📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

Click HERE to read all entries in Cha on Ezra Pound’s Chinese Friends.

Zhaoming Qian (editor), Ezra Pound’s Chinese Friends: Stories in Letters, Oxford University Press. 2008. 272 pgs.

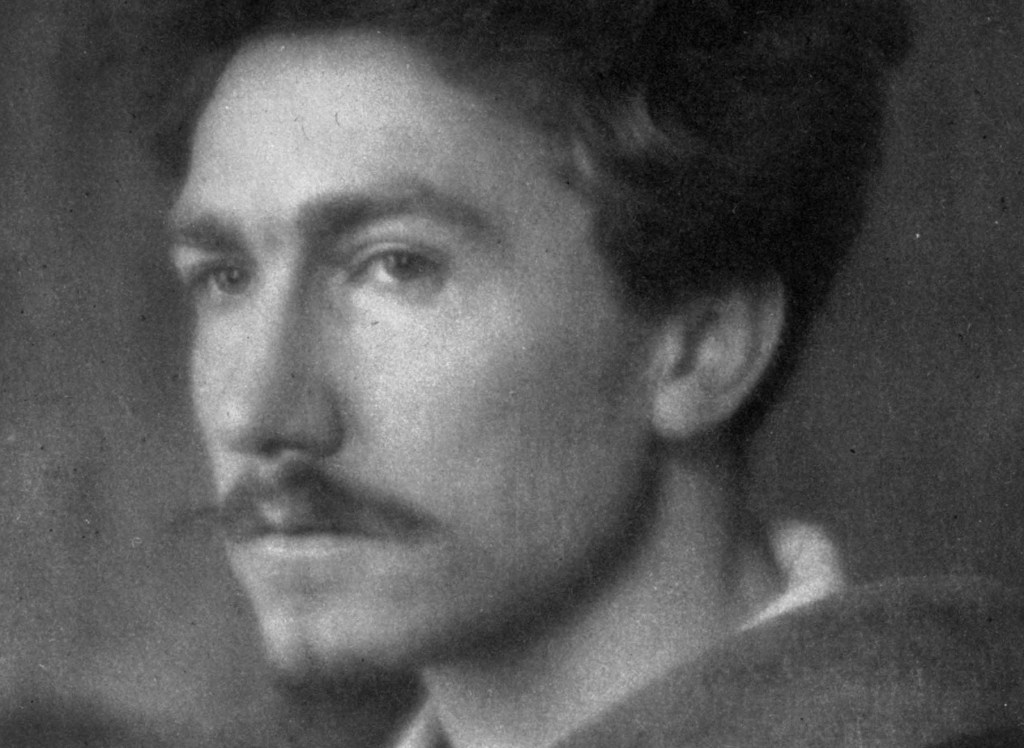

Ezra Pound never set foot in China—yet China is almost everywhere in his work. His multilingual Cantos abounds with references to Confucius, Mencius, and legendary emperors, with the placement of Chinese characters conspicuous even among pages replete with untranslated citations in Latin, Ancient Greek, and Provençal. Like many of his literary contemporaries, the thought—and especially the languages—of the Orient emerged as an alluring counterpoint to the Occidental society in which they moved. But unlike many of his cohort whose interest either faded or was subsumed into a more subterranean form, Pound’s voluminous body of poetry, essays, and letters stands as a testament to a lifelong—indeed, committed—engagement with Chinese thought and poetics.

Pound was twenty-three, ignominiously dismissed from a college teaching post and still uncertain of his future as a poet, with only a few dozen poems in print, when he arrived in London during the summer of 1908. Before long, he became a frequent visitor to the British Museum and there made the acquaintance of Laurence Binyon, an assistant curator of Oriental art. Increasingly interested in China and Japan, the young Pound attended Binyon’s lectures on East Asian art and began to familiarise himself with the work of respected sinologists such as Herbert Giles. It was Binyon who facilitated Pound’s meeting with Ernest Fenollosa’s widow, Mary, who entrusted him with her late husband’s manuscripts. These papers contained records of Fenollosa’s patient study of Classical Chinese texts, undertaken with the guidance of Japanese tutors, which Pound would later edit and publish as The Chinese Written Character as a Medium for Poetry (1919).

