📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

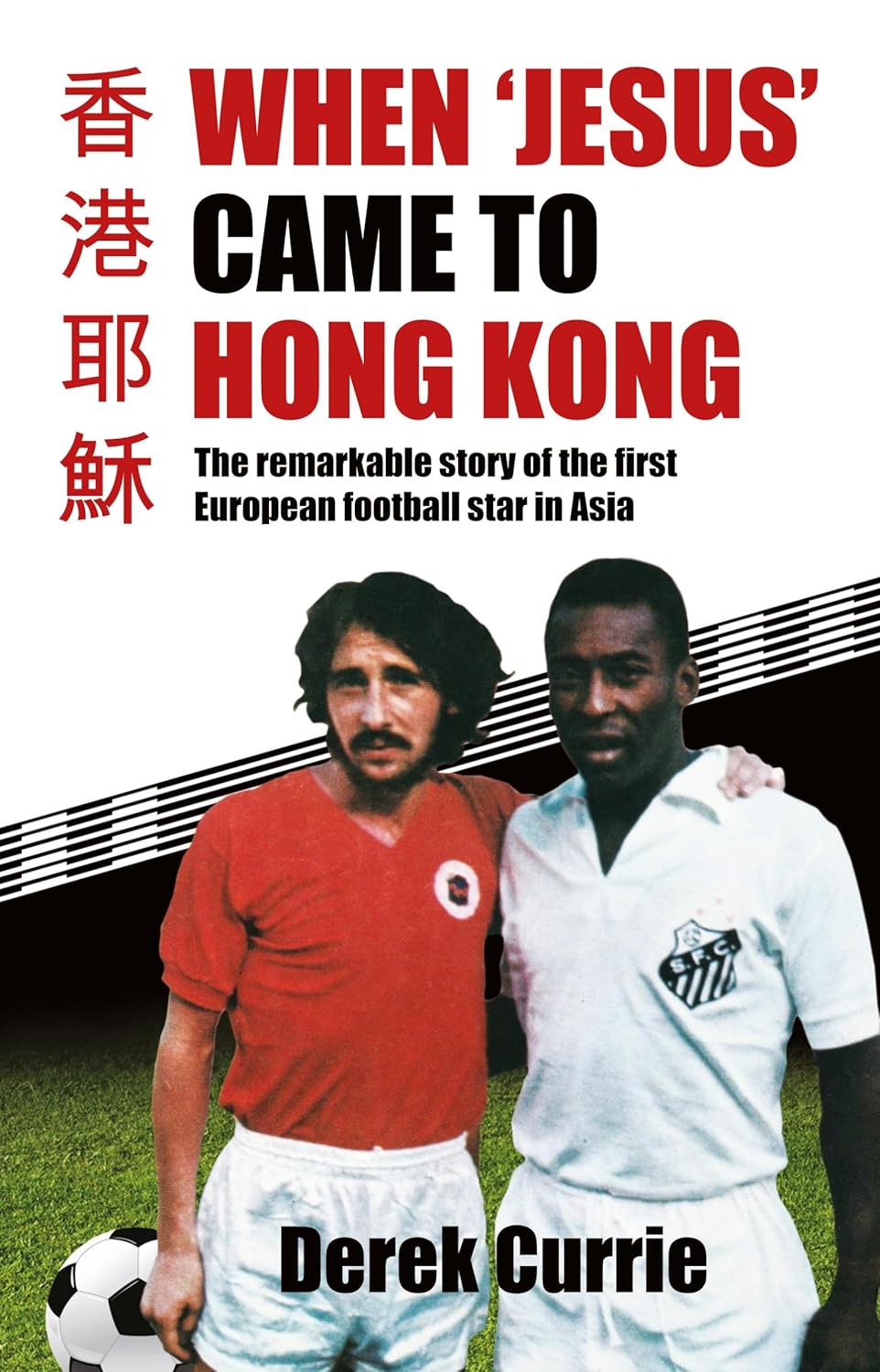

Derek Currie, When ‘Jesus’ Came to Hong Kong: The Remarkable Story of the First European Football Star in Asia, Blacksmith Books, 2023. 404 pgs.

