Plato, in The Symposium, conceives of Eros as a love for the ideals of beauty and goodness—symbolising spiritual communion within and between souls. Later, Sigmund Freud introduced Eros into ontology: “Existence is essentially a pursuit of love, which becomes the goal of human survival. The erotic impulse to integrate living beings into a larger, more stable unit constitutes the instinctual root of civilisation.” Although Freud emphasised the ontological significance of Eros, it was Herbert Marcuse who fully elucidated the metaphysical dimensions of Freud’s thought. For Marcuse, Eros attains supreme status as a trinity of life, freedom, and beauty—serving as both the highest ideal and the model of civilisation. Precisely because of the deprivation of human Eros, genuine pleasure becomes unattainable in art; people are left only to amuse themselves like Pavlov’s dogs, passively responding to the dictates of conditioned reflexes and hypnosis.

The films of Hong Sang-soo persistently evoke the pursuit of Eros as a life instinct. They interrogate moral yet hypocritical ideals, while unearthing the awkwardness and abrasiveness of daily existence. His dual plotlines and circular narrative structures serve to complete the self-repetition of individual emotion—and these are, inevitably, bound to his goddess of freedom and love: Kim Min-hee.

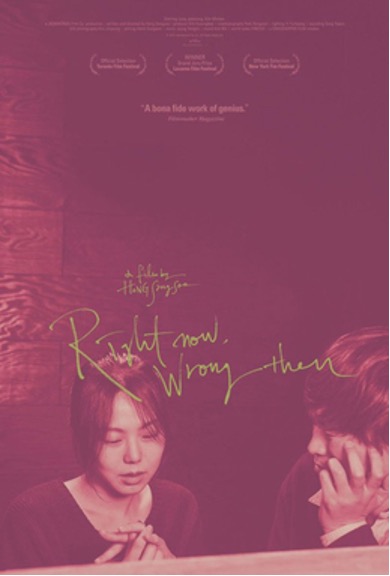

With Right Then, Wrong Now (2015), Hong inaugurated a defining chapter in his cinematic oeuvre—the “Kim Min-hee era.” In interviews, he has unreservedly referred to her as his “muse.” Part of the pleasure in watching Hong’s films lies in tracing narrative and visual clues, and connecting them with public speculation about their personal relationship. The real-life Kim Min-hee and her on-screen persona gradually merge, giving vivid form to the figure of a goddess of life and freedom—no longer a vague presence, but a luminous, incarnate force.

Right Now, Wrong Then (2015)

Hong Sang-soo’s films undeniably underwent a qualitative shift in creative direction following the advent of the “Kim Min-hee era.” Foremost among these changes is a shift in narrative perspective. In his earlier works, the protagonist is typically a “kitsch” and melodramatic male figure, with the narrative unfolding predominantly from his point of view and gradually extending to encompass other characters—focusing primarily on the emotional dynamics and professional preoccupations of these male roles.

For instance, in The Day a Pig Fell into the Well (1996), the story centres on a male writer entangled in a love triangle—or quadrangle—defined by unrequited desire. In The Power of Kangwon Province (2000), the male protagonist, facing a mid-life crisis, sets off on a journey with two women he meets during a trip arranged by a friend, propelling the narrative forward. Even in Right Then, Wrong Now, the film is structured around two nearly identical segments, both centred on the male lead, played by Jeong Jae-yeong, with Kim Min-hee’s female character functioning largely as a complementary presence.

The Day a Pig Fell into the Well (1996), screenshot

The Power of Kangwon Province (2000), screenshot

However, after Right Then, Wrong Now, a noticeable shift began to take place. Perhaps owing to his profound admiration for Kim Min-hee, Hong Sang-soo’s films gradually moved from a male-centred to a more female-centric perspective. In On the Beach at Night Alone (2017), a woman flees Seoul under the emotional strain of an extramarital affair with a married man. She visits friends and finds solace by the sea, ultimately attaining a sense of tranquillity as expansive as the ocean itself. Grass (2018) opens from the perspective of a female writer seated in a café, quietly observing those around her to spark inspiration while reimagining the narratives of strangers. Whether the other characters are real or figments of her imagination remains deliberately ambiguous.

In Claire’s Camera (2017) and subsequent works, Hong consciously explores themes of workplace injustice faced by women, evoking feelings of indignation, awakening, discomfort, and quiet bitterness. In contrast, male figures in these films are deliberately belittled, marginalised, or rendered as stereotypes—sleazy, arrogant, evasive. Hong’s male leads exhibit a striking uniformity: directors, writers, professors—figures with ostensibly prestigious social status but emotionally stunted and unfulfilled romantic lives. Much of the awkwardness and tension in these films arises from the men’s frustrations and their futile efforts to conceal them, laying bare flaws such as cunning, cowardice, hypocrisy, and vanity.

This critical portrayal of male characters can be traced back to The Day a Pig Fell into the Well, where the protagonist—a third-rate writer—insists on attending a publishing party uninvited, vents his resentment on a female server who accidentally spills soup on him, and ends up in a humiliating altercation involving a broken beer bottle. The episode foreshadows the restless, hypocritical male archetype that recurs in Hong’s later work.

This tendency reaches its apotheosis in The Woman Who Ran (2020), where male characters are scarcely visible: a neighbour complaining about stray cats, a young poet harassing Kim Min-hee’s friend, and her ex-boyfriend, now married to that same friend. In these fleeting appearances, men are often shown with their backs turned to the camera. These awkward, diminished male figures serve as a foil to the independence of female characters like Kim, who reject kitsch and renounce emotional dependence on men. The gradual disappearance of male roles thus symbolises a broader rejection of kitsch itself.

