📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

Kim Ki-duk (director), The Isle, 2000. 90 min.

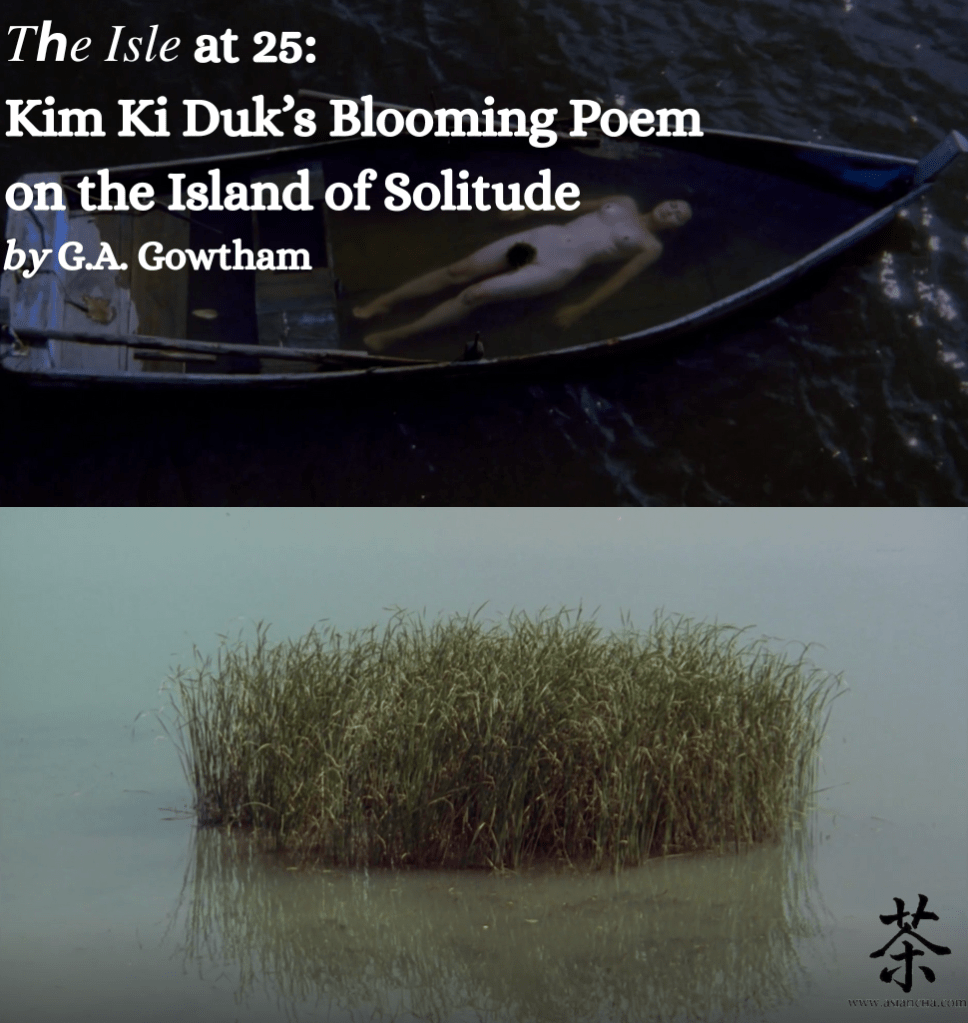

Some films are like waves that gently lap against the shores of our memories; others, however, jolt us by revealing the immensity concealed beneath the stillness of the deep sea—and, at times, its fury. The Isle (2000), by the controversial yet enigmatic Korean filmmaker Kim Ki-duk, is one such work.

As we mark the 25th anniversary of the film’s release, we also celebrate its poetic silences and hauntingly beautiful aesthetics. Yet the deeper questions it evokes merit revisiting. For cinephiles unfamiliar with Kim Ki-duk—especially those new to his distinctive cinematic universe—let this journey be akin to taking the hand of an accomplished critic, gently ushering one along the rugged paths of the lonely isle and its deep, melancholic waters.

The film is set upon a vast, tranquil lake, far removed from the clamour of the civilised world. Here, Hee-jin rents out floating shacks, providing food, bait worms, and at times, sexual services to the visiting anglers. In her isolated and emotionally numbed world, a significant shift occurs with the arrival of Hyun-shik—a fugitive seeking refuge from the law after committing a murder. There is little dialogue between the two; their relationship, much like the lake itself, is quiet, yet harbours unfathomable depths and latent danger.

The Isle eschews conventional storytelling, unfolding instead through evocative imagery and symbolic resonance—more akin to a poem than a traditional narrative. The lake becomes a mirror of Hee-jin’s solitude and the recesses of her inner self. At times serene and sublime, it can just as suddenly become volatile and unforgiving. The fishing bait is not merely a practical tool—it embodies the intricate dynamics of human connection, attraction, and suffering. Kim Ki-duk visualises these hooks and thorns as instruments that wound and entangle, ensnaring not only fish but human souls as well—a remarkable metaphor for pain, loss, and alienation, and a chilling reflection on the murky intersections of sex and death.

