationist policies, provoked political resistance that would ultimately crystallise into demands for self-rule. Wu’s approach bears resemblance to that of Chu and Lin (2001), who analyse Taiwan’s political development under both Japanese and authoritarian KMT regimes. However, whereas Chu and Lin contend that there was “no tangible support” for a national sovereignty movement by the time the Japanese empire effectively ceded Taiwan to the Republic of China in 1945, Wu identifies a continuous thread linking the self-rule movement under Japanese colonial rule to the democracy movement under the KMT—even if the composition of pro-sovereignty coalitions evolved in response to the KMT’s introduction of new social divisions. (Esarey’s historical overview posits yet another continuity, noting that early opposition to KMT authoritarianism mirrored earlier resistance under Japanese rule, employing similar strategies of organisation, such as the use of printed periodicals to disseminate political critique.)

Wu’s contribution also enriches the literature on the formation of Taiwanese national identity by demonstrating how a consolidated sense of Taiwanese-ness emerged from the marginalisation of the island’s diverse inhabitants—particularly under Japanese imperial rule. His view resonates, to some extent, with that of Ming-sho Ho (2022), who argues that Taiwanese resistance to Japanese authority was shaped by the Wilsonian principle of national self-determination, as disseminated through American influence. Wu’s account challenges earlier claims that Taiwanese identity only emerged in the 1990s (see, for instance, Brown 2004), pushing the timeline of identity formation further back into the colonial period.

Whereas the first chapter offers a detailed assessment of the origins of the Taiwanese national movement, “Taiwan’s Constitution: Incremental Reform and Prospects for Future Revisions” by Jiunn-Rong Yeh bookends the volume’s treatment of the subject by surveying the country’s constitutional reforms from 1991 to 2005. These reforms largely entailed shedding the final vestiges of the Republic of China’s rule over Taiwan as a province and transferring political power directly to the Taiwanese people—most notably through the dissolution of outdated political institutions such as the National Assembly and the lifelong legislative appointments of representatives from mainland Chinese provinces.

Yeh focuses in particular on the 2005 reforms, which marked a turning point in Taiwan’s electoral politics. These changes included not only a significant restructuring of the Legislative Yuan but also the introduction of stringent requirements for any future constitutional referenda. (As of 2005, a constitutional referendum must first secure a three-fourths majority in Taiwan’s polarised legislature, followed by a public vote requiring six months’ notice and the participation of at least half the electorate.)

Revisions to the ROC constitution are arguably central to Taiwan’s modern state-building project, given that the island inherited a constitutional framework designed for—and oriented toward—the governance of China. Yet the 2005 reforms, while encouraging legislative candidates to build broad-based coalitions, may have set the bar for further constitutional change so high as to entrench the existing system.

Even prior to 2005, referenda were difficult to pass. Yeh cites the example of the 2004 referendum on cross-Strait relations, in which both measures received the support of over 90 per cent of voters—but, partly due to KMT-led boycotts, failed to meet the required quorum because overall voter turnout fell just short of the 50 per cent threshold.3

Although Yeh attempts to identify the conditions under which future constitutional referenda might succeed—arguing, for instance, that synchronising a referendum with a major election could be key to meeting turnout requirements—the combination of high electoral thresholds and entrenched rivalry between the KMT and DPP raises the question of whether constitutional reform in Taiwan has already reached its limits.

The remaining chapters of this volume offer a multifaceted perspective on the state of Taiwanese democracy, generally commending the breadth of civic participation while also drawing attention to underlying causes of political dysfunction and division. Chapters Three and Four present two complementary perspectives on the robustness of democratic engagement and participation in Taiwan.

In “Neighborhood Politics in Taipei: Democracy at the Most Local Level”, Benjamin L. Read—who published a 2012 monograph on neighbourhood organisation and social networks in Beijing and Taipei—examines the local elections for Taipei’s neighbourhood wardens. These elections are strikingly democratic, marked by extensive face-to-face community engagement and more institutional formalisation than is found in many liberal democracies. They also exemplify Taiwan’s increasing political pluralisation since the end of martial law: whereas wardens were once largely hand-picked by the KMT, they are now more often political independents, particularly outside Taipei.

TVBS news still of Pang Weiliang 龐維良, candidate for reelection as neighbourhood warden of Longquan Village 龍泉里 in Taipei, 2014.

From another angle, Kelly W. Chen portrays the Sunflower Movement as a vivid manifestation of Taiwanese youth political engagement and the effective coordination of civil society groups, in the chapter “Island Sunrise: The Sunflower Movement and Taiwan’s Democracy in Transition”. Chen’s reading of the movement’s legacy is relatively sanguine;4 yet its successful mobilisation of NGOs and other civil society actors is significant, and her assertion that the movement reflects a consolidated Taiwanese identity—especially among the youth—is substantiated by recent survey data.5

Democracy in Taiwan, however, is not without its challenges, as illustrated in Chapter Five, “Taiwan’s Death Penalty: The Local–Global Dynamic” by Chia-Wen Lee. Lee notes that, despite considerable political momentum to abolish capital punishment—both as a moral distinction between the DPP-led “new government” and its KMT predecessors, and in keeping with Taiwan’s human rights commitments—policy decisions in this area have remained largely driven by electoral calculations and, at times, diplomatic considerations.

The final two chapters underscore how democratic engagement extends into public attitudes towards Taiwan’s military and defence sector, particularly regarding the mistrust generated by past scandals. In “Scandal and Reform: Democracy and Taiwan’s Defense Sector”, Eric Setzekorn discusses how arms procurement controversies in the 1990s and 2000s, along with the death of Corporal Hung Chung-chiu in a 2013 abuse-of-power case, spurred reforms that increased civilian oversight and transitioned the military from conscription to a volunteer-based system. Yet Setzekorn observes that these scandals carried a “spillover cost” to the military’s public image, with public distrust limiting support for increased defence spending—an issue further explored in Ja Ian Chong’s chapter, “A Matter of Trust: Understanding Limited Public Support for Taiwan’s Defense Reform”.

