📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

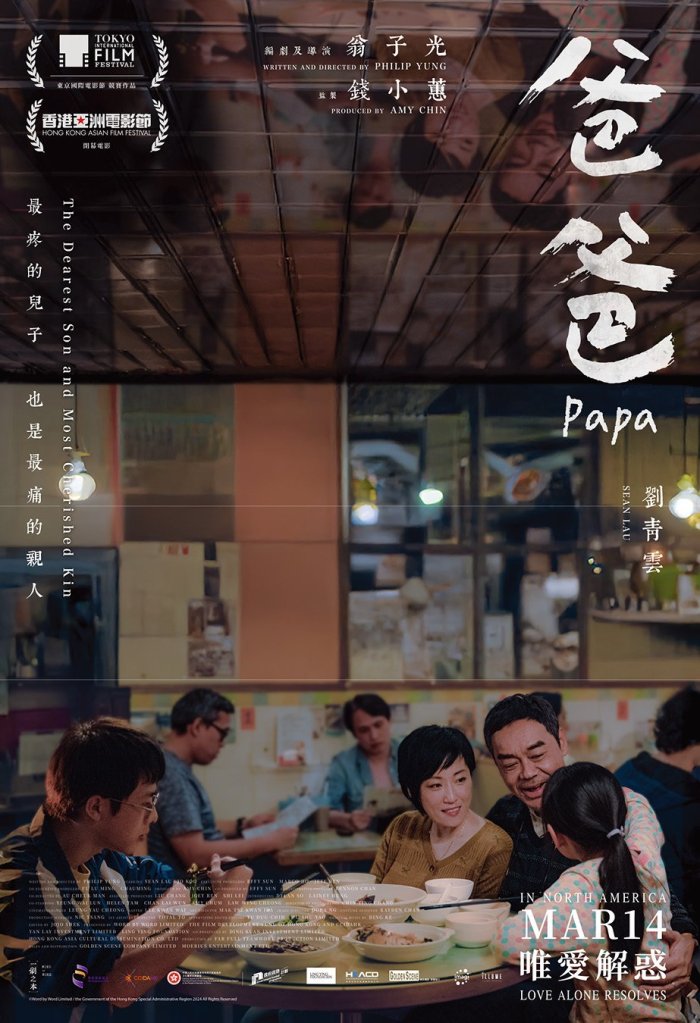

Philip Yung (director), Papa, 2024. 131 min.

Prologue: Watching Hong Kong films overseas is a transposing experience. When I leave a cinema in Toronto after watching a Cantonese film, it often feels strangely surreal to find myself once again surrounded by an English-only world.

Father and son, kin and foe, remembrance and oblivion. As I recall from an Introduction to Linguistics course during my undergraduate studies, toddlers tend to articulate bilabial sounds—such as “mama” and “papa”—more easily as their first words. Calling out to our parents may well be an instinct embedded within us, but learning how to love them—and to feel loved in return—is an entirely different matter, one that may take a lifetime to unravel.

Papa (2024), written and directed by Philip Yung, strikes a deep, melancholic chord—it wounds with sadness, with silence, with absence. Inspired by the 2010 familial tragedy in Tsuen Wan, Hong Kong, in which a teenage boy killed his mother and sister, Papa is no gratuitous B-movie, fascinated with gore or sensational reenactments. Rather, the film’s sombre pacing lingers on the figure left behind—the father of the Yuen family.

Emerging from a working-class background and marrying later in life, Nin (portrayed by Sean Lau) is a man who has never quite learned how to express love—especially not to his son, Ming (Dylan So). He believes that running a 24/7 cha chaan teng—a quintessential Hong Kong-style diner—and providing his family with stability is sufficient proof of his reliability as both husband and father. Though Nin and his wife Yin (Jo Koo) have surmounted differences in age and upbringing, they are ultimately undone by the very family they once forged together. Beneath the seemingly ordinary scenes of family dinners and modest outings, fissures begin to emerge—surfacing like ghosts through Nin’s photo mementos of a life that has already slipped away.

Its storytelling and editing—superbly handled by Jojo Shek—draw the audience into a journey of memory, threaded with unanswered questions and the irreparable consequences that follow the family tragedy. The empty home and untouched bunk bed evoke the Yuens’ most intimate moments: the celebration of their youngest daughter Yan’s (Lainey Hung) birth; the purchase of a brand-new bicycle for a young Ming (Cayson Yeung); Nin catching up with his son along a bicycle path; treasured family time on the coach during their trip to Hainan.

Meanwhile, the film’s non-linear structure interweaves narratives from Nin, Yin, Yan, and even the house cat Carnation (portrayed by Siu Fa), with the unknowable emotional landscape of Ming. As both son and elder brother, Ming is portrayed as a character adrift—alienated from his mischievous classmates, his precocious younger sister, and his emotionally distant parents. The juxtaposition of Ming ascending the stairs at his secondary school with a similar scene at the psychiatric centre underscores his difficulty adapting to the institutions that confine him. Though Ming’s internal voice remains unheard, his parents’ attempts to compensate through material offerings misfire—misunderstanding his needs and further isolating him.

These criss-crossing memories surface intrusively—uninvited but inescapable—for those left grieving. However deeply Nin yearns to remember and relive the moments he shared with his family, he must confront the void left behind: the gaping holes in the sofa following the murders, the unopened letters addressed to his deceased wife and daughter. Caught between imagination and reality, the film delivers heartrending moments as Nin gradually recognises that unless he lets go of his past and his desperate impulse to uncover the truth behind the tragedy, he risks further wounding himself. It is only when he chooses not to press Ming for definitive answers that he is able to move toward reconciliation—with his son, and with himself—protecting Ming from the cold grip of institutional and judicial systems.

I find Papa powerful not for its cinematography or elaborate plotting, but for its quiet sincerity in exploring the terrain of remembering and forgetting. Some say time heals—but for many, time cannot reach the deepest wounds. At times, time behaves more like the digital camera Nin once bought: it captures isolated clicks, fragments of love and loss, fragments that help us remember those we’ve cherished, affirm that we have lived, and remind us—however fleetingly—that we are capable of both loving and being loved.

How to cite: Tam, Tin Yuet. “Papa: Time to Forgive.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 23 Mar. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/04/23/papa.

Tin Yuet Tam is a Hongkonger who writes about arts and culture. She has written critiques on performing arts in Chinese, for example, her theatre critiques can be found in Hong Kong Repertory Theatre’s Repazine. She has also been writing poetry, reviews, interviews, and essays in English. Tin Yuet’s poetry has been featured in Canto Cutie and Voice & Verse Poetry Magazine. When she is not writing, you might find her strolling along the streets for hours just to immerse herself in cities. She currently resides in Toronto, Canada. Find her work on Instagram: @walk_talk_chalk [All contributions by Tin Yuet Tam.]