Each scene is composed like an eclectic painting. Cinematographer Hwang Seo-shik captures the beauty of nature with striking imagery: floating cottages, lakes shimmering in shifting shades of blue, the glistening of early morning dew, and the burnished hues of sunset. These scenes are not merely decorative—they mirror the emotional landscapes of the characters. The use of camera angles and extended takes often induces a meditative state; they immerse us in the environment and draw us into the emotional currents that run beneath the surface.

Dialogue in the film is sparse. As Hee-jin is mute, her emotions are conveyed entirely through facial expressions and bodily gestures. Hyun-shik, too, remains largely silent. This quietude does not suggest emptiness, but rather underscores the depth of unspoken feeling and the intuitive understanding between them. The ambient sounds of lapping waves, rustling wind, and birdsong serve as a more potent narrative device than any traditional score. At times, complete silence heightens the tension of a scene, amplifying its emotional resonance. Indeed, throughout The Isle—as in much of Kim Ki-duk’s oeuvre—the body becomes the principal instrument of expression. Emotions are articulated through physical pain, and the protagonists communicate through a visceral choreography of shared suffering and violence.

Upon its release, The Isle provoked controversy for its graphic, often unsettling depictions of violence—particularly those involving animals. Scenes such as a fish being cut alive, cooked, and consumed, or the beating of a frog, drew harsh criticism from viewers and animal rights activists alike. At the Venice Film Festival, some audience members reportedly walked out mid-screening, unable to endure the brutality portrayed on screen.

These scenes are not intended for the fainthearted, yet they cannot be dismissed as mere sensationalism or calculated shock. Rather, the director treats them as integral to the film’s narrative fabric—expressions of the characters’ emotional landscapes, their brutal passions, and their fraught, often violent relationship with the natural world. Far from glorifying such imagery, they ought to be seen as a desperate attempt to lay bare the decay of human connection, the clumsy pursuit of love, and humankind’s relentless domination over nature. Kim Ki-duk is an artist who strives to reveal the ugliness concealed within beauty—and, conversely, the strange beauty within ugliness.

Kim Ki-duk’s films frequently centre on society’s marginalised—neglected souls such as sex workers, criminals, and those cast into isolation. His characters rarely articulate their emotions through dialogue; rather, their stories unfold through actions and the visceral intensity of their experiences.

His cinema treads a fine line between the aesthetic and the violent. In Kim’s vision, beauty is not merely delicate—it can also be cruel, even shocking. His philosophy lies in fearlessly confronting the darkness and turmoil that reside within the human psyche. This ethos is vividly manifest in The Isle, where his unflinching gaze interrogates the harsh realities of Korean society and their impact on the individual.

Despite the polarised and impassioned reactions it provoked, The Isle garnered significant attention at international film festivals, and is now regarded as a key work in the “New Wave” of Korean cinema. Long before directors such as Bong Joon-ho (Parasite) and Park Chan-wook (Oldboy) brought Korean cinema into global mainstream consciousness, Kim Ki-duk was already commanding the attention of serious cinephiles with his singular, uncompromising vision. Eschewing the conventions of Western cinema, his films embraced Asian philosophies and explored the raw intensity of human emotion alongside the complex, often adversarial, relationship between man and nature. Kim Ki-duk remains a controversial—yet unquestionably influential—figure in contemporary cinema.

The Isle is neither merely a love story nor a tale of revenge. It is an experience—an artistic provocation, a challenge, a puzzle that unsettles, compels reflection, and at times, provokes discomfort or even revulsion. It was a bold attempt to capture fundamental human emotions—love, lust, jealousy, rage, loneliness, and longing—in their rawest form, stripped of pretence or moral cushioning. Kim Ki-duk, who is said to have drawn inspiration from the works of Austrian painter Egon Schiele, invites us to engage with the distinctive language of his visual expression and his unorthodox treatment of the human form.

The enduring power of a work of art lies in the impression it leaves upon its audience and the questions it continues to raise. Decades later, the impact of The Isle remains undiminished. Its singular aesthetics and the dilemmas it poses are still debated among cinephiles and critics alike. The film is now available on platforms such as the Internet Archive, offering a new generation the opportunity to encounter Kim Ki-duk’s essential and uncompromising vision.

A quarter of a century on, the desolate island of The Isle—with its silent tremors and cruel beauty—continues to hold an important and inescapable place in the topography of world cinema. Its pull, like a fine, barbed hook, tugs at our thoughts, drawing us into the darker depths of the human condition. It is not simply a film; it is an intense, poetic, and blood-soaked meditation on human existence—one that lingers, hauntingly, in the memory.

How to cite: Gowtham, G.A. “The Isle at 25: Kim Ki Duk’s Blooming Poem on the Island of Solitude.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 16 Jun. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/06/16/isle.

G.A. Gowtham is a film editor and writer based in Chennai, India. His professional experience in shaping narratives on screen profoundly informs his perspectives as both a writer and a literary translator (from English to Tamil). A keen observer of cinema, politics, and culture, his critical essays and reviews have appeared in esteemed Tamil publications such as The Hindu Tamil, Ananda Vikatan, and Kalachuvadu, as well as in English for ThePrint. Gowtham’s work often delves into the nuanced intersections between artistic expression and societal dynamics. Through his multifaceted engagement with storytelling—both visual and textual—he endeavours to cultivate a deeper understanding of contemporary art and its cultural significance. For further information on his work,please visit his website. [All contributions by G.A. Gowtham.]