This is my second review of a first-person narrative chronicling the pursuit of a career in Hong Kong during the twentieth century. The first, Rob Noble’s account of his creation of the Octopus card, centres on a book that prioritises the object over the individual. It is concerned almost entirely with the technical and commercial dimensions of the card, offering scant insight into the author himself.

This book adopts a markedly different approach. Written by Derek Currie—well known among late twentieth-century Hong Kongers as the face of local football and of Carlsberg beer—it focuses on football, and, to a certain extent, himself. Currie recounts much, though noticeably omits his private life and inner reflections. It is a collection of anecdotes one might hear in a pub, rather than a conventional autobiography.

I first became aware of the Hong Kong national football team when its junior squad faced Indonesia’s sometime in the mid-1990s. I was struck by the presence of several European faces among the Hong Kong players. As it turned out, by that time it was not uncommon for Hong Kong to recruit residents of diverse racial backgrounds into its national teams, irrespective of their birthplace. Three decades on, even the Indonesian national team features players born in Europe.

1970s: The Footballer

◯

Currie was not the first European to play football in Asia, but he was the first to attain stardom—largely because he began much earlier than most, at the age of 21 in 1970. The book opens with his family’s relocation from inner Glasgow to the newly developed district of Carnhill. By the age of 18, he was playing for one of Scotland’s top clubs, Motherwell, where his speed and agility as a winger-forward drew attention from their wealthier rivals, Rangers—a development that unsettled his coach once the rumours began to circulate.

While his brother John would go on to play part-time for Glasgow Rangers, Derek departed Motherwell for Rangers as well—though in his case, it was the Hong Kong Rangers. Ian Petrie, a fellow Glaswegian, had moved to Hong Kong in 1958 to work for the Taikoo Dockyard and Engineering Company, a Swire Group enterprise that operated until the early 1970s, when it was merged into the Hong Kong United Dockyard. Petrie established a football club named after his favourite team, and by the 1960s, it had earned a reputation as a breeding ground for young talent, though it often struggled against more formidable opponents.

Petrie’s solution was to bring in Scotland’s young footballers. But why, in an era before affordable international calls, satellite television, or personalised in-flight entertainment, would these young men choose to journey halfway across the world? For Currie, it was the tantalising promise that—should he prove himself—he might face Pelé by year’s end.

It was not that Rangers would play against the Brazilian national team, but rather that Pelé (Edson Arantes do Nascimento), who had reasserted his status as the world’s finest footballer during the 1970 FIFA World Cup in Mexico, would be visiting Hong Kong with his club, Santos. Their opponents would be Hong Kong XI—an all-star team comprising the best players from the Hong Kong First Division League.

Derek Currie faced a choice: to pursue a career in the Scottish Football League—with the future prospect of national team selection and the opportunity to play in Europe—or to place his faith in himself and in Petrie, and move to a place he knew only from The World of Suzie Wong. He chose Suzie Wong—or more precisely, the chance to face Pelé.

Joining him were Walter Gerrard and Jackie Trainer, two other young Scotsmen. The flight to Hong Kong took twenty hours, routing through Beirut and Bangkok, and culminated in the dramatic approach to Kai Tak Airport via the Checkerboard Hill waypoint, where the pilot had to execute a 47-degree turn at 200 miles per hour above residential buildings before landing.

Then the challenges began. Rangers had ostensibly been relegated from the First Division, but the league was subsequently expanded, and Petrie fought all the way to the courts to keep the team in. Currie was introduced to the Hong Kong press as a “George Best type”—a reference to the quick, charismatic Manchester United forward, known for his long hair and distinctive facial hair. His first breakfast in Hong Kong was not the bacon and eggs he longed for, but yum cha with the local players.

At 21, as the first professional European footballer in Hong Kong, Currie proved good enough to earn a place in the Hong Kong XI. On 8 November 1970, the team defeated Swedish club Djurgårdens, thanks to his decisive goal. The following day, fans hung a banner in Chinese that read, “Jesus saves Hong Kong”—and his nickname was born. Newspaper cartoons during the visit of Pope Paul VI to Hong Kong—still the only papal visit to the city to date—further popularised Currie’s image as a football-playing Christ figure in Hong Kong.

