📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

Steven Schwankert, The Six: The Untold Story of the Titanic’s Chinese Survivors. Simon & Schuster, 2025. 240 pgs.

When the transatlantic ocean liner RMS Titanic struck an iceberg and sank on 15 April 1912, one passenger clung desperately to a floating piece of debris. Washed by the frigid waters of the North Atlantic, death was but moments away—until the splash of a lifeboat’s oars drew near.

For the untold millions who have seen James Cameron’s 1997 blockbuster Titanic, the scene is a familiar one. But this was neither Rose nor Jack—it was Fong Wing Sun, a young seaman from the Taishan region of Guangdong province. His extraordinary tale of survival would later become one of cinema’s most iconic moments and inspired American author Steven Schwankert to unearth the true stories behind the doomed liner’s six Chinese survivors.

According to lurid newspaper reports and certain passenger testimonies, the men had stowed away on lifeboats or disguised themselves as women, surviving only at the expense of more “deserving” passengers and the noble Anglo-Saxon men who went down with the ship. But how much of this narrative withstands scrutiny—and how much is a hateful fiction born of anti-Chinese racism and a grieving public’s desperate search for scapegoats?

Schwankert’s new book The Six: The Untold Story of the Titanic’s Chinese Survivors delves into historical archives and draws upon original scientific experiments to address these questions. Based on the documentary of the same name by Schwankert and filmmaker Arthur Jones, the book also uses the facts and myths surrounding these men to tell a broader story—of China’s place in the maritime world of the 20th century, of the global Chinese diaspora, and of survival against the odds.

Schwankert was recently in Hong Kong for the city’s International Literary Festival. I asked him six questions about The Six—and one more about his future research plans.

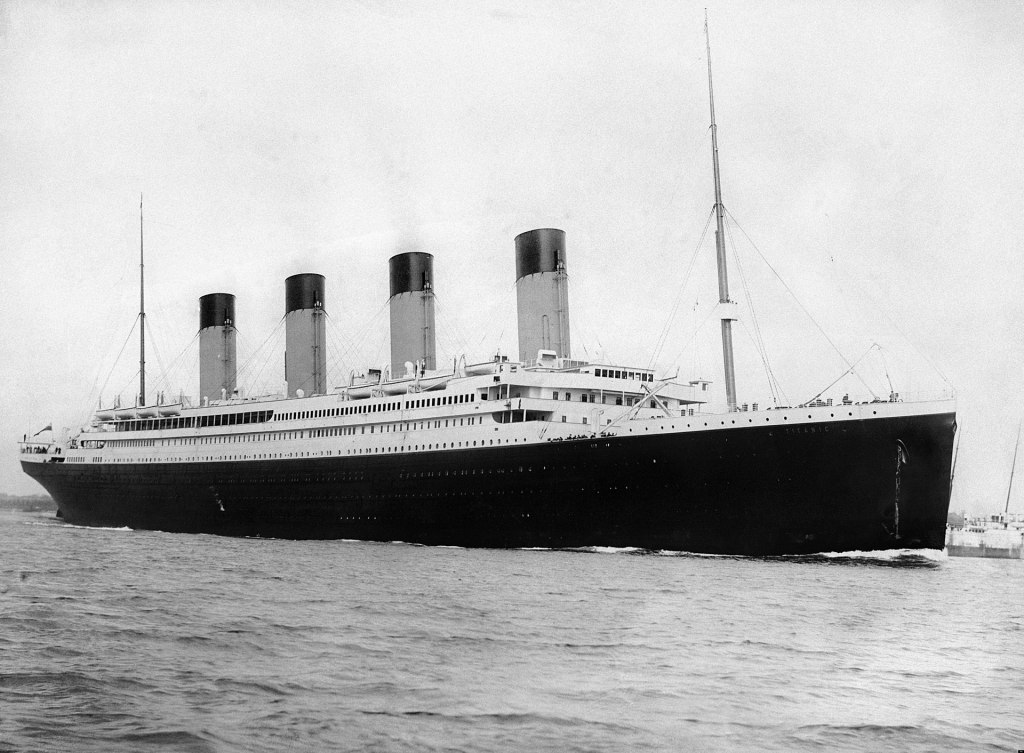

The Titanic, showing eight lifeboats along the starboard-side boat deck (upper deck): four lifeboats near the bridge wheel house and four lifeboats near the 4th funnel (via)

