Sudeep Sen and Jhilam Chattaraj

Jhilam Chattaraj’s note: I shall always remember that moist, sunlit afternoon. The venue—a lush tropical garden—was adorned with local blooms and talismanic touches, including multicoloured paper lanterns that swayed gently in the breeze, as though singing to the wind. It was here, at the Asia Pacific Writers and Translators Meet, held at Chiang Mai University, Thailand, on 22 November 2024, that a preview of my current book, Sudeep Sen: Reading, Writing, Teaching, took place.

The event marked a significant moment in celebrating forty years of writing by the internationally acclaimed poet, editor, translator, and artist, Sudeep Sen. His joyful and spirited participation lent the preview a special resonance and enduring warmth. Indyana Horobin of Griffith University, Australia, moderated the session. His thoughtful questions traced the origins of the book, probing the initial spark of curiosity that led to its creation.

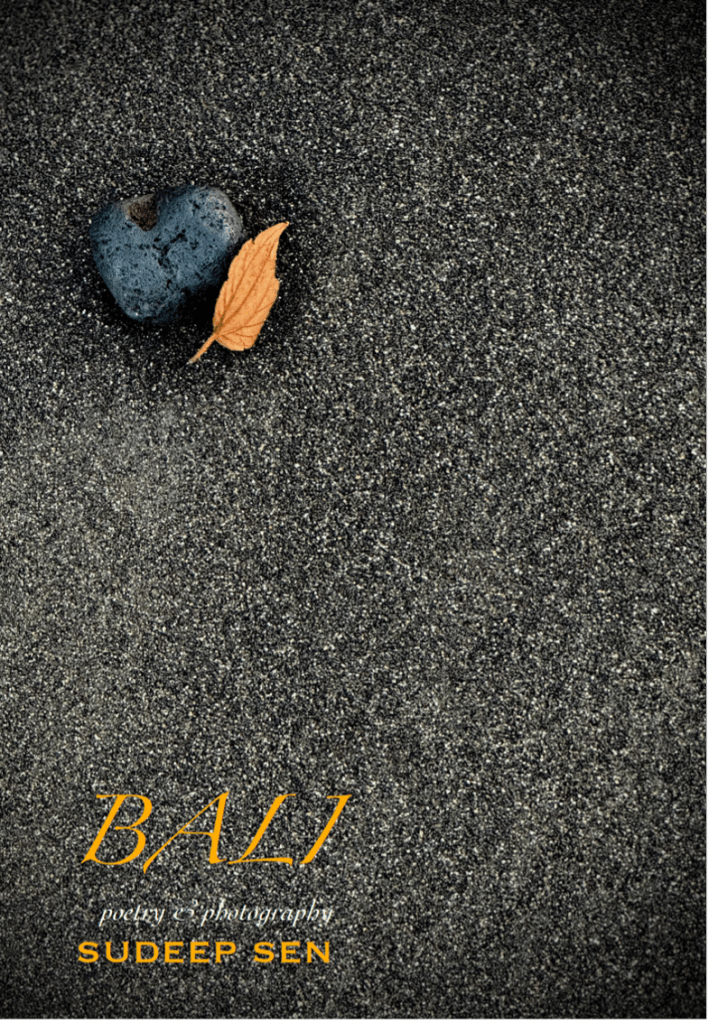

Sudeep Sen’s presence also allowed for a formal conversation about his recent work. In this interview, we explore his one-month stay in Bali; the lyrical and visual poems inspired by the black sands of Pacung, Northern Bali; the unexpected camaraderie with komodo dragons; and the therapeutic influence of aquatic life on his creative process. We also touch briefly on Sen’s writing about Chiang Mai and the exciting prospect of a poetry series dedicated to Southeast Asia.

Jhilam Chattaraj

Your journey to Bali began with the Singaraja Literary Festival (2024). How would you describe the experience?

Sudeep Sen

The Singaraja Literary Festival is now in its second edition. As a relatively new event, it hosted only a small number of international writers, which made for an intimate and engaging atmosphere. It was held in a less conventional part of Bali—Singaraja, which is not as tourist-driven as other regions of the island. It has a more residential, laid-back character.