As promised, he faced Santos and Pelé, exchanged shirts with the Brazilian legend after the match, and their photograph together now graces the cover of this book. And that is the life he recounts within its pages—playing league football and touring Southeast Asia with his clubs; joining the Hong Kong XI and meeting some of the greatest figures in world football; socialising with British and Australian expatriates at the horse races. Apart from the unnerving episode of encountering a snake in his bedroom during a tropical storm, there is little personal reflection—nothing of how he formed relationships or navigated the emotional vicissitudes of life.

In 1972, Currie joined Seiko—a club owned by the Wong brothers, who manufactured watches for Japan’s Seiko. By the mid-1970s, he had arguably become the most recognisable and well-liked white man in Hong Kong, appearing in advertisements for Bell’s whisky and the highly successful Keep Hong Kong Clean campaign, as well as writing and commentating on international football for The Star tabloid and Radio Television Hong Kong.

In 1975, difficulties in his first marriage (he does not so much as mention the wedding) led him to accept a loan move to the United States, where he played for San Antonio Thunder in the extravagant North American Soccer League, reuniting with Pelé and other global icons. In 1979, he became the first European—and the first professional footballer—to play for the Hong Kong national team, scoring a solitary goal against Sri Lanka.

He retired in February 1982 at the age of 33. For his final match, he greeted his neighbour Anita Mui and walked from his Paterson Street flat to Caroline Hill Stadium, where the Hong Kong XI faced Stuttgart of West Germany.

The 1980s: The Carlsberg Man

◯

The second act of his life unfolds after football. He appeared as an extra in three films: Bruce Lee in New Guinea, a Bruceploitation production; The Head Hunter (1982), alongside Chow Yun-fat and Rosamund Kwan; and All the Wrong Spies (1983), a Second World War comedy starring George Lam and Brigitte Lin.

His primary occupation following retirement was as a public relations manager for Carlsberg—a role closely intertwined with football and other sports, given the Danish brewery’s significant investment in sporting sponsorship across Europe and Asia. In Hong Kong, this encompassed football, horse racing, and various forms of rugby.