This essay served as a foundation for Pound—already steeped in the work of French and British sinologists—to advance a novel, though heavily contested, theory of reading Classical Chinese characters. He asserts that the Chinese mode of expression is fundamentally poetic—concrete and crystalline in its use of images—which stands in contrast to the Western penchant for abstraction. Classical Chinese poetry, then, would pave the way for a renewal of American verse. However, Pound’s own facility with Chinese during this period was dubious at best, and Fenollosa’s insights—having no knowledge of Chinese himself—came by way of Japanese scholars.

This scenario raises a number of thorny issues—terra cognita for scholars examining Pound’s engagement with China. First and foremost—Orientalism. Pound’s translations, collected in Cathay (1915), alongside other poems published in various literary reviews, relied almost entirely on partial drafts and complete translations (often referred to as “cribs” in the vernacular of Pound scholars) produced by earlier generations of sinologists. Giles, once again, appears to have been a significant source.

On one hand, these works are contentious even in their classification as “translations”. Throughout their afterlife, they have been subject to intense scholarly scrutiny, with some egregious errors brought to light. On the other hand, the Anglo-American modernist contingent received Pound’s efforts as a translator with considerably more amity. Yet certain instances of this praise seem to conceal a hint of veiled criticism. Pound’s friend T. S. Eliot famously described him as “the inventor of Chinese poetry of our time”, where the ambiguity of “inventor” simultaneously conveys the poet’s creative brilliance and alludes to the old Platonic indictment of the artist as one who traffics in fabrications.

The ambivalent tenor of Eliot’s phrase—is it praise, condemnation, or both?—also curiously anticipates Edward Said’s notion of Orientalism. In his critique of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Western academic representations of the Near East, Said invokes similar terms when he writes: “The Orient was almost a European invention, and had been since antiquity a place of romance, exotic beings, haunting memories and landscapes, remarkable experiences.” Western fascination with the East, Said suggests, may rest on little more than a phantasmatic conjuration of the Orient—a fictive and serviceable Other against which the Western subject discovers its own Self.

Since Pound’s initial forays into Chinese literature undoubtedly relied almost entirely on scholars of the orientalist mould, it is not difficult to see how his translations were shaped more by his own poetic impulse—and, by extension, more illustrative of a domestication of non-Western modes of expression—than by a concern for fidelity to the Chinese originals. But this image of Pound, steeped in a mixture of Fenollosa and his own misreadings of the latter, is arguably a restrictive frame affixed to a limited moment in the poet’s life. A broader, more historically attuned perspective tells a rather different story.

