📁RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

Ming-sho Ho, Be Water: Collective Improvisation in Hong Kong’s Anti-Extradition Protests, Temple University Press, 2025. 258 pgs.

The Hong Kong protests of 2019, which erupted in opposition to the proposed extradition of fugitives to mainland China’s courts, culminated in what has come to be described as the region’s “second” or “real” return to China—an implicit contrast to the compromised handover of 1997. Inspired by martial arts icon Bruce Lee’s dictum to be “formless and shapeless like water,” the movement evolved into the city’s largest and arguably most significant episode of contentious politics. It was distinguished by its decentralised structure, innovative modes of communication among participants, and its fluid, spontaneous protest tactics.

In Be Water, Ming-sho Ho explores the dynamics of this city-wide uprising through the lens of individual and collective agency, proposing the concept of “collective improvisation,” which he defines as “peer-produced strategic responses without prior planning” (a notion elaborated upon later in the work). He investigates how numerous Hongkongers contributed to the movement and how they adapted in response to the government’s countermeasures. Ho both commends and interrogates the durability of the Be Water protest model and the manner in which activists mobilised through interpersonal networks and spontaneous coordination.

This is a meticulously researched and accessible academic study that focuses primarily on the protests themselves, as well as aspects of the subsequent post-crackdown period. It opens with a symbolic moment of “unity and empathy”—the August 2019 event in which diverse groups of Hongkongers held hands across the territory in an action dubbed the “Hong Kong Way,” echoing the “Baltic Way” of Eastern Europe three decades earlier. Ho interprets this gesture as emblematic of the movement’s improvisational character. The book’s introduction provides a concise overview of the “Be Water” movement, tracing its antecedents from the colonial era to its intersection with contemporary global politics, and considering the immediate consequences of the protests. Elsewhere, personal narratives are interwoven at pivotal moments, grounding the analysis in the lived experience of individuals and rendering the work all the more compelling.

Interestingly, Ho does not present his research methods and data at the outset of the book, but relegates them to an appendix. This editorial decision proves effective in capturing the reader’s attention with a narrative first—although, I must admit, I read the appendix before beginning the main text. His four principal data sources are journalistic accounts, in-depth interviews, field observations, and other published materials. He proceeds to define what constitutes a “protest”—a necessary move, given the fluidity of the events in keeping with the “Be Water” ethos of the movement. Protests are understood not merely as singular actions, but as discrete events marked by spatial contiguity (taking place in the same location), temporal continuity (unfolding over an uninterrupted period), and the generation of new initiatives and spin-offs (subsequent actions by different participants), which may be categorised as distinct episodes.

The period of observation begins in February 2019, with the Hong Kong government’s proposal of the extradition bill, and concludes in June 2020, when the National Security Law was enacted. The protests themselves are classified into three categories: peaceful protests, referring to conventional assemblies and demonstrations that do not seek to cause major disruption or harm; disruptive protests, involving actions intended to interrupt normal functioning without the use of force—such as strikes, traffic blockades, or paralysing government agencies with crowds; and violent protests, characterised by the use of physical force resulting in personal injury or property damage. Each event is assessed individually, and if violent actions remain sporadic, isolated, or inconsequential, the protest is still classified as peaceful.

As a firm believer in situating discourse within its immediate and broader socio-cultural context, Ho considers the years preceding 2019—particularly the disillusionment that followed the Umbrella Movement (UM) of 2014—to be essential. This is the subject of Chapter 1, “Evolving Protesters”. The limitations of peaceful civil disobedience became evident during the UM, along with the constraints of its “static” tactics (such as prolonged occupation) and its reliance on a small number of highly visible leaders. In the wake of 2014, new strategies began to emerge—culminating in 2019 with what might be termed the “flowing water” approach, in many ways the antithesis of the earlier movement. Although the UM is often characterised as a “failure,” it nevertheless gave rise to a new generation of political actors—more localist in outlook, and focused on defending Hong Kong’s autonomy rather than effecting reform in mainland China.