In On the Beach at Night Alone, Kim’s character undergoes a transformation—from emotional fragility to a conscious awakening—ultimately embracing self-reliance over dependency. Through layered conversations—ranging from life abroad to foreign men and, eventually, to questions of survival—she sheds external attachments and returns to a sense of authentic selfhood.

On the Beach at Night Alone (2017), screenshots

Grass (2018), screenshot

The Woman Who Ran (2020), screenshot

While the belittlement of male characters serves to highlight female autonomy, one may ask why Hong insists on portraying men as so excessively petty, despicable, and at times even detestable in his collaborations with Kim Min-hee. The answer lies in Hong’s acts of self-deconstruction and devotion. Beyond the films themselves, Hong and Kim’s controversial relationship was a dominant subject in the Korean media. Tracing the timeline of their collaborations reveals a series of intimate parallels: Right Then, Wrong Now features a married man pursuing Kim; On the Beach at Night Alone mirrors an actress fleeing public condemnation for an affair with a director; Claire’s Camera and Grass reflect a period of emotional stability; The House by the Creek (2017) transcends romantic love to explore spiritual connection; and The Woman Who Ran presents Kim with a short haircut and alludes to a five-year “glued” marriage—precisely the length of their artistic partnership from Right Then, Wrong Now to The Woman Who Ran. These parallels suggest that Hong’s films function as personal reflections of his evolving relationship with Kim.

Moreover, the recurring contempt for male characters in his films constitutes an act of self-condemnation. The selfishness, hypocrisy, and awkwardness portrayed are not merely generalised critiques but confessions—Hong’s own flaws laid bare. In exposing these vulnerabilities with such candour, he gestures toward the deeper truth of Eros: that while “love” may resist clear definition, its precondition is the courage to transcend the ego and truly recognise the other. Two individuals encased in their own self-constructed cocoons cannot genuinely love. The desire for a “soulmate” who mirrors one’s every preference is not love but narcissism—a dangerous illusion that ensnares one in a self-reflective abyss.

Hong’s films reject this narcissism. Instead, they depict powerlessness as a constructive condition for love—an admission of vulnerability before the other. This is not a passive surrender, but an active ethical stance. In Right Then, Wrong Now, the male protagonist’s initial evasiveness fails, whereas his honest confession in the film’s repeated scenario succeeds. By embracing his powerlessness, he creates space for Eros to emerge—recognising that such powerlessness is the price of true devotion, one that allows the other to exist in their fullness and Eros to manifest.

“I only stop trying to mould the other into my ideal self when I admit powerlessness”—this vulnerability, far from weakness, is a profound form of respect. Only through such surrender can the other truly appear, and Eros be realised. The awkward, self-important male figures in Hong’s films serve as a form of self-critique—his flaws refracted through Kim’s quiet rejection, and ultimately, a testament to the depth of his love for her. Love, in this sense, draws the subject out of their ego and into the world of the other, inspiring a voluntary self-forgetfulness. To fall in love is to be made both weaker and stronger—a paradox that narcissism cannot accommodate, a gift granted only by the other, or by love itself.

The world becomes “ours”, not “mine” or “yours”—a new reality forged through mutual sacrifice. While radical self-denial in love may seem a daring experiment, embracing the other without boundaries reveals a deeper truth: that loyalty, at its most intense, is a struggle against the solitude and oblivion of the individual self.

On the one hand, Hong critiques his ego through relentless acts of self-flagellation in order to nurture Eros; on the other, he endlessly romanticises the other through Kim. His films lavish praise on her appearance, temperament, and intellect—characters such as a little girl, a taxi driver, and even Isabelle Huppert all serve as vessels for Hong’s voice. Kim becomes an a priori symbol of beauty, transcending the films themselves to embody the “form” of love and beauty within Hong’s cinematic universe.

In contrast to Shunji Iwai—who professes to explore the notion of pure love—Hong’s conception is far more radical, rooted in an experiential dialectic between self and other. His films eschew dramatic plotlines, often revolving around simple visits and quiet conversations, yet it is precisely within this banality that Eros awakens—unexpected and luminous. The ambiguity and variation embedded in his dual or circular structures evoke the “immunological stimulus” of Kim as muse: he anatomises himself to the point of exposed humility, rejects homogenised language while adhering to a restrained, consistent style, and becomes obsessed with minute variations across seemingly similar narratives.

In many of his conclusions, Kim is subtly withdrawn from the diegesis—shielded from becoming a commodified icon within a consumerist culture. His goddess of love remains veiled, a contemplative figure observing her own life, as if seated among the audience. The anguish, melancholy, awkwardness, and gentle descent that permeate Hong’s films function as a quiet critique. Amid the interplay of truth and fiction, lovers’ confessions offer an anchor—granting a flicker of colour in an otherwise monochrome world. It is a “qualification for love” known only to them, as whispered in On the Beach at Night Alone.

How to cite: Xu, Hanyin. “The Manifestation of Eros: On the Construction of the Eros Image in Hong Sang-soo’s Films.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 31 May 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/05/31/eros.

Hanyin Xu (Yazmin Xu) (Malaysia), born in Taizhou, Zhejiang in 1998, is a PhD student in Art History and Theory at the Institute of Malay Studies, University of Malaya. Her research centres on contemporary public art and marginalised communities in Southeast Asia, with particular emphasis on aesthetic and critical practices within postcolonial contexts. Through her work, she seeks to interlace artistic expression with the emotional resonances of overlooked voices—striving to unveil the whispered histories embedded in public spaces. She conceives of art as a conduit between memory and resilience, persistently exploring its capacity to cultivate an emotional community that transcends boundaries, inviting audiences to perceive the intricate tapestry of marginalised experience through a lens of empathy and critical reflection. Personal Website: yazminxu.com | Instagram: @yyyazminxu