📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

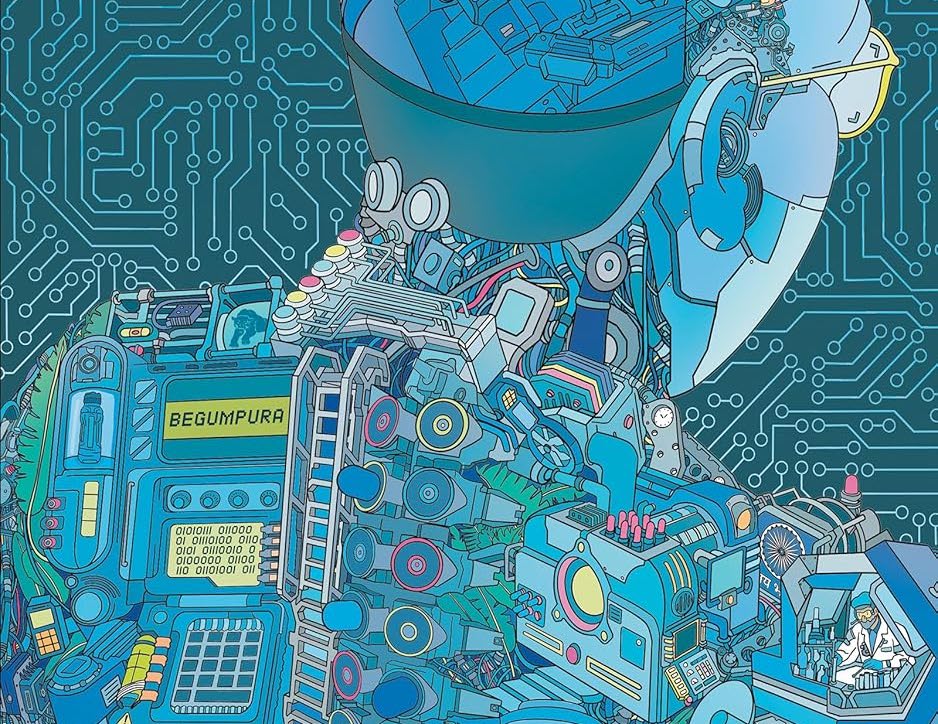

R.T. Samuel, Rakesh K. and Rashmi R.D. (editors), The Blaft Book of Anti-Caste SF, Blaft Publications, 2025. 428 pgs.

It is a curious irony that speculative fiction—so often described as the genre of boundless imagination—has, in the Indian context, remained tethered to the very social orthodoxies it purports to transcend. Within the realm of speculative fiction, a genre that has long professed to defy the constraints of reality, one might reasonably expect a liberation from the oppressive logics that govern our everyday existence. Yet, all too often, this promise is betrayed. The genre, for all its imaginative scope, frequently remains beholden to the ideological prejudices of its creators.

In India in particular, speculative fiction has seldom cast its gaze downwards—into the trenches of caste, the crucibles of marginalisation, the lives of those rendered “unimaginable” by the dominant social order. It remains conspicuously upper-caste. The very idea of speculative fiction—fiction that dares to imagine otherwise—has long been colonised by dominant castes whose visions of the future, ironically, are constrained by their unacknowledged privilege. And yet, if there exists any genre equipped to dream radically different futures, it is surely this one. Speculative fiction, at its finest, operates as a kind of narrative laboratory—a space in which the axioms of our time may be dismantled and reconfigured into radically unfamiliar forms.

The Blaft Book of Anti-Caste SF seeks to offer a corrective. It is a collection of weird, fantastic, and futurist fiction by Dalit, Adivasi, and other marginalised writers. The editor deftly diagnoses the exclusions inherent in mainstream speculative fiction and positions the anthology within what is described as a “bubbling countercultural renaissance”.

The stories themselves are protean and richly layered, drawing upon vernacular sources and rendered into English with verve and sensitivity. The anthology’s scope is striking—from conventional prose narratives to graphic stories, solarpunk vignettes to mytho-futurist fables, horror allegories to satirical parodies of the internet age. The book opens a capacious imaginative space in which the speculative is not a form of escapism but a sedimented terrain—haunted by caste, gender, labour, and belief.