Chapter 2, “The Logistics of Networked Militancy”, examines how “collective improvisation” enabled what had been a tradition of peaceful, civilised pro-democracy activism to evolve into a more militant form. This included the construction of barricades and acts of vandalism, all sustained by an “invisible logistic network” grounded in digital communication. The role of online platforms—such as LIHKG, Signal, and Telegram—is explored in detail, as Ho shows how cyberspace became a vital infrastructure for mobilisation and tactical coordination.

The dynamics of protest—particularly the diffusion of protest activity across the region and the innovative tactics employed—form the focus of Chapter 3, “Flowers Blossoming Everywhere”. Site-specific struggles helped to broaden the movement’s appeal; the often-perceived excessive use of police force galvanised local participation. Ho identifies a “weekly rhythm of participation” as central to the protest dynamics. I recall how timetables and schedules for forthcoming protest actions circulated widely on social media, alongside recurring calls for participation in acts such as “shouting at the window at 10 p.m.”. Lennon Walls—both stationary and mobile—emerged as communal noticeboards, sources of information, and focal points for gathering.

Ho astutely observes that the diffusion of protest locations reinforced the sense that the “lack of democracy” was “a local problem”—an insight that underlines how neighbourhood-level mobilisation translated into broader collective action.

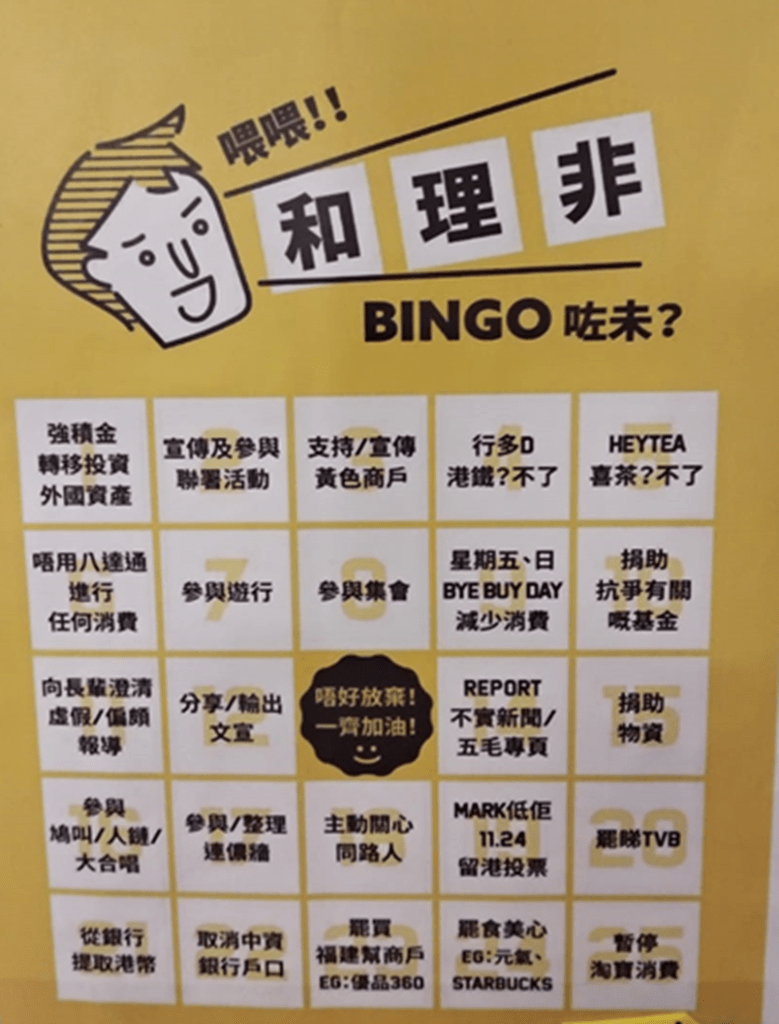

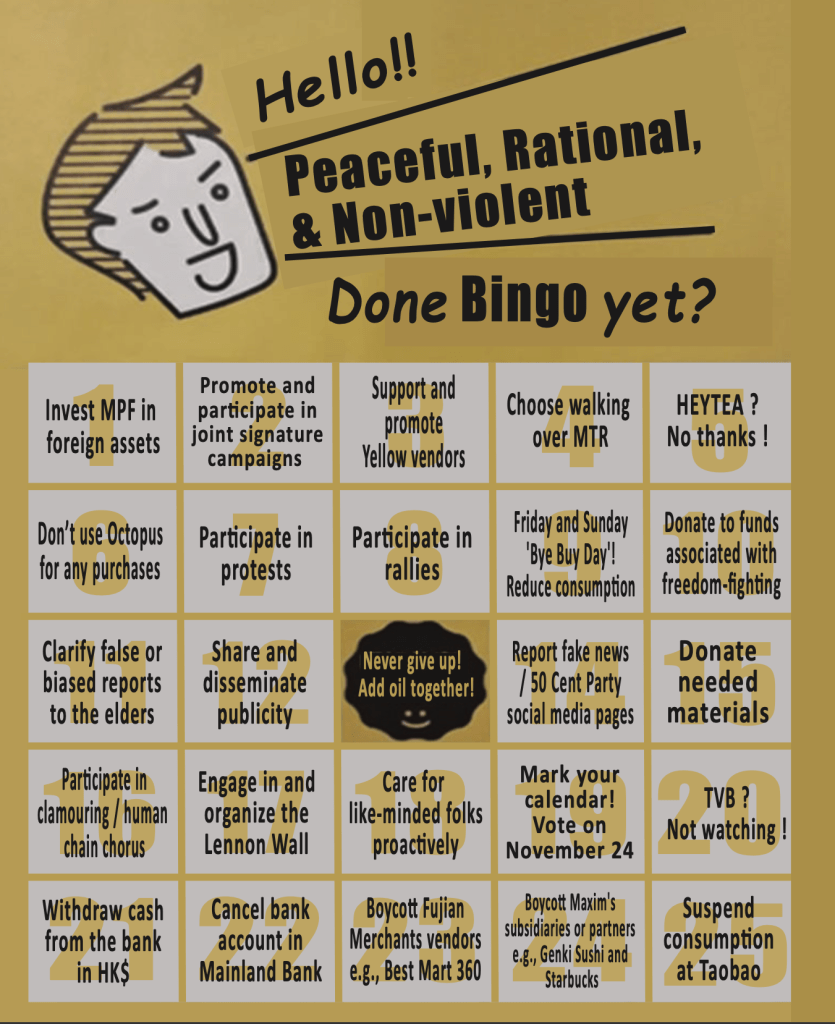

Protesters were not bound to a single mode of participation; individuals could engage in peaceful, disruptive (the most prevalent form in 2019), or violent actions. I recall seeing a “Protest Bingo” poster (see the original version in Chinese and its English translation below) that offered a range of participatory options, from frontline engagement to indirect contributions—for instance, I once provided brief translation assistance for international media. This gamified approach lowered the barrier for participation and encouraged even more reserved supporters to play a role.