The festival itself was thoroughly enjoyable. All of my sessions went smoothly. I also co-led a workshop with Filipino performance poet Nerissa Carmen, which proved to be a success. It was our first time meeting—an experience that can sometimes bring a degree of apprehension—but it turned out to be a very positive collaboration. She is a poet grounded in performance, while I take a more craft-oriented approach. As a result, we complemented each other remarkably well. I had a great deal of fun.

I also conducted a solo workshop, and the participants—some of whom were older than me—still keep in touch. It’s very touching.

Jhilam Chattaraj

Were you the only Indian writer?

Sudeep Sen

Yes, as it tends to be in most places and also, when I am travelling.

Jhilam Chattaraj

After that, you spent some time in Pacung, where you composed a significant number of poems. There is a palpable sense of calm, brightness, and a pristine clarity of mind in this body of work. Shades of white, yellow, and blue—evocative of tropical and volcanic landscapes—recur throughout, subtly conveying the influence of the sea and the quietude of your isolation.

Sudeep Sen

I’ve previously spoken about how my three-month residency at Nirox in South Africa was a life-changing experience. I thrive in silent, solitary spaces, and ever since that period, I’ve found it increasingly difficult to readjust to cosmopolitan life—regardless of location. Something within me has shifted, quite profoundly. In that sense, Bali served as an affirmation of my deep-seated affinity for quietude.

Jhilam Chattaraj

Have you always been this way? You’ve undertaken several residencies over the years, but would you say this yearning for solitude is a recent development—or has it always been present in some form?

Sudeep Sen

No, I’ve certainly enjoyed the company of other writers in the past. But the yearning to be alone has become more pronounced in recent years. Previously, my residencies typically lasted just a month. Since then, I’ve cut myself off from social media and distanced myself from many people—only to realise how little of it I actually need. It’s been liberating. I’m less informed in the conventional sense, and I now indulge only in a physical newspaper. The constant buzz of a digital newsfeed no longer holds my interest.

In Bali, the sun became my clock. I spent my days writing, conversing with the few people around me, and watching the stars. My friend Philip Cornwall Smith—a well-known writer and journalist specialising in South Asian culture—encouraged me to download an app that maps the skies and the tides. It employs sophisticated technology to connect us with nature in a completely different way. In big cities, you can’t even see the sky.

Everything I touched in Bali seemed to exist in a pristine state. The volcanic rocks were millions of years old—untouched, unobserved, and unaltered by human interaction.

Jhilam Chattaraj

You are also the first poet who has written about Pacung in poetry.

Sudeep Sen

Yes, absolutely. The beauty of Northern Bali is utterly captivating. The landscape is extraordinary—jet-black sands, moonscape-like volcanic rocks—and, in contrast, lush tropical greenery on the other side. Familiar vegetation such as mango trees, bougainvillaea, and frangipani flourished everywhere. The sky would shift so swiftly; I was completely absorbed in the theatre above. In moments like those, one realises that nothing else is needed.

Jhilam Chattaraj

Nothing else caught your attention, I guess.

Sudeep Sen

I found myself growing rather melancholic as the end approached. Normally, one looks forward to returning home—but I didn’t.

Jhilam Chattaraj

That’s quite surprising, given how naturally social you are. It’s hard to imagine you actively seeking complete solitude.

Sudeep Sen

That’s me. Suppose I receive an invitation to a dance performance—and I do love dance—there’s a part of me that doesn’t want to go, yet I also feel I’ll regret missing it. In Pacung, there were no opportunities to socialise in the way I’m accustomed to in Delhi. Restaurants, pubs, and clubs all close by 6 p.m. It’s a lifestyle not suited to everyone.

I know many writers who, after a week or so, would say, “Let’s head to the city, eat out at a restaurant, have a drink at a bar or café.” But I simply don’t feel the need. As long as I can spend 80 to 90 per cent of the year in such quiet, reflective spaces, I can manage the remaining 10 per cent in Delhi—because that is my reality. Still, something within me has shifted, and this trip has only affirmed that change.

Jhilam Chattaraj

The shift, perhaps, lies in a growing need for focused and intentional engagement with the environment.