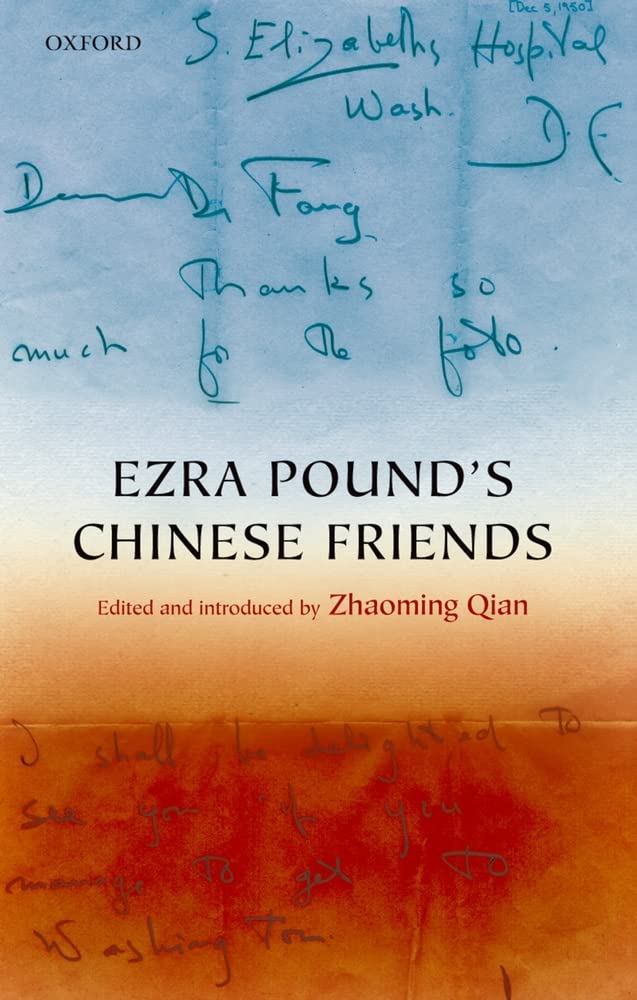

Spanning forty-five years of correspondence between Pound and Chinese scholars and students, Qian’s Ezra Pound’s Chinese Friends is a hybrid work—part curated archive of preserved letters, part scholarly commentary on that archive. Qian also states that the book is intended as a companion piece to his earlier monographs, Orientalism and Modernism (1995) and The Modernist Response to Chinese Art (2003). But whereas his “previous studies forgo personal dramas in favour of intertextual and inter-arts criticisms, this volume brings the influence of China into a lively and powerful social context” (xv). This “social context” draws attention to the individual interlocutors within Pound’s intellectual circle—those who constitute the book’s eponymous “Chinese Friends”.

Qian casts these interlocutors as “friends”—an initially curious term that grows increasingly apt as one progresses through the volume. These friends were not Confucius or Mencius. They were not textual sources but living, breathing individuals—some sycophantic in their flattery of the poet, others speaking past him entirely, and still others in near total simpatico. The volume’s 162-odd letters articulate the meaning of “cultural exchange” in its fullest range—not as a one-sided commerce of ideas, but as a complex process of mutual cross-pollination. Pound, too, reveals a diverse array of refractions of his personality: the Westerner ignorant of modern Chinese history and politics; the diligent student of written Chinese; the irascible, unrepentant bigot; and the insightful poet and virtuoso of his craft.

Each section centres on an individual friend, further underscoring the emphasis on Pound’s specific social relations—from F. T. Sung (who teasingly dangled the prospect of securing Pound a job in China) to P. H. Fang (a Boston College professor and Lijiang native who appears to have imparted much knowledge to Pound about the Naxi people).

Much as Pound once described Fenollosa’s notes as a “goldmine”, Pound scholars may discover a variety of rich veins to mine within these letters. Broadly speaking, one can discern three distinct motifs within Pound’s relationship to China. First, there are his controversial translations of Chinese poetry and his ideogrammatic theory; second, his translations of Confucian texts and the influence of Confucian thought on his political and economic theories; and finally, the incorporation of Chinese figures and Confucian ideas into his poetry—particularly The Cantos. Qian’s book offers relevant material for all three of these areas.

For instance, Pound’s letters to Achilles Fang—a Chinese graduate student and later a lecturer on Chinese humanities at Harvard, who wrote a dissertation on Pound and collaborated with him on his Shijing translation—provide further evidence of a shift in Pound’s earlier views on the Chinese writing system: “Total impossibility to form any idea of REAL sound of any language save by HEARING it spoken…. For years I never made ANY attempt to hitch ANY sound to the ideograms/ content with meaning and the visual form” (77).

In another set of exchanges with Angela Jung, a PhD student working on a dissertation on Chinese themes in The Cantos, Pound asked her to evaluate his attempt at composing in Chinese characters. This correspondence reveals a subtle note of pained humility, as he confides that another friend—Achilles Fang, as it turns out—had found his poem lacking the intended sense: “Dear Miss Jung, I have a friend who really knows, & who says my little poem <vide infra> can’t possibly mean what he thinks I want it to mean. If you really want to help me you might tell me what you think it means, if it makes sense @ all.” The letter ends on a note of frustration familiar to any student of foreign languages: “The other problem would be: how many more ideograms would I have to add to make my meaning clear if it is possible to get @ it.” (93).

Qian observes that this neophytic attempt at composing Chinese poems in Chinese characters anticipates a fragment Pound later includes in Canto 110: “(月 明 莫 顯 朋 or ‘moon bright not appear friends’)” (89). Alongside Pound’s discussions with Achilles Fang on the peculiarities of specific Confucian terms—such as jing 敬, or “respect”, and the four tuan 四端, or “the four seeds” of virtuous human conduct—these asides underscore the exegetical value of the book. Since its publication, it has served scholars as an indispensable resource, offering insight into both the depth and the limits of Pound’s knowledge of Classical Chinese, as well as providing precise references to his textual sources—e.g. Mathews’ Chinese-English Dictionary or Legge’s translations of Confucius—enabling a more informed reading of the Chinese references embedded in his poetry.

