📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