Sudeep Sen

Yes, I do feel that the trees, rocks, sand, sea, water, and skies speak to me—I have a silent conversation with them. I’ve always felt connected to nature, but places like Nirox and Pacung have enabled me to explore that connection in a deeper, more meaningful way. And I don’t mean to suggest that I’ve become a spiritual person or a saint—only that this communion with the natural world has grown more profound.

Jhilam Chattaraj

It’s a different kind of spiritual shift—not one necessarily tied to an identifiable god or organised religion, but rather a quiet attunement to the natural world and its rhythms.

Sudeep Sen

The poems I wrote in Bali are, in a sense, an extension of those composed in Nirox. Bali, however, is much more rooted in ceremony, ritual, and an abundance of gods and goddesses. In that sense, it felt familiar—resonant with my Indian way of being. At the same time, there was comfort in the colour and ritual, and because I did not understand the language, I cannot claim with certainty that anything transcendental was being spoken. Perhaps it wasn’t—perhaps it was simply, “I want three extra goats for my farm,” or “my daughter needs to marry a wealthy boy.”

Yet their acts of ritual freed me from the constraints of human communication. The ritualistic performances resonated deeply with me. I came to realise how little one truly needs in life. At this point, all I require is my computer, camera, a fast internet connection—and, of course, food. The chef would catch fresh fish from the ocean, and I enjoyed it—not necessarily in a Bengali way, but simply grilled: healthy eating, with a bit of garlic, herbs, spices, and local sambal. It was exquisite.

Since returning, I find the vegetables here look almost fake—botoxed. In Bali, everything was so pure.

Jhilam Chattaraj

During your stay, was there a single moment that you’ll never forget—one that left a lasting impression?

Sudeep Sen

The majestic black sand and volcanic rocks—I’ll never forget them. I’ve seen black sand before, in Greece, but in Bali, I had the time to truly engage with it. I walked on it, collected it, and brought some back with me to Delhi. They’ve become like my children. It’s a beautiful thing—they nourish me in ways I can’t fully explain. Can you imagine the power of an inert rock?

Jhilam Chattaraj

Of course—you believe in them, and it’s through that belief that the connection has been forged.

Sudeep Sen

It was always there. In Delhi, opportunities to engage with nature in that way are rare, but much can still be achieved through immersive experiences. I prefer to remain in one place and truly get to know a country, rather than rush through the ten best sights. In Bali, I connected with the rocks—I photographed them: one day splashed by the sea, another day almost reclaimed by it. They were never the same, and I was able to capture that. I’ve carefully documented their shifting moods and traced their place within a broader galactic context. This is how I wish to remain—immersed in that world.

Jhilam Chattaraj

This stay seemed almost like a self-designed residency. In what ways did you meet your literary goals during that time?

Sudeep Sen

I have a very tactical approach to connecting with and staying in Pacung—80 per cent of the time, I follow a plan. Initially, I intended to use the time to respond to all my deadlines. But I found myself inspired every single day, so much so that I decided to write these poems instead—otherwise, they would have slipped away. The plan, in that sense, failed—but wonderfully so. Within a month, I had almost completed a manuscript for a new work. It was magical.

Jhilam Chattaraj

In what ways will your collection Rocks be informed or shaped by this experience?

Sudeep Sen

Yes, it will all be connected… Hampi, Hyderabad, volcanic rocks. I wish to see the rocks of the Arctic and Antarctica. I want to see ice as rock—and add it to this book. One undertakes such a task only if one truly yearns for it. Yet, just before it vanishes—in my lifetime—they will endure. For now, however, I find myself in a fertile state. I write so abundantly that I scarcely have the time to shape it all into a book.

Jhilam Chattaraj

You were alone in Pacung, and you had such singular experiences. You engaged with the locals as well—what did you discover about yourself?

Sudeep Sen

I realised how much more I desire this life, rather than the one confined to work and home. Boundaries, once abstract, have now dissolved—and I find that I can be content. When one’s basic needs are met, language becomes irrelevant. It is more an affirmation than a discovery.

Jhilam Chattaraj

In Pacung, daily life is rooted in ritual. What did you observe?