The final set of correspondence, with P. H. Fang, attributes Pound’s later interest in the Naxi people and Lijiang to Fang’s influence. Scholars had previously identified Joseph Rock—the Austrian-American botanist and ethnographer—and Peter Goullart as Pound’s primary sources on the unique Naxi culture and its remarkable pictographic script (known as Dongba). However, Qian—who interviewed P. H. Fang personally for this project—sets the record straight, presenting Fang, a native of Lijiang, as Pound’s assuredly corporeal Naxi tutor.

Qian offers an illuminating perspective on Pound’s trajectory in relation to his engagement with China. If the poet began in the 1910s by relying on orientalist sources, by mid-century he was clearly far better informed, drawing on a range of autochthonous voices. Yet a full abrogation of the orientalist spirit seems persistently elusive. In response to the critiques of his Chinese poem by Achilles Fang and Angela Jung, a defensive Pound was quick to fall back on his long-standing convictions: “ideogram INCLUSIVE, sometime not the least ambiguous but ideogramic mind not always trying to split things into fragments” (94). Moreover, there is the highly speculative—yet irresistible—notion that his interest in Naxi pictographs reveals a preference for a form of Chinese orthography more amenable to the pictographic theories he had held since Fenollosa.

Pound’s China presents another tension: his exclusive focus on the Confucian classics and ancient Chinese writing systems coincides with a period in which those very same aspects were undergoing contentious scrutiny within a Chinese literary scene in the midst of modernisation. For Pound—as for so many of the classic orientalists—the allure of the non-Western subject resided in its value as a pristine image of enlightened antiquity, in its foreignness that served to defamiliarise Western culture, and in its ultimate utility as a comparator for self-measurement.

Qian explicitly invokes Said and Orientalism in one of his earlier monographs, Orientalism and Modernism (1995), wherein he both extends the concept to encompass China and Japan, and reconfigures its portrayal of European engagements with the East—not as reductively supercilious, but also as bound up in the art of imitation. Qian’s reformulation of Said’s Orientalism can be traced to a precursor in Goethe and his dream of a multicultural Weltliteratur. He excavates the lesser-considered dimension of symbolic power (without diminishing the significance of its concrete, imperial manifestations), prompting us to question the presumed wholeness or purity of the Western writing subject. If Pound’s modernist poetic project is—as it appears—inflected by Chinese influences, then the Poundian China might be understood as a dialectical product: an Other that exists within the Western modernist Self.

Consequently, any perspective on Pound’s relationship with China must remain necessarily complex—marked by an almost compulsive concern for the accuracy of meaning, yet accompanied by equivocation and, at times, nearly unforgivable misreadings. This perspective, as Qian’s book makes clear, contributes to ongoing academic debates that interrogate the viability of current models of world literature. “Whose world literature?” is both a central provocation and a critical prompt, generating rich contrapuntal explorations—postcolonial, decolonial, and those concerned with the problem of monolingualism, to name just a few avenues. Pound’s correspondence in this volume reminds us that his misreadings of Chinese history and language should not be dismissed as distortions tout court but may, in fact, be understood as productive misreadings in their own right.

Ezra Pound’s Chinese Friends offers no earth-shattering revelations. Yet it stands as an essential work of archival scholarship for readers interested in Pound’s intellectual engagement with China. Qian himself would likely agree with this assessment, having since gone on to elaborate these “social contexts” in later academic articles and his subsequent monograph, East–West Exchange (2017), which expands the field to include lesser-known accounts of other modernist poets and their Chinese interlocutors—William Carlos Williams and David Rafael Wang’s collaboration on “The Cassia Tree”, Marianne Moore and Mai-mai Sze, among others.

Perhaps the most impressive quality of Qian’s scholarship lies in its ability to inspire a return to The Cantos—better equipped, perhaps, to bracket the notion of Pound’s ignorance (in his own words, that of the “useless barbarian” with respect to Chinese), and instead to read his borrowings as the utterances of an earnest student of Confucian language, and of the poetics of the great practitioners of the classical Chinese tradition.

How to cite: Fan, Andrew. “”Eastern Liaisons: Ezra Pound’s Chinese Friends.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 16 Apr. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/04/16/pound.

Andrew Fan is a PhD student in the Comparative Literature department at the Graduate Center, City University of New York. He is currently working on a dissertation exploring narrative temporality in cinema and in the fiction of Henry James and Marcel Proust.