📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

Masaki Kobayashi (director), Kwaidan, 1964. 175 min.

Ma—a profound Japanese concept that encapsulates the essence of stillness. The term refers to the empty spaces in between, a fleeting suspension in time, a purposeful pause in conversation. Ma is a vital thread woven into the fabric of everyday life in Japan, an articulation of absence that lends meaning to presence. Kwaidan (1964) embodies ma in its retelling of four haunting tales from Japanese folklore. Directed by the esteemed Masaki Kobayashi, Kwaidan is widely regarded as one of the finest anthology horror films ever created. It was awarded the Special Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival in 1965 and remains celebrated for its avant-garde set design and groundbreaking use of sound. Prior to his first colour film, Kwaidan, Kobayashi had reached a critical zenith with his epic war trilogy The Human Condition (1959–1961) and the acclaimed Harakiri (1962).

Tsugumo Hanshiro, a masterless samurai draws his sword as battle ensues in Harakiri (1962). Via.

“All of my pictures… are concerned with resisting entrenched power…”

Masaki Kobayashi was renowned for his unflinching depictions of war—portraying it not as an arena for heroism, but as a realm of terror and devastation. As a veteran himself, he eschewed the glorification of valour, choosing instead to expose the brutality and psychological torment endured by the Japanese people—a true horror in its own right.

The essence of horror cinema lies in its capacity to provoke dread through the suggestion of the incomprehensible, unsettling its audience with the eerie presence of the uncanny. Horror, in its visual language, is not intended to mesmerise, but to repel—to make one avert one’s gaze from what is too grotesque to bear. And yet, Kobayashi’s Kwaidan achieves something extraordinary while remaining firmly within the boundaries of the genre: it subverts expectation with grace. Through the use of exquisite colour palettes, avant-garde set designs, and an aesthetic sensibility reminiscent of the Edo period, Kobayashi constructs a film that defies the conventional grammar of horror. He conjures not fear through shock, but a sense of unease through beauty—a trance-like nostalgia that is both enchanting and disquieting. Kwaidan does not conform to the notion that horror must be transgressive or driven by jarring visual tropes; rather, it offers a hauntingly serene visual sanctuary that unsettles precisely because it is so arresting to behold.

Kwaidan opens with the first folktale-inspired adaptation—The Black Hair. The film begins with a slow pan through the shadowed corridors of a modest, timeworn home, where a disillusioned samurai is seen abandoning his wife, unmoved by her desperate pleas. Weary of a life mired in poverty, he resolves to wed a wealthy noblewoman and relocate to Kyoto. As the years slip by, an omniscient narrator charts the hollow trajectory of the samurai’s existence—one marked by discontent and haunted by recollections of the quiet, devoted life he once shared. Eventually, burdened by remorse, he returns to find his former wife waiting, arms open in forgiveness.

The wife grooms her long black hair in The Black Hair (1964). Via.

Kobayashi’s adaptation centres on a motif emblematic of vengeful female spirits in Japanese folklore—long black hair—and renders it a palpable, ominous force of vengeance. Upon reuniting with his wife after decades, the samurai exclaims, “Oh! How I missed your long black hair,” as she responds with a demure smile. This moment underscores a hollow longing—a desire perhaps never fully realised. After spending a night in her devoted embrace, the samurai awakens the next morning, still dazed, to a grotesque revelation: the decayed remains of his wife. Her long black hair, now a malevolent living entity, slithers toward him in a chilling manifestation of retribution.

One of the most distinctive features of this episode lies in the symphony of silence and sound. These opposing forces entwine through ma, conjuring a deeply unsettling atmosphere. The eerily dissonant score by Tōru Takemitsu employs the absence of sound as a compositional element, shaping the film’s singular tone. Rather than aligning sound with on-screen action, Takemitsu deliberately spaces auditory effects to evoke a jarring sense of anticipation. A striking instance of this technique occurs when the samurai crashes through a rotting screen—the corresponding sound delayed by several seconds, followed by an oppressive silence. As he scrambles to flee the crumbling house, weighed down by his own decaying body, the extended silence transforms the scene into a nightmarish choreography of despair.