Ryan Ho Kilpatrick: The story you weave in The Six encompasses far more than the lives of six men or a single ship. It touches upon immigration and the diasporic experience, anti-Chinese racism in the United States and beyond, the turbulence of twentieth-century China—and more. What would you say are the broader themes and lessons you hoped readers would take away from the book? How would you appeal to those who may not possess a particular interest in maritime history?

Steven Schwankert: The Titanic is just a quickly identifiable peg on which to hang a story about the Chinese diaspora in the first half of the 20th century. We could have picked any eight men who started from a common point and emigrated to find work, but the Titanic is easily recognisable and perhaps a bit dramatic. They are buffeted by the currents of history, first from China to Europe, and then back and forth across the Atlantic—initially due to trade, then by the First World War and its aftermath. That they end up in different places with different outcomes tells us a lot not only about them, but also about the way the UK, the US, Canada and other countries treated Chinese immigrants during that period.

Ryan: You write about how, at the outset of your research, knowledge of these six men—and even a basic curiosity about their story—was limited in both China and the West. One particularly memorable example is the Titanic expert who uncritically accepted the slanderous myth that they were stowaways, without so much as questioning whether it was even physically possible. Has this changed in the years since the documentary was released? Do you believe there is now greater awareness of—and perhaps even sympathy for—what they endured?

Steven: I think there is a growing interest and curiosity in stories like theirs. There is also a significant body of research into the Middle Eastern passengers on the Titanic—people who believe their relatives or friends were shot to death by the ship’s crew. The fascination with the Titanic is so enduring that there is a desire to uncover every dusty corner of its history, and we just happened to stumble into one of the dustiest.

Ryan: What was the most memorable or significant discovery you made during the course of researching the six? For me, it may have been the relationship between Fong Wing Sun and the two casualties among the eight, who had planned to go into business and begin new lives in America—it was such a profoundly humanising detail.

Steven: Reading that article about Sue Oi, the lovelorn fiancée of one of the two Chinese victims, revealed so much. We still don’t fully understand the relationship between Fong Wing Sun, who survived, and Lee Ling and Len Lam, who didn’t. But clearly, they knew each other and had a plan to become merchants in the American Midwest. It explains why all three of them ended up in the water—they had a plan, and they stuck together. Floating on wreckage, freezing and alone, Fong Wing Sun’s friends died, and his possessions and money went down with the ship. He lost everything except his life. But he survived and started over. Knowing his son and grandchildren, it is remarkable to see the fruit that perseverance has borne.

Where these men appear in the broader Titanic story sheds light on many aspects of that history. J. Bruce Ismay, the owner of Titanic, tried to distance himself from them in his testimony to the U.S. and British inquiries. Yet the presence of four Chinese survivors in the same lifeboat actually supports his account—their being able to board that lifeboat suggests there weren’t crowds around attempting to get on, and by extension, that neither they nor Ismay survived at the expense of any women or children. By knowing their story, we gain a fuller understanding of the entire Titanic tale.

Ryan: At numerous points throughout the book, I found myself wishing that someone had asked the six about their stories—or that they had shared them with someone of their own accord. It is regrettable that no journalists during their lifetimes ever sought them out, and that they left behind no firsthand accounts for the historical record. Why do you think this was the case?