Sudeep Sen

Their savings are devoted to temple rituals. They live with great modesty, while the rituals themselves are exuberant—highly aesthetic as well. Attention to detail is paramount: the petals of each flower, the evenly divided bamboo strips. They lead deeply sustainable lives.

Jhilam Chattaraj

So, would you wish to return to life in Pacung?

Sudeep Sen

Yes—since I found my solitary place there. But I usually manage to find a quiet corner, even in large cities, once I’ve settled my desk.

Jhilam Chattaraj

Did you feel lonely in Pacung?

Sudeep Sen

Not at all. There were the staff and the neighbours of my friend Philip. My curiosity about life and people kept me company. And then there were the two enormous geckos—or perhaps Komodo dragons—each nearly fifteen feet long. A decade ago, I might have worried about them entering the house, but now I don’t. I accept their presence. I felt entirely at ease.

And then there were the dolphins—a truly joyful sight. My friend remarked that, apart from humans, dolphins are the only creatures known to engage in sex for pleasure. Simply by observing the surface of the water, one could sense the presence of fish. I spent that time attuning myself to the language of nature—time is so fleeting.

Jhilam Chattaraj

As co-chair of APWT, you attended the recent meeting in Chiang Mai, Thailand—was it creatively fulfilling?

Sudeep Sen

Of course—it’s a wonderful opportunity for writers and artists, both emerging and established, to connect and share our work.

Jhilam Chattaraj

Can we expect a poetry collection centred on South East Asia?

Sudeep Sen

Yes, I’m currently working on a collection.

Jhilam Chattaraj

After such a creatively fulfilling time in recent months, what would your parting message be?

Sudeep Sen

As Elizabeth Barret Browning wrote:

A thousand flowers, each seeming one

That learnt by gazing on the sun

To counterfeit his shining;

Within whose leaves the holy dew

That falls from heaven has won anew

A glory, in declining.

May a hundred flowers bloom… may flowers bloom for me… may the fountainhead remain ever fecund.

How to cite: Chattaraj, Jhilam and Sudeep Sen. “I Was Rapt in The Theatre of Skies: A Conversation.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 11 Jun. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/06/011/sudeep-sen.

Jhilam Chattaraj is an academic, critic, and poet. She teaches in the Department of English and Foreign Languages at RBVRR Women’s College, Hyderabad. She is the author of Sudeep Sen: Reading, Writing, Teaching, Noise Cancellation (2021), Corporate Fiction: Popular Culture and the New Writers (2018), and When Lovers Leave and Poetry Stays (2018). Her work has appeared in Michigan Quarterly Review, Mekong Review, Ecocene, New Contrast Magazine, One Art Poetry Journal, Calyx, Ariel, Room, Porridge, Queen Mob’s Teahouse, Colorado Review, World Literature Today, Asian Cha, among others. She received the CTI Excellence Award for ‘Literature and Soft Skills Development’ (2019) from the Council for Transforming India and the Department of Language and Culture, Government of Telangana, India. Her poem “Sari” was nominated for the Nina Riggs Poetry Award (2023).

Sudeep Sen is a leading international poet whose prize-winning works include Postmarked India: New & Selected Poems (HarperCollins), Aria (A.K. Ramanujan Translation Award), Fractals: New & Selected Poems | Translations 1980–2015 (London Magazine Editions), EroText (Penguin), Kaifi Azmi: Poems | Nazms (Bloomsbury), and Anthropocene (Pippa Rann, Rabindranath Tagore Literary Prize). Red and Rock complete The Eco Trilogy. He has edited landmark anthologies such as The HarperCollins Book of English Poetry, Modern English Poetry by Younger Indians (Sahitya Akademi), and Converse: Contemporary English Poetry by Indians (Pippa Rann). Forthcoming titles include Blue Nude: Ekphrasis & New Poems (Jorge Zalamea International Poetry Prize), Rock, and The Whispering Anklets. Sen’s photography—represented by ArtMbassy, Rome/Berlin—is held in both private and public collections. He was awarded the Government of India’s senior fellowship for “outstanding persons in the field of culture/literature.” Notably, Sen is the first Asian to be honoured with the Derek Walcott Lecture and to read at the Nobel Laureate Festival. Visit his website for more information.