The terrified samurai clings to his dear life as his wife’s vengeful spirit creates havoc in their home in The Black Hair (1962). Via.

Masaki Kobayashi introduces the second segment of Kwaidan with perhaps his most visually arresting narrative—The Woman of the Snow. Set against the ephemeral beauty of traditional Japanese art, the tale reimagines the well-known urban legend of the snow woman—Yuki-onna. The camera follows two woodcutters as they struggle through a relentless blizzard, its severity offset by a sky awash with radiant, painterly hues. Hand-painted sets, inspired by classical Japanese aesthetics, make this segment a captivating visual experience; from children running into the sunset to the mesmerising tapestry of the sky, The Woman of the Snow continues to be celebrated as one of the most visually exquisite films ever made.

Minokichi makes his way through the blizzard in The Woman of the Snow (1962). Via.

Two-dimensional in nature, these artistic compositions evoke an uncanny atmosphere—a liminal space. As an ominous instrumental tone swells in the background, the stage is set for a tale of quiet terror. Kobayashi’s experimental vision is most evident in his set design, particularly in The Woman of the Snow, where he conjures a metaphorical sense of doom through expressive eyes in the night sky, cast adrift by sweeping winds and falling snow. A visually arresting scene unfolds, underscored by a foreboding score that deepens its unease.

As the two men seek refuge for the night in a dilapidated shack, shielded from the raging blizzard, a spectral woman enters—possessing an otherworldly beauty, with skin as pale as the snow descending from the heavens. She glides towards the elder woodcutter and, with a single breath, freezes him in place, delivering the exquisite stillness of death. The younger, Minokichi, is spared—on the solemn condition that he never speaks of her ghostly presence.

Minokichi staring at the snow woman in a tantric daze in The Woman of the Snow (1962). Via.

What makes The Woman of the Snow stand out in such a meticulously crafted film is its measured, slow-paced suspense in harmony with the film’s striking aesthetic. Kwaidan was shot almost entirely on constructed sets, allowing Kobayashi full command over the visual composition. Clearly, he did not strive for realism, but rather for a gorgeously stylised homage to the folklore of an ancient Japan. Undeniably, Kwaidan is a visually stunning film—its beauty lies in the very impossibility of encountering such imagery in real life, rendering the film’s supernatural elements all the more elusive and mysterious.

A year passes in the tale of The Woman of the Snow; young and handsome, Minokichi resumes his work in the forest, his modest life unfolding beside his ageing mother. One tranquil summer evening, as the setting sun bathes the sky in an ombré of warm hues—rendered through exquisite watercolour-inspired sets—Minokichi encounters an enchanting young woman. Ten years pass in blissful marriage, as Minokichi cherishes a peaceful life with the beautiful stranger he once met.

Then, on a snowy night, he yields to the desire to speak of the snow woman to his wife. The warm, cosy home transforms into a chilling, hostile space as his wife’s once-gentle gaze hardens into a terrifying stare. In a cruel twist of fate, she is revealed to be none other than the enigmatic snow woman. Yet unlike the previous segment—where the samurai is physically destroyed by his wife’s spectral vengeance—retribution here takes the form of psychological torment. Minokichi is left standing on the verandah, abandoned and weeping with remorse, as the snow woman vanishes into the night sky—her eyes bearing the same ethereal intensity as the day he first beheld her.

The snow woman runs into the sinister night never to be seen again in The Woman of the Snow (1962). Via.

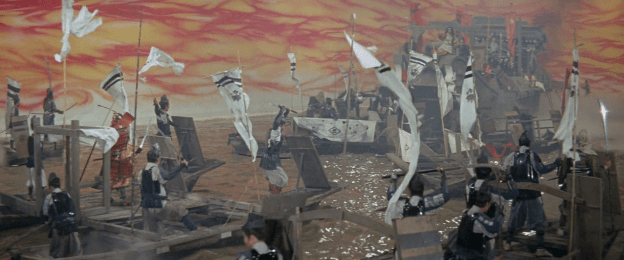

Enriched with historical and political resonance, Kobayashi’s rendition of Hoichi the Earless emerges as the next folkloric tale in the film. Rooted in traditional Japanese aesthetics, this particular segment of Kwaidan engages with culturally significant events from Japan’s past. Kobayashi conjures a liminal third space to parallel the supernatural, using mise-en-scène and expansive long shots to construct an alternate reality.