In many ways, reading The Blaft Book of Anti-Caste SF recalled another equally bracing and unsettling anthology: Don’t Want Caste, a collection of Malayalam short stories by Dalit writers, published by Navayana. This is not to suggest a direct comparison between the two volumes.

In a collection as thematically expansive and diverse as The Blaft Book of Anti-Caste SF, it is neither possible nor desirable to anatomise every story within the confines of a single review. Instead, I shall reflect on those narratives that most profoundly unsettled me—one of which is Sumit Kumar’s “Spacewali”. Kumar extrapolates the logic of the present into the vast imaginative canvas of science fiction. In this envisioned future, humanity has succeeded in colonising other planets, rupturing the fabric of space-time, and establishing new imperial outposts beyond Earth. And yet, caste persists—adapted, calcified, and reinscribed within the cosmic order.

At the centre of the narrative is a domestic worker tasked with cleaning up after astronauts in orbit. Two astronauts, embodying the familiar binary of “upper” and “lower” caste men, engage in a desultory debate on reservations. As they argue, the worker silently mops up their waste. The juxtaposition encapsulates the very architecture of caste discourse in elite spaces, where the materiality of oppression is consistently relegated to the background in favour of smug pontification.

Another standout in the anthology is “Meen Matters”. Set in a dystopian Chennai unravelled by a zombie outbreak, the narrative affirms that the undead, too, may be marshalled as metaphor. The elite have retreated into fortified villas. In this zombified metropolis, territorial control has passed to street gangs—among them, the unforgettable all-woman collective known as The Birthday Gurlz. Devadasan’s prose—or more precisely, his narrative texture—exhibits a remarkable attunement to the rhythms and registers of Tamil cultural life.

Shivani Kshirsagar’s “The House Is Never Clean” operates at the uncanny threshold between the domestic and the digital, refracting horror fiction through the affective sediments of caste and the banal violences of upper-middle-class cleanliness. At first glance, it may appear to be a familiar tale of internet-age eeriness; yet to read it solely as psychological horror would be to overlook the deeper architectures of social contagion and embodied caste trauma that the story so astutely reveals. The family inhabiting the house is rendered with a surreal opacity—alien, almost automaton-like—emotionally vacuous and hyper-disciplined. This estrangement of the employer class is telling: it gestures towards caste not as a system perpetuated by monstrous individuals, but as a structural coldness, a refusal of relationality, a compulsive insistence on bodily separation and “purity”.

Gogu Shyamala’s “The Phantom Ladder” and Snehashish Das’s “Death of a Giant in a Godless Country” offer more overt political allegory. Both stories interrogate the theological and ideological contortions by which caste is rationalised, holding up a distorted mirror to some of Indian society’s most deep-seated hypocrisies. In “Hallucination Stream”, Sahej Rahal orchestrates a cosmic collage—drawing on ancient South Asian cosmology, Hindu mythology, media theory, and late capitalism—to expose the caste system not merely as a social pathology but as a metaphysical nightmare.

Notably, the anthology resists any impulse to homogenise its voices. Each story constitutes a sovereign universe, stylistically and thematically distinct. Some lull the reader with whimsy before descending into dystopian depths; others pare the narrative down to an almost mythic minimalism. Several turn to speculative horror and mythopoeia to excavate the subterranean logics of caste. The collection is remarkable precisely because it eschews both the elite cosmopolitanism of mainstream science fiction and the tragic realism into which Dalit literature is so often consigned. Instead, it forges a hybrid literary mode—wildly imaginative, often humorous, at times bleak, always incisive—that remains deeply rooted in the real, even as it conjures other worlds into being.

How to cite: Singh, Ananya. “The Fierce Imagination of Anti-Caste Speculative Fiction.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 11 Jun. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/06/11/anti-caste.

Ananya Singh is a writer. Her work has been published in FirstPost, Deccan Herald, Madras Courier, and elsewhere. She can be contacted via ananyadhiraj7@gmail.com and @anannnya_s on Instagram and X. [Read all contributions by Ananya Singh.]