Steven: Journalists often catch all the blame for not reporting their story, but I’m not sure they were ever particularly keen to tell it. Lee Bing mentioned it a little. Fong Wing Sun appears to have written about it in a diary that went missing shortly after his death. I’m not convinced the average person wants their life story recorded or widely known—that’s the norm. Most importantly, while we may see their Titanic story as important or interesting, I’m not sure they did. The story of their lives is about overcoming obstacles. Whatever the challenge—whether it was finding employment, a sinking ship, exclusion laws, or anything else—they met it and overcame it. Their lives were filled with icebergs. They just became rather good at swerving around them.

Ryan: In the closing chapters of your book, we are given a fascinating behind-the-scenes glimpse into your research process and the team that supported it. Was the experience markedly different from what you had anticipated—or from previous projects you have undertaken, such as Poseidon? Do you have any salient advice for those embarking on a project of this nature?

Steven: The process was slightly unorthodox. Because Arthur Jones, who directed The Six documentary, wanted to capture any eureka moments or frustration on camera, there were times when I would set the research team working on something, but wouldn’t find out the results until the next time we filmed. Our researchers were fantastic, but occasionally I felt in the dark, while members of the team were already ready to move on to the next thing.

For would-be researchers: public records, where accessible, are your friends. Some searches are stymied because records have been destroyed, are locked away, or have been misplaced. But for the most part, the jigsaw pieces are all there—they may just be scattered around the world rather than poured out on a kitchen table. The other thing I would say to researchers is: whenever possible, go and get the original records. Scans are great—they’re convenient and inexpensive—but the physical files tell you things. Look at the handwriting. Check for notes in the margins that may not have come through in the scans. See what’s been stuffed into the file and falls out—something that perhaps wasn’t scanned or catalogued. Those pieces of paper can reveal a lot, if you can put your own eyes and hands on them.

Ryan: The Six answers many questions—but not all. One of the lingering mysteries you explore is burial plot 233 at Fairview Cemetery in Halifax, Nova Scotia, which may be the final resting place of one of the Chinese victims. However, the latest DNA testing technology has not yet been approved for use at the site. What are some of the other questions you still hope to see answered, and are we any closer to uncovering the truth now?

Steven: Well, we have quite a few questions that remain. I’d love to know why Lee Bing decided to leave the town of Galt, Ontario, around 1942—and return to wartorn China. The ultimate fate of a couple of our survivors makes me wonder. It’s not easy to find people who were not intending to leave any trail of breadcrumbs behind. Still, it would be nice to know what happened to them. I’m surprised that no significant leads have surfaced since the documentary came out. Maybe the book will expose the story to a different audience and make that connection. I didn’t believe at the beginning that their stories didn’t exist and weren’t recorded or remembered—and I still don’t believe it.

Ryan: Finally, I was hoping you might share a little about what lies ahead for you. Do you still intend to pursue something on the SS Kiangya—or have other shipwrecks since captured your interest? Are there any other major, untold stories in Chinese maritime history that come to mind?

Steven: There are lots of big untold stories in China’s maritime history, especially in the first half of the 20th century, that I’ll never have the chance to write. I’ll be returning to the story of Kiangya to finish that up. It was a great story when we started on it, and it still is—it just isn’t known in English at all. After that, I’m going to work on an Asian American story. I love it because it requires nuanced thinking and consideration—which means that, along the way, it will really make people upset, which is great. History is a lens that may help us see past events more clearly, or it may distort them. We should not be afraid to bring those events into focus, and no good end is served by allowing them to be blurred.

How to cite: Kilpatrick, Ryan Hok. “Six Questions about the Six—Steven Schwankert’s The Six: The Untold Story of the Titanic’s Chinese Survivors.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 14 Apr. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/04/14/chinese-survivors.

Ryan Ho Kilpatrick is an award-winning journalist and writer from Hong Kong. He has previously served as Managing Editor of the China Media Project and worked as a reporter for TaiwanPlus, The Washington Post, Hong Kong Free Press, TIME, and dpa. A divemaster as well as a seasoned paddler and sailor, he has a particular interest in the maritime history and culture of Hong Kong and the surrounding region. You can find his website and portfolio here. [All contributions by Ryan Ho Kilpatrick.]