Filmed in an aeroplane hangar, Kwaidan allowed Masaki Kobayashi to exercise meticulous control over the visual environment, employing precise colour schemes that elevate the film’s aesthetic storytelling. This effect is realised through the use of painted cycloramas inspired by classical Japanese art—particularly emaki scrolls—merging a static, stylised pictorial tradition with the dynamic movement of live-action cinema.

A still recounting the epic battle of Dan-no-nura in Hoichi the Earless (1962). Via.

The cinematography and sound design in Hoichi the Earless draw heavily from the traditions of Japanese kabuki theatre. Lavish set design and a pronounced theatricality emanate from a classical screenplay that also bears the influence of noh drama. This folkloric tale is steeped in the religious and political sensibilities of a bygone Japan. Set within a Buddhist temple, the narrative follows the blind Hoichi—a biwa1 player by profession—who performs the mournful strains of The Tale of the Heike, recounting the epic Battle of Dan-no-ura. One starry night, the haunting melody of his lute summons a spectral samurai from the past, who requests that Hoichi perform for his lord. Guided to a mysterious court surrounded by noble figures, Hoichi sings his mesmerising tale—only to be summoned once more the following evening.

The temple priests, noticing Hoichi’s unexplained absences, follow him and uncover a disturbing truth: Hoichi has been lured by the restless spirits of the Taira clan, who perished in the historic battle. Unbeknownst to him, he has been performing atop the grave of Emperor Antoku, deep within a cemetery. These scenes, in which Hoichi sings for the ghosts, unfold within an opulently constructed set—sumptuously designed, capturing the ethereal beauty of a bygone era. Extravagant costumes and commanding performances lend the sequence an eerie magnificence. Kobayashi’s use of drifting fog conjures a spectral atmosphere—not unlike the watchful eyes in The Woman of the Snow—building a slow, chilling sense of dread as it creeps into the frame, foreshadowing tragedy.

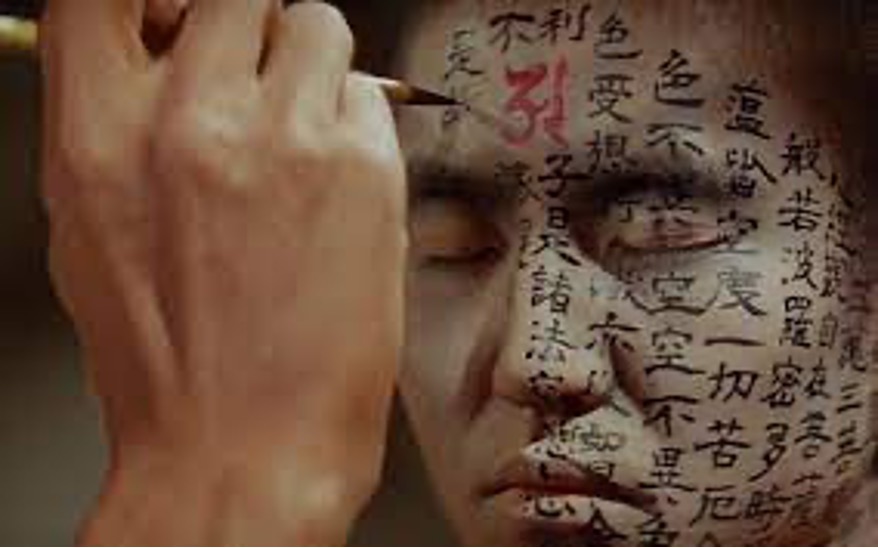

Realising that Hoichi has fallen under the spirits’ enchantment and faces imminent death, the priests turn to the power of ancient sutras to sever their hold on him. Kobayashi’s treatment of this climactic moment is rendered with reverent precision—offering the audience one of the most visually arresting tableaux in Kwaidan.