Ho contends that the “growing reliance on violent means marked the marginalisation of the movement, not its strength”—a sentiment I share, especially considering that violent incidents constituted a relatively small portion of the protest actions when viewed in aggregate. Interestingly, this rise in militancy did not appear to diminish public support for the broader movement, as evidenced by the resounding turnout in the District Council elections that November.

Ho also explores what he terms “the power of the main stage”. While the 2019 protests are frequently characterised as “leaderless”, there was, in practice, a degree of coordination—various organisations played distinct roles throughout the course of the movement. Notably, groups and veteran activists who had been prominent in earlier protest waves found themselves somewhat marginalised, perceived as ineffectual in advancing Hong Kong’s democratic aspirations.

Perhaps the pivotal section of the book is Chapter 4, “Performing a New Community”. Devoted to the theme of “collective improvisation”—a “new community” acting in solidarity to facilitate communication—this concept was a hallmark of the Umbrella Movement in 2014, which attracted global attention. For instance, rail tickets and items of clothing were left in public spaces to assist protesters returning home after participating in actions. The community’s sense of belonging is encapsulated in expressions such as “hands & feet” (手足, sau2 zuk1), used to refer to the broad base of protest supporters, and sustained through declarations and solidarity slogans. The poignant slogan containing the word “revolution”—the representative phrase of the protest—should not necessarily be interpreted as advocating for secession from China. Rather, it may be understood more broadly, in the sense of the adjective “revolutionary”, denoting something ground-breaking or innovative.

