📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

Anand Patwardhan, Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam (The World is Family), 2023. 96 min.

“யாதும் ஊரே! யாவரும் கேளிர்!” (“Every place is our homeland, everyone is our kin”)—these words from the Tamil Sangam poet Kaniyan Poongundranar carry a striking urgency in our present moment. Two millennia ago, this vision of borderless humanity found eloquent expression in his poetry, later reverberating through various Indian philosophical traditions. Today, however, we are confronted with the paradoxical appropriation of such inclusive philosophies by forces of exclusion. When Hindutva ideologues invoke Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam (“The world is family”), they reframe a radical vision of universal kinship into a slogan for promoting a homogeneous, exclusionary conception of India.

Yet this appropriation has not gone unchallenged. For over five decades, filmmaker Anand Patwardhan has chronicled India’s ongoing struggles for inclusivity, his camera bearing persistent witness to resistance movements. His documentary film The World is Family marks a distinctive inward turn, using family history as a lens through which to illuminate broader political truths. Through intimate portraits of his own family’s involvement in the Indian independence movement, Patwardhan reclaims an alternative vision of India—one rooted in pluralism and genuine fraternity.

At the heart of the film are Patwardhan’s parents, who emerge as its most compelling storytellers. There is Nirmala, his “funny mom,” whose irrepressible spirit lights up every frame she appears in. A graduate of Shantiniketan, she embodies the artistic sensibility of her alma mater—whether moulding clay with practised hands or delivering wry, sharp-witted observations that catch the viewer delightfully off guard. Her irreverence feels like a quiet form of rebellion—a testament to the understated ways individuals preserve their independence of thought. Then there is Balu, his father, whose gentle presence imbues each scene with a quiet, abiding warmth. Together, they are more than narrators: they become intimate guides through the corridors of memory, rendering history not as distant abstraction but as something lived, tangible—as immediate as a conversation around a family dining table.

Through the rediscovered diary of his uncle, Purushottam Rau Patwardhan, we encounter a mind grappling with Trotsky’s radical vision in dialogue with Gandhian principles of non-violence. Each entry reveals the independence struggle not as a monolithic movement but as a rich tapestry of ideological diversity. His writings capture the intellectual labour of one man striving to reconcile revolutionary socialism with satyagraha, forging a singular and deeply personal conception of freedom.

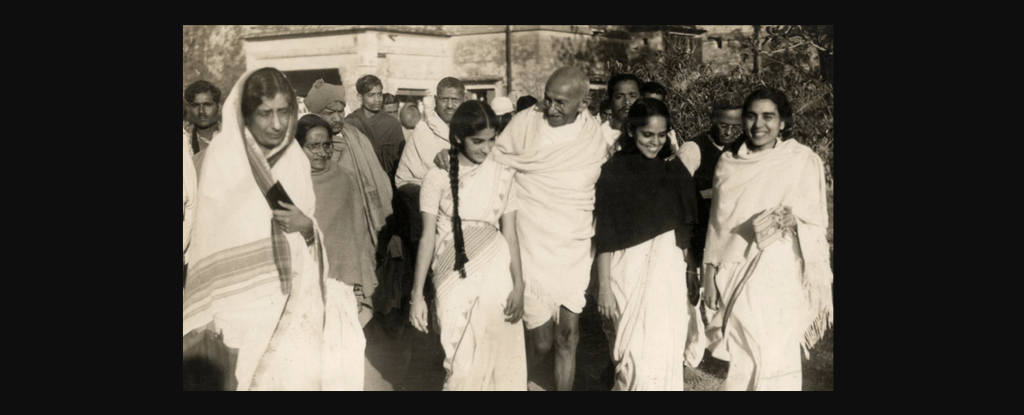

What is truly remarkable is the fluidity of their recollections. One moment, Nirmala is laughing about her love for pottery; the next, she is recounting the tension in Calcutta during the riots. Balu may begin with a gentle family anecdote that unexpectedly unfolds into a vivid account of the Salt March. They lived through independence, partition, and Gandhi’s assassination—yet in their telling, these are not the grand historical events we encounter in textbooks. Instead, we are offered history as it was lived: incomplete, tangled, deeply personal.

It is, however, in its treatment of contemporary communal tensions that the film strikes its most powerful notes. Patwardhan’s journey to Pakistan—where his ancestral home now serves as a hospital—quietly reveals the constructed nature of our divisions. Even more affecting are his conversations with children about recent riots. When a young Hindu boy slowly comes to recognise his community’s role in instigating violence, we witness the possibility of unlearning inherited prejudice. And when a young girl asks, “Why do people keep fighting if it causes death?”, the camera cuts to a silent image of a Buddha statue. The stillness that follows says everything about our failure to justify hatred in the presence of innocent clarity.

As the documentary shifts between archival footage and present-day scenes, it mirrors the workings of memory itself—not linear but cyclical, weaving together past and present in unexpected ways. Small moments—family meals, casual conversations, shared laughter—accumulate into something profound. They reveal how history is embedded in everyday experience and how personal memory can question, complicate, and sometimes subvert official narratives. In a time when particular political forces weaponise reductive versions of history, the film becomes essential viewing. Patwardhan reminds us that historical truth lies not in monolithic accounts but in the multitude of voices that speak both to and against them. In an age of hardening boundaries, the film offers an alternative vision—one in which shared humanity outweighs the lines we draw between ourselves.

The documentary teaches us that the task is not simply to challenge the adage that history is written by the victors, nor merely to preserve alternative accounts. Rather, it insists that every fragment of memory, every whispered story, every thread of oral tradition holds significance precisely because it exists in the interstices between official histories. Through Patwardhan’s lens, we come to understand how personal and familial memories serve as counter-narratives—vital testaments to experiences overlooked or deliberately excluded. This is not a call to smooth over the fractures in our history, but to recognise them as crucial spaces—where marginalised voices persist, and where forgotten truths await their due remembrance.

How to cite: Annamalai, Kathiravan. “Between Memory and History: Anand Patwardhan’s Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 26 May 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/05/26/world-family.

Kathiravan Annamalai is a Research Scholar in the Department of English at Pondicherry University. His doctoral research explores comparative perspectives in the dramatic literature of the Harlem Renaissance and the Dravidian Movement. His broader research interests encompass Indian Literature in English, Subaltern Studies, Drama, and Translation Studies. He has presented papers at various national conferences and has published research articles in peer-reviewed academic journals. [All contributions by Kathiravan Annamalai.]