📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

Uketsu (author), Jim Rion (translator), Strange Pictures, HarperVia, 2025. 240 pgs.

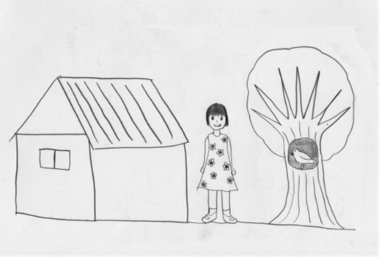

In the Prologue, we are told: “All right, everyone, now I’m going to show you a picture.” The picture is drawn by an eleven-year-old girl who has been arrested for the murder of her mother—

The psychologist tells us that a drawing produced by a patient in response to a prompt can be used to analyse the patient’s mental state—

Like they say, “painting is a mirror of the soul,” and a drawing can often offer valuable insight into the mind of its artist. In particular, drawings of houses, trees and people tend to be remarkably revealing.

The psychologist concludes that the eleven-year-old girl had “a strong chance at rehabilitation”—and indeed she did, as she was now living “happily as a mother”.

We then move on to three entirely distinct narratives, seemingly unconnected to the drawing and psychoanalysis of the Prologue. Yet, as we well know, prologues often serve as a form of foreshadowing, carrying with them a key connection or underlying significance. The final chapter, entitled “The Bird, Safe in the Tree”, suggests a tidy resolution to the various disparate threads woven throughout the book.

The first story concerns a pair of students who discover a peculiar blog, with years of entries missing, which ends abruptly following the death of the blogger’s pregnant wife during childbirth. The second centres on a single mother’s attempts to protect her son, while the third recounts the experiences of an ambitious young journalist who uncovers the story of a brutal, unsolved murder of an art teacher on a remote mountain. Though each narrative appears separate, all are laced with numerous clues and ultimately converge in ways the reader must uncover.

These connections are hinted at through drawings presented at the beginning of each chapter: an elderly mother kneeling, a mother and child before an apartment building, and a mountainous landscape. The novel also incorporates maps, floor plans, and blog screenshots. Might these images hold the key to the mystery? Each chapter’s illustrations conceal secrets that are both specific to their respective narratives and integral to the overarching story, subtly introduced in the Prologue. Moreover, each chapter engages with the drawings in a different manner—variously obscuring and revealing the truths they contain.

The psychologist in the Prologue remarks that “children don’t draw the thing that they see with their eyes, they draw the idea in their minds”—offering psychological insight into their mental state—while “adults can draw what they see, the real thing, in their pictures”. To unravel the mysteries within these stories and understand how they interconnect, we must think imaginatively and laterally, like a child, when interpreting the drawings and the various scattered clues. I did not find it particularly easy to piece everything together, though many readers of the novel appear to have succeeded. Reading more slowly may well be the key.

I am wholly in favour of readers being challenged by stylistically distinctive novels, and of writers who seek to push boundaries by incorporating diverse genres and non-textual material into their work, thereby expanding the possibilities of the literary form.

The book also offers a compelling glimpse into the personal tensions embedded in Japanese social structures and culture—particularly the themes of mystery, social alienation, and the economic struggles faced by individuals. These include single mothers and figures such as the aspiring reporter, whose life has been shaped by the economic downturn and scarcity of opportunity that defined the 1990s, often referred to as the “lost generation”. This is a recurring theme in contemporary Japanese literature.

How to cite: Eagleton, Jennifer. “The Reader as Detective: Uketsu’s Strange Pictures.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 21 May 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/05/21/strange-pictures.

Jennifer Eagleton, a Hong Kong resident since October 1997, is a close observer of Hong Kong society and politics. Jennifer has written for Hong Kong Free Press, Mekong Review, and Education about Asia. Her first book is Discursive Change in Hong Kong (Rowman & Littlefield, 2022) and she is currently writing another book on Hong Kong political discourse for Palgrave MacMillan. Her poetry has appeared in Voice & Verse Poetry Magazine, People, Pandemic & ####### (Verve Poetry Press, 2020), and Making Space: A Collection of Writing and Art (Cart Noodles Press, 2023). A past president of the Hong Kong Women in Publishing Society, Jennifer teaches and researches part-time at a number of universities in Hong Kong. [All contributions by Jennifer Eagleton.]