The geographical dispersion of protest sites contributed to a “citywide unity of protests”, exemplified by communal sing-alongs of the protest anthem “Glory to Hong Kong” (notably, Ho omits mention of this anthem’s inclusion of phrases echoing the official national anthem). Songs, declarations, and visual imagery circulated across online platforms further reinforced the sense of a community bound by a shared destiny.

Chapter 5, “Global Fronts”, shifts focus to Hong Kong’s position as a “first-class world city” and the broader context of Sino-American geopolitical rivalry. Hongkongers responded with remarkable agility, improvising forms of support from abroad. The chapter examines how they re-engaged with local activism, mobilised resources for the movement, and lobbied host governments. In this way, global diasporic communities emerged, actively contributing to the protest cause beyond the city’s borders.

It was Covid-19 and the enactment of the National Security Law that effectively “froze” the fluid, improvisational character of the protests—what had come to be known as the “be water” ethos. Chapter 6, “Postmobilization Activism”, explores how activism was redirected towards opposition to pandemic-related restrictions, the development of a “pro-democracy” (colloquially referred to as “yellow”) economy, and support for imprisoned activists, community newspapers, and independent bookstores as a means of sustaining participation. Ho asserts that these activities “show how they minimised the harms brought about by political repression”; I remain somewhat unconvinced by this claim. One might more plausibly suggest that such actions represent an attempt to make the best of a deteriorating situation.

The book does not appear to employ the term “soft resistance”—now a central concern of the government, which encourages citizens to tell “good stories” of Hong Kong. In response, alternative media outlets were established, independent bookstores opened, and various forms of “everyday resistance” emerged. The notion of “blending protest into [everyday] life” persists, albeit in increasingly subdued forms—as reflected in what little remains of the independent press.

The book concludes with a discussion of “the art of surviving the repression” and contemplates the possible future trajectories of Hong Kong’s opposition movement, drawing parallels with Taiwan’s independence movement and the post-Tiananmen overseas Chinese diaspora. Yet I would caution against any certainty regarding this future path. Based on personal observation, this form of “underground” resistance may well persist, becoming even more discreet as “soft resistance” becomes the target of intensified official scrutiny aimed at neutralising dissenting voices.

This publication offers a comprehensive and methodologically rigorous account of the events of 2019, as well as their broader historical and political contexts. It also provides a valuable framework for the study and classification of other significant protest movements. As such, it is a welcome and timely contribution to the growing body of scholarship on the 2019 protests.

“Protest Bingo”, trans. Simon Ho

Header image: A photograph by Jennifer Eagleton, captured several years ago at the foot of the Goddess of Democracy statue at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

How to cite: Eagleton, Jennifer. “Improvising Revolution: Hong Kong’s Protests Through the Lens of Ming-sho Ho.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 29 Jun. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/06/29/be-water.

Jennifer Eagleton, a Hong Kong resident since October 1997, is a close observer of Hong Kong society and politics. Jennifer has written for Hong Kong Free Press, Mekong Review, and Education about Asia. Her first book is Discursive Change in Hong Kong (Rowman & Littlefield, 2022) and she is currently writing another book on Hong Kong political discourse for Palgrave MacMillan. Her poetry has appeared in Voice & Verse Poetry Magazine, People, Pandemic & ####### (Verve Poetry Press, 2020), and Making Space: A Collection of Writing and Art (Cart Noodles Press, 2023). A past president of the Hong Kong Women in Publishing Society, Jennifer teaches and researches part-time at a number of universities in Hong Kong. Her latest book is Hong Kong’s Second Return to China: A Critical Discourse Study of the National Security Law and its Aftermath (Palgrave, 2025). [All contributions by Jennifer Eagleton.]