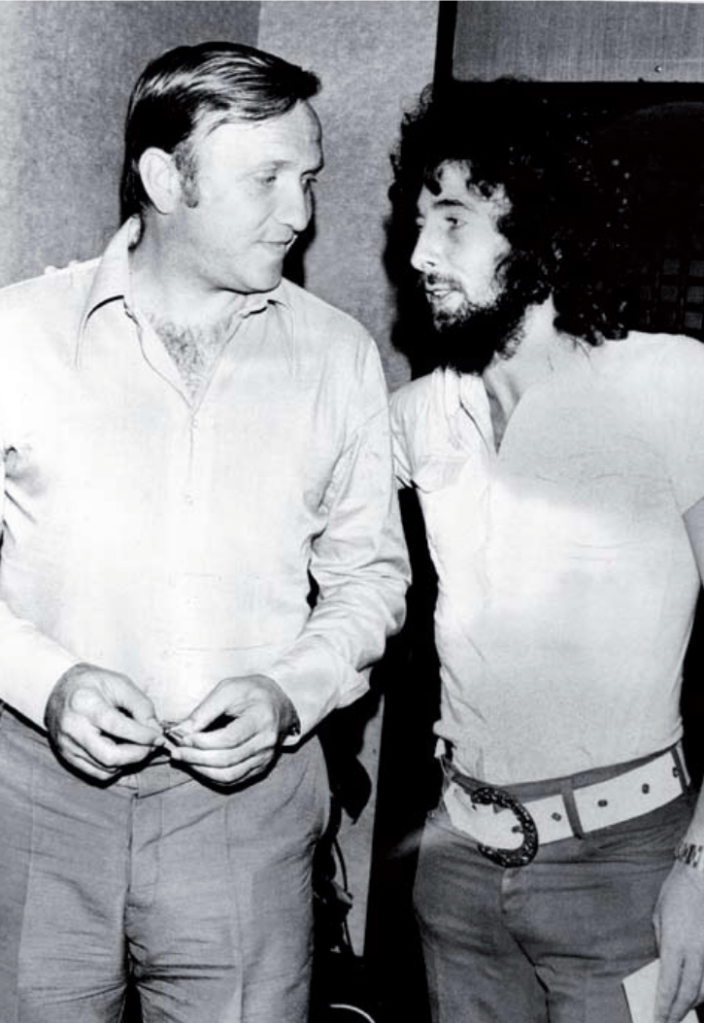

The Lunar New Year Cup was branded the Carlsberg Cup from 1986 to 1989, and again from 1993 to 2006. During this time, Currie encountered numerous international footballers and dignitaries attending the tournament, from Prince Joachim of Denmark to a young Danish goalkeeper named Peter Schmeichel, whom he famously took to Hong Kong’s first McDonald’s, on Paterson Street. Years later, Currie repaid the gesture by having Schmeichel—by then a world-renowned goalkeeper—draw the lots for the Carlsberg Cup in Manchester, England.

The PR crises he recounts are, in hindsight, more amusing than alarming—such as the scramble to retrieve kegs mistakenly filled with potent Special Brew across Hong Kong Island and the Kowloon Peninsula, or managing the turbulence of the 2003 Carlsberg Cup final between the volatile teams of Iran and Uruguay.

The final section of the book covers his adventures across Europe and North America as a World Cup and European Championship reporter for The Standard and Oriental Daily News (including the short-lived English-language edition, Eastern Express), all under the sponsorship of Carlsberg. The narrative concludes with his explanation to a Scottish journalist of how he has achieved the “Hong Kong Dream”: he owns a lawnmower—an emblem of rare domestic space in a city where, as he wryly notes, only 2% of the population do not live in flats.

Rather than a conventional autobiography, this volume offers a series of pub tales—vignettes from the lively and often exhilarating life of Derek Currie. He offers little commentary on twenty-first-century Hong Kong or the current state of its football. Such concerns lie beyond his interests, and the recollections of former colleagues in the opening pages evoke a golden age—a “melting pot” era in 1970s and 1980s Hong Kong, “when East and West met.” Regardless of his intended audience, the book serves as a valuable chronicle of life in Hong Kong during that period.

A more coherent autobiographical structure might have served the work to better effect. I also wish Currie had explored the development of Hong Kong football following his retirement as a player, particularly during the final years of the colonial era up to 1997. The 2–1 victory over China on 19 May 1985 remains a significant milestone in the city’s footballing history, even if fans across the border may interpret it differently.

Hong Kong’s return to the Asian Cup after 56 years—in 2023, the year of this book’s publication—could have offered a fitting epilogue, especially had Currie chosen to situate himself within that moment, as he so often does throughout the text, whether as commentator or spectator. That would have made for an excellent pub tale.

