📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

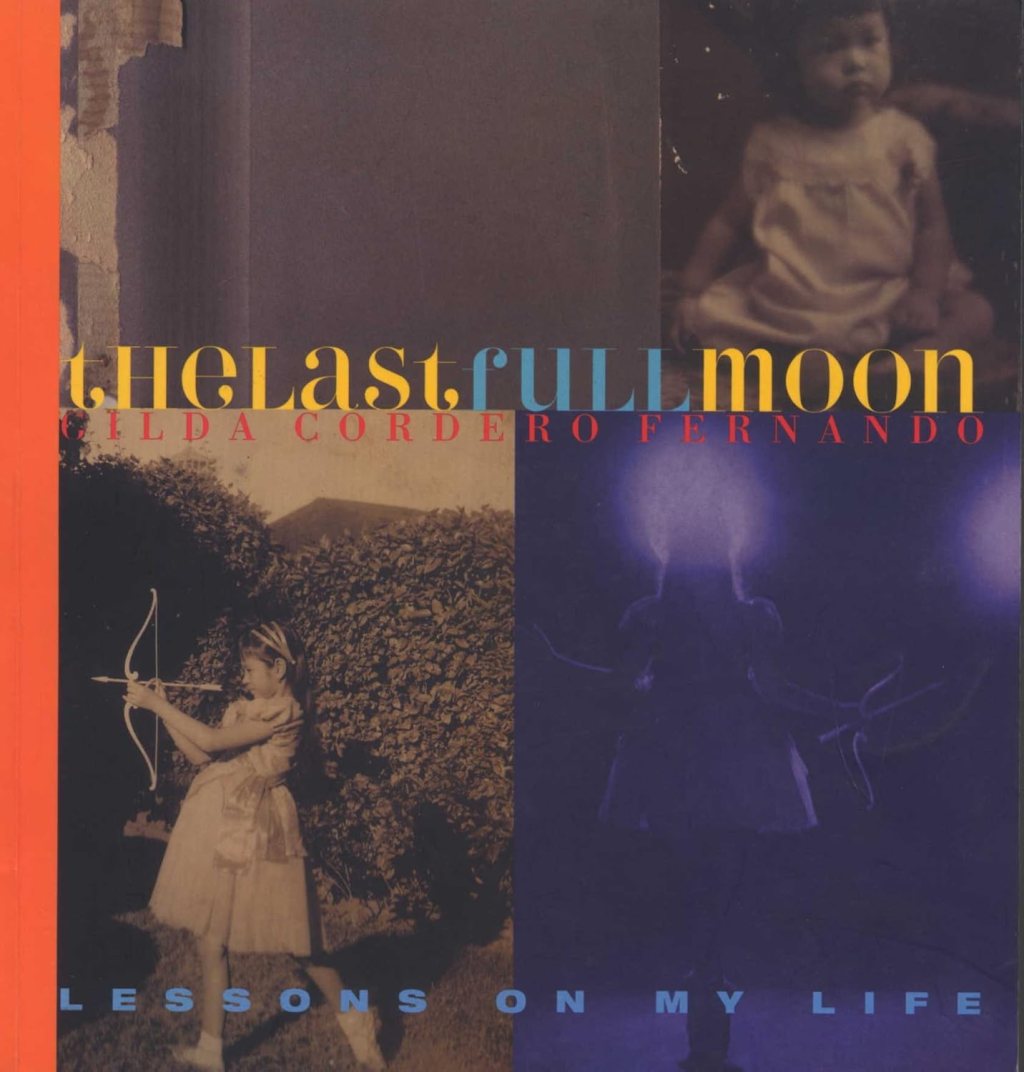

Gilda Cordero-Fernando, The Last Full Moon: Lessons on My Life, University of the Philippines Press and GCF Books, 2005. 250 pgs.

“I don’t want to be boring ever.”

—Chappell Roan, queer pop sensation

Writer and cultural icon Gilda Cordero-Fernando (GCF), like most of the greats, was well ahead of her time. She was an it-girl then—and had she been active today, in the age of algorithms on BookTok and Bookstagram, she would undoubtedly still be one now.

“She is a national cultural visionary… an outstanding voice in the expression of the evolving Filipino world view,” says Mariel Francisco, GCF’s close friend and fellow writer (qtd. in Caruncho and De Vera). Upon reading GCF’s magnum opus, The Last Full Moon: Lessons on My Life—a memoir—I could not agree more. I believe her quirky and compelling voice will continue to resonate with generations of young Filipinas (and Filipinos more broadly) in their enduring quest for empowered female figures to admire.

GCF had been serving—and slaying—since the 1930s. Tragically, she passed away at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, aged 90. I, too, mourn her—even as a stranger who only recently discovered her work. There is something profoundly uncanny about coming to “know” someone only after their passing. As someone who predominantly consumes works by living writers and artists, it felt surreal that this funny, brilliant, and now-departed woman could seem so palpably alive in her prose. Through her words, she made me snort, laugh, gasp, and empathise—even from beyond the grave. I was heartbroken to realise I would never meet her in the flesh.

She published The Last Full Moon in 2005, chronicling her journey from childhood to her later years. Her many selves form the heart of this memoir. We encounter GCF as daughter, wife, mother, grandmother, friend, writer, publisher, and cultural worker, among others.