The priests inscribing the Heart Sutra on Hoichi’s face in Hoichi the Earless (1962). Via.

The temple priest instructs his acolytes to inscribe the Heart Sutra—a powerful spiritual mantra—all over Hoichi’s body, rendering him invisible to the spirits. The kanji inscriptions that adorn his skin evoke a haunting visual—one that fuses religious devotion with a sense of mounting dread. As the ghostly samurai returns to claim Hoichi once more, the blind musician remains silent, his entire form concealed and protected by the sutras—save for his ears. In a grotesque ritual, the samurai tears Hoichi’s ears from his head, believing he has fulfilled his lord’s command to summon the biwa player.

Yet this tale takes an unexpected turn: the darkness that befalls Hoichi ultimately alters his fate, leading him to become a wealthy and celebrated man. Hoichi the Earless offers the audience a comparatively redemptive conclusion—markedly different from the grim destinies met by the characters in the other segments of Kwaidan. It gestures towards a moral thread of fate that weaves through Hoichi’s story: though not unscathed, he emerges from terror into prosperity.

The fourth and final segment of Masaki Kobayashi’s Kwaidan is steeped in ambiguity. Distinct from the earlier, more overtly chilling tales, In a Cup of Tea eschews sound effects, visual spectacle, and elaborate theatrics. Instead, it embraces a narrative form that would later be recognised as psychological horror. The story unfolds as a tale within a tale—the shortest in the entire anthology—yet it draws the viewer into a labyrinth of thought, where the boundaries between fiction and reality quietly dissolve.

A mysterious reflection staring back at the night guard in In a Tea Cup (1962). Via.

The story begins with a writer who pens an enigmatic tale—one that recounts the bizarre experience of a night guard haunted by a mysterious reflection in his cup of tea. As the boundary between dream and reality dissolves, the protagonist of the writer’s story finds himself teetering on the edge of madness, battling invisible forces. The tale concludes without resolution—no climax, no ending—leaving the viewer unsettled and searching for meaning.

The narrative then shifts back to the writer’s world, where his publisher arrives in search of him. At the outset of the segment, an omniscient narrator remarked that many Japanese folktales remain unfinished—whether abandoned out of disinterest or halted by the sudden death of their authors remains unknown. As the film nears its end, this observation takes on an uncanny resonance. The publisher’s frantic search becomes a meta-commentary, echoing the narrator’s words, as the writer himself seems to have vanished—transformed, in an ironic twist, into the very apparition he once imagined: an illusion in a teacup.

What is most compelling about this final segment is that its interpretation lies entirely in the hands of the viewer—whether as a metafictional coda to the anthology or as yet another folkloric fragment, glimmering with moral ambiguity. Its enigmatic quality distinguishes it from the other tales, marking a deliberate shift into psychological introspection.

Masaki Kobayashi’s Kwaidan endures as a rich tapestry of cultural and artistic expression. Each segment, inspired by Lafcadio Hearn’s Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things, weaves supernatural intrigue with deeply reverent aesthetic techniques. The film has withstood the test of time and remains a seminal work—an enduring pioneer in the canon of Japanese horror.

How to cite: Gogoi, Tushi. “Kwaidan: Horror and Folklore as an Art Form.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 16 Jun. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/06/16/kwaidan.

A writer with a passion for storytelling, Tushi Gogoi is currently experimenting with different genres of writing. Her primary interest lies in narrative fiction—with a particular fascination for the horror genre. She has engaged in multiple research projects, most notably her thesis, “The Study of the Influence of Folklore on the Evolution of Japanese Horror Films,” which has significantly shaped her understanding of folklore’s impact on storytelling. Through both research and creative writing, she continues to explore the depths of horror and its evolving narratives. [All contributions by Tushi Gogoi.]

- A Japanese short-necked wooden lute used for narrative storytelling. ↩︎