📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

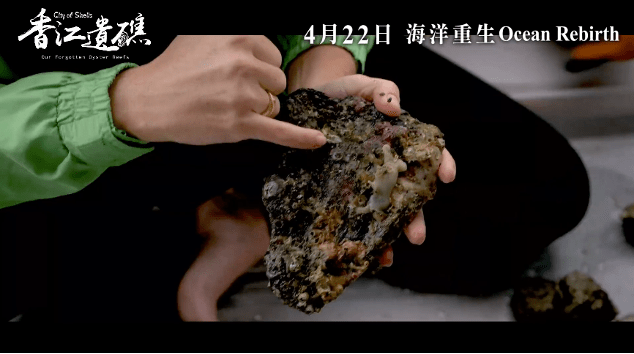

Mike Sakas (director), City of Shells: Our Forgotten Oyster Reefs, 2025. 66 min.

As Robin Wall Kimmerer reminds us, we cannot restore our relationships with nature without also engaging in “re-story-ation.” Her insight resonates with the wisdom of Donna Haraway and Deborah Bird Rose, who insist that storytelling is vital for cultivating response-ability—the capacity to respond and to assume responsibility.

City of Shells is an evocative attempt to re-story Hong Kong’s oysters—and Hong Kong itself. The film opens with a passage from the Record of Lingnan, dating back to the late ninth century: “The Lo Ting sea Barbarians harvest oysters with axes, burn the shells in raging fire, forcing them open.” Lo Ting, a half-man, half-fish figure, stands as one of the most prominent mythological ancestors of Hong Kong’s people, embodying the city’s historic reliance on the ocean for sustenance.

Anchored by the Oyster Reef Restoration Project by The Nature Conservancy, the documentary interlaces narratives concerning the value of oysters and the rationale behind the environmental initiative. It charts the significance of oysters beyond the dinner plate, tracing their longstanding contribution to the city’s socio-economic development. Their shells, for instance, once fed the flames of eleven lime kilns bustling on Peng Chau in the nineteenth century. This versatility may have been a blessing for humans, but a curse for the molluscs—and for the marine ecosystems left in their wake.

The film delves as much into history as into the present. Oysters, we learn, are masterful environmental engineers. A reef merely seven square metres in size can filter an Olympic-sized swimming pool’s worth of water in a single day. The substances consumed are either incorporated into their shells or deposited upon the seabed. The reef also serves as a sanctuary, nurturing biodiversity by providing food and shelter for a host of marine life, including crabs and small fish. These quiet labours—together with their historical contributions—often go unnoticed or are forgotten, yet the film invites us to re-attend and to re-member. This invitation emerges amid an immense irresponse-ability towards the oysters.

Globally, we have lost between 80 and 90 per cent of oyster reefs. Hong Kong’s waters are no exception, scarred as they are by dredging, reclamation and a regulatory regime that fails to recognise the value of oyster habitats. One particularly frustrating story concerns the environmental impact assessment system—a mandatory procedure in Hong Kong intended to evaluate and mitigate the ecological consequences of construction projects—which scarcely acknowledges oyster ecosystems and permits their obliteration.

As the government renders oysters invisible, a moment that lingers with me in the film is when Marine Thomas, Associate Director of Conservation at The Nature Conservancy, draws a distinction between rock and oyster:

When you are not used to observe oyster, they could just look like rocks. But the trick is, when you arrive on the scene, you kind of see them filtering. There is a little bit of movement.

This moment does not tell us why we should respond to oysters; rather, it models how to respond—with hard work, attentiveness, curiosity, care, concern, practice and patience, or, in the words of Deborah Bird Rose and Thom van Dooren, “a curious attentiveness that exceeds the given moment so that we might better understand the other in order to make an appropriate response.”

Cultivating such attentiveness might begin with storytelling, but it will ultimately demand a shift away from the dominant anthropocentric and economic logics that obscure our ability to respond. City of Shells re-stories not only oysters but Hong Kong itself. The film stresses that although the city occupies a mere 0.03% of China’s marine area, it is home to 26% of the country’s recorded marine species.

This narrative counters the hegemonic discourse that flattens Hong Kong into the clichéd image of a financial hub, where all energy is channelled into the economic realm. But what if we understood the city otherwise? What if Hongkongers recognised the ecological wealth that pulses through their waters, trees, parks, roads, skies and beyond? At the time of writing, the Northern Metropolis Project has been approved—threatening to destroy 89 hectares of wetland and the habitat of 205 bird species. To name but one other example among many, a reclamation project now looms over Lung Kwu Tan, putting Chinese white dolphins and countless other marine life at further risk.

Response-ability is not only about response but about responsibility. Van Dooren and Rose caution that responsibility is not a fixed, static endpoint but an ongoing, shifting practice, as “there is no singular ‘responsible’ course of action; there is only the constantly shifting capacity to respond to another.” Responsibility dissolves when it becomes a box to tick—a duty declared done.

And here is where the documentary leaves me wanting more. While it compellingly highlights the Oyster Reef Restoration Project and the value of oysters, it emphasises mitigation efforts without sufficiently confronting the limits of conservation as such. A case in point involves the restoration of oyster reefs around the seawall of the new airport’s third runway—built on reclaimed land—a project that has itself devastated marine life in the area from the outset.

Mitigation is necessary—and yes, it is. But sceptics have long argued that mitigation measures can paradoxically legitimise ecologically disastrous acts and hinder response-ability. For instance, recycling has helped to normalise single-use plastics. In Hong Kong, compensatory mitigation measures have been used to justify various reclamation projects. One sobering example is the marine park designed to protect Chinese white dolphins, whose population has plummeted from 188 in 2003 to just 34 in 2023. The film misses the chance to explore this tension and, in doing so, sidesteps an opportunity to attune audiences to the limits of short-term ecological repair.

Nonetheless, City of Shells is an important and compelling re-story-ation of Hong Kong’s oysters. Watching the film allows us to re-member oysters by seeing their diverse roles and complex entanglement with humans, while at the same time re-imagining Hong Kong as more than a financial city—as a dazzling node of biodiversity that demands greater response-ability.

How to cite: Pit, Hok Yau Tim. “Re-story-ation of the Hong Kong Oyster: City of Shells.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 26 Apr. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/04/26/shells.

Tim Pit Hok Yau is a PhD candidate in Asian Studies at the University of British Columbia and serves as the Research Lead for the Hong Kong Animal Law and Protection Organisation. His research interests encompass non-human animal history and welfare, alongside topics within the Environmental Humanities, including waste studies and the climate crisis. His commentaries and academic work have been featured in a range of media outlets and scholarly journals, including Hong Kong Free Press, Ming Pao, Hong Kong Studies, and Inter-Asia Cultural Studies. [All contributions by Tim Pit Hok Yau.]