Each essay reveals a distinct self, one that resists the rigid constraints of a once-overly conservative society determined to entrap women within the antiquated Maria Clara archetype. GCF lived through an era that often cast women as either eternal virgins or dutiful housewives. And though she herself was once labelled a “housewife” in official documents, she refused to be confined by the limitations such a role imposed. All her life, she resisted those expectations—and triumphed. She became infinitely more.

GCF found freedom in her art. She portrays her many invented selves as “active agents” (Zinsser 45) who refused to be limited or constrained by circumstance. She quite literally—and figuratively—carved out spaces for herself. She pursued work not out of necessity, but out of a relentless drive to create and contribute. Ever dynamic, she was constantly in motion, moving towards the next venture that captured her curiosity and passion.

This desire to create continually propelled her towards a multitude of achievements—including the writing of this memoir, a compiled collection of personal essays that constitutes a hybrid form in itself.

What I admire most about this memoir is the authenticity of GCF’s invented selves. She presents herself as a flawed, multifaceted woman simply trying to live. Although she faced considerable criticism throughout her career—for being too much, too raw, too confessional—it is precisely this very “too-muchness” that endears her to me as a reader. Our generation (not that I claim to speak for it) would have embraced this memoir wholeheartedly. We would have been her ideal audience, for nothing—and I mean nothing—is too confessional for us. With the right exposure, thoughtful marketing, and widespread reprinting and distribution, this tell-all would undoubtedly be a runaway success.

GCF deftly sidesteps the ethical dilemma inherent in the genre and in confessional storytelling by virtue of having outlived almost everyone she mentions. She pays tribute to her late parents, grandparents, friends, son, and others, while remaining truthful about her lived experiences. A particularly poignant example is her depiction of the fraught relationship with her mother. Writing about her in this way enables GCF to articulate emotions she had previously been unable to express. It grants her—and those implicated—the “gift” of emotional truth (Lopate 73).

Even more fascinating is her promise to release an “uncensored” posthumous version of the memoir thirty years after its initial publication (see p. 87). This foresight affords her greater freedom to divulge difficult truths and express herself with fewer constraints—a wise and calculated decision.

The essays are compiled and loosely arranged according to the stages of life. Though not explicitly divided into sections, the memoir clearly follows a structure that progresses from childhood through adolescence to adulthood. Despite its chronological foundation, each essay is crafted in such a way that the memoir may be read non-sequentially. GCF occasionally repeats details previously mentioned in earlier essays, mindful that readers may not have encountered those prior pieces or retained all particulars. This approach allows each essay to stand alone while still contributing to the larger narrative whole.

It echoes a key principle from my creative nonfiction class: the essayist must never assume the reader has encountered any of their earlier work. And it works. The memoir does not overwhelm the reader with the burden of constant recollection. One may return to a single essay without feeling compelled to reread all that came before it.

Although this hybrid compilation of a life may no longer be considered “new” in today’s literary landscape, I believe GCF’s memoir was remarkably innovative for its time—and remains strikingly relevant even now. It was ahead of the curve, a trendsetter in its own right, at a time when locally, the prevailing norm was novel-length autobiographies, largely authored by men. The only other Filipina-written memoir or collection of personal essays from the early 2000s I could identify was Kerima Polotan-Tuvera’s The True and the Plain: A Collection of Personal Essays, which was published in the same year GCF released her memoir.

Beyond being a trailblazer and a foundational text in the Philippine creative nonfiction genre, GCF’s memoir endures because it speaks to timeless, universal experiences of girlhood—experiences that continue to resonate with modern Filipinas like myself, irrespective of social class.

GCF’s heart and humour radiate from every page. Her voice is unforgettable, her stories indelible. To borrow the vernacular of Gen Z: she completely ate down—and grandmothered.

Bibliography

▚ Browning, Maddie. “Pop Star Chappell Roan: ‘I Don’t Want to Be Boring Ever.’”

▚ BostonGlobe.com, 27 Mar. 2024, www.bostonglobe.com/2024/03/27/arts/chappell-roan.

▚ Caruncho, Eric S. and De Vera, Ruel S. “Writer, Artist Gilda Cordero-Fernando; 90.”

▚ Lifestyle.INQ, 28 Aug. 2020, lifestyle.inquirer.net/369496/writer-artist-gilda-cordero-fernando-90.

▚ Fernando, Gilda Cordero. The Last Full Moon: Lessons on My Life. The University of the Philippines Press, GCF Books, 2005.

▚ Lopate, Phillip. “On the Ethics of Writing About Others.” Creative Nonfiction 40 (Winter 2011): 72-73. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44364650.

▚ “The True and the Plain: A Collection of Personal Essays.” Goodreads, www.goodreads.com/book/show/1827413.The_True_and_the_Plain.

▚ Zinsser, Judith P. “Feminist Biography: A Contradiction in Terms?” The Eighteenth Century 40.1 (2010): 43-50.

How to cite: Tanguin, Janelle. “Grandmothered! A Filipina Gen Z’s Critique of Gilda Cordero-Fernando’s The Last Full Moon.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 27 May 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/05/27/last-full-moon.

Janelle Tanguin is currently pursuing an MFA in Creative Writing at De La Salle University. Like many of her Generation Z contemporaries, she inhabits the digital realm almost perpetually. A selection of her personal essays and poems can be found online.