A broader concern emerging in the final chapters—particularly in the contributions by Lee and Chong—is the question of whether Taiwan’s democratic politics can be considered fully sovereign. China’s growing assertiveness appears to constrain the Overton window of domestic political discourse; the United States’ protective umbrella is accompanied by pressure to conform to a US-led trade agenda; and Taiwan’s diminished international status encourages policymakers to prioritise the views of foreign democracies, sometimes at the expense of the preferences of the Taiwanese public themselves.

The contributors to Taiwan in Dynamic Transition offer valuable portrayals of Taiwan’s wide-ranging successes in its calculated assertion of sovereignty and its gradual shedding of its authoritarian past—albeit not without the challenges inherent in pluralistic politics. The detailed case studies and comparative analyses presented in this volume constitute meaningful progress towards the editors’ stated aim of analysing Taiwan on its own terms. Yet this aim is somewhat compromised by the recurrent appearance of China as a political factor in every chapter except Read’s assessment of local politics.

The spectre of China’s declared intention to compel—or force—unification with Taiwan looms over efforts to build a Taiwanese nation and practise full democracy; public polling on the meaning of independence, referenda concerning foreign relations, and the unresolved question of whether to change the Republic of China’s official name all bear witness to this persistent pressure.

Nonetheless, the contributors to Taiwan in Dynamic Transition make a compelling case that the study of Taiwan’s politics offers insights that extend far beyond the confines of cross-Strait relations. The volume provides distinctive perspectives on the legacies of imperialism and colonialism, the condition and prospects of a relatively young democratic experiment, and the rare opportunity to observe the formation of a national identity in real time.

- “Foreword.” Taiwan in Dynamic Transition: Nation Building and Democratization. ↩︎

- Numerous examples of such political science studies exist. Starting points for exploring this literature include Bruce Gilley’s 2004 book China’s Democratic Future: How It Will Happen and Where It Will Lead and more recent work such as Carl Minzner’s article “China After the Reform Era” in the Journal of Democracy (2015). ↩︎

- One could argue, too, that the two measures proposed in the 2004 referendum were relatively uncontroversial. The first stipulated that, should China refuse to desist from aiming missiles at Taiwan, the Taiwanese government ought to prioritise the expansion of its anti-missile defences; the second called for the government to enter into negotiations with the Chinese Communist Party on a framework for “peace and stability” in cross-Strait relations. ↩︎

- Assessments of the Sunflower Movement’s enduring influence were decidedly mixed—as reflected, for example, in a panel session at the World Conference of Taiwan Studies held in May 2025, which focused on the Sunflower Movement, the Milk Tea Alliance, and transnational social movements in East and Southeast Asia. Likewise, Brian Hioe’s fictionalised account of the demonstrations at the Legislative Yuan, Taipei At Daybreak, alludes to the protestors’ feelings of listlessness and lack of direction at the conclusion of the occupation. ↩︎

- See, for instance, a 2024 survey by the Pew Research Center, which found that two-thirds of respondents—including 83 per cent of those under the age of 35—self-identify primarily as Taiwanese rather than Chinese: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/01/16/most-people-in-taiwan-see-themselves-as-primarily-taiwanese-few-say-theyre-primarily-chinese/. ↩︎

References

▚ Brown, Melissa J. 2004. Is Taiwan Chinese? The Impact of Culture, Power, and Migration on Changing Identities. Berkeley Series in Interdisciplinary Studies of China. Berkeley: University of California Press.

▚ Cheng, Tun-jen. 1989. “Democratizing the Quasi-Leninist Regime in Taiwan.” World Politics 41(4): 471–99. DOI: 10.2307/2010527.

▚ Chu, Yun-han, and Jih-wen Lin. 2001. “Political Development in 20th-Century Taiwan: State-Building, Regime Transformation and the Construction of National Identity.” The China Quarterly 165: 102–29. DOI: 10.1017/S0009443901000067.

▚ Hioe, Brian. 2025. Taipei at Daybreak. Repeater Books.

▚ Ho, Ming-sho. 2022. “Desinicizing Taiwan.” Current History 121(836): 211-217. DOI: 10.1525/curh.2022.121.836.211.

▚ Huang, Christine and Kelsey Jo Starr. 2024. “Most people in Taiwan see themselves as primarily Taiwanese; few say they’re primarily Chinese.” Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/01/16/most-people-in-taiwan-see-themselves-as-primarily-taiwanese-few-say-theyre-primarily-chinese/.

▚ Thompson, Mark R. 2019. Authoritarian Modernism in East Asia. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US.Natsuko Imamura (2020 [2019]). Hoshi no ko. Asahibunko.

How to cite: de Roulet, Eric D. “Taiwan’s Political Evolution and the Study of Comparative Politics as seen in Taiwan in Dynamic Transition.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 29 Jun. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/06/29/taiwan.

Eric D. de Roulet is an interdisciplinary PhD candidate at the University of British Columbia’s Okanagan campus. His research resides at the confluence of Chinese and Taiwanese scholars’ migratory experiences, international higher education, and the evolving dynamics of great power conflicts—both historical and contemporary. He authored an article for Routed Magazine examining the mounting concerns of Chinese students regarding study in the United States during the early stages of the pandemic. He is presently investigating how Taiwanese students navigate intersecting forms of precarity as they chart their academic and professional futures. Website | Bluesky