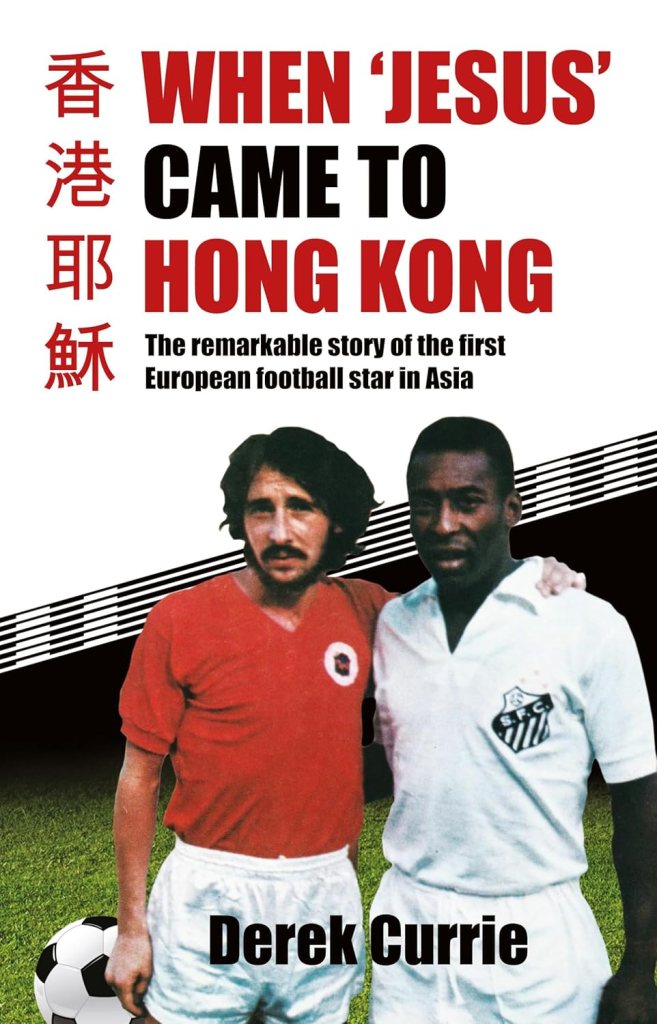

With the great Santamaria of Real Madrid at the Lee Gardens Hotel when he visited as manager of Barcelona side Espanyol.

Making the draw at Old Trafford with “Great Dane” Peter Schmeichel.

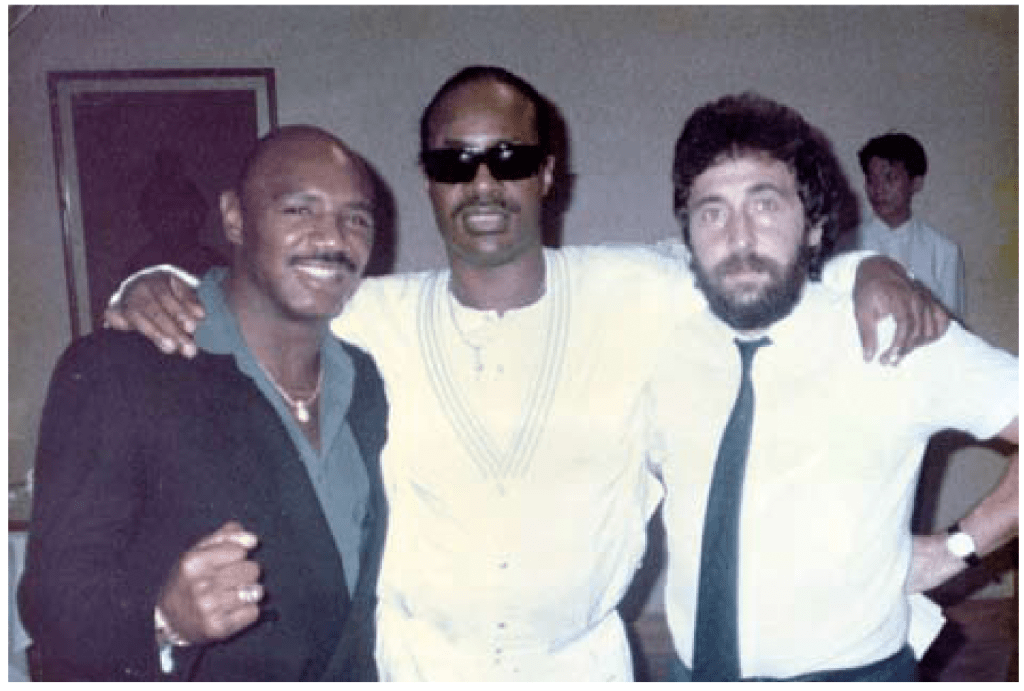

“I just called to say I love you,” Derek Currie (right) with Marvelous and Stevie Wonder before they sang at the Hong Kong Hotel.

How to cite: Rustan, Mario. “Jesus’ Pub Tales: Derek Currie’s When ‘Jesus’ Came to Hong Kong.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 16 Jun. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/06/16/jesus.

Mario Rustan is a writer and reviewer living in Bandung, Indonesia. [All contributions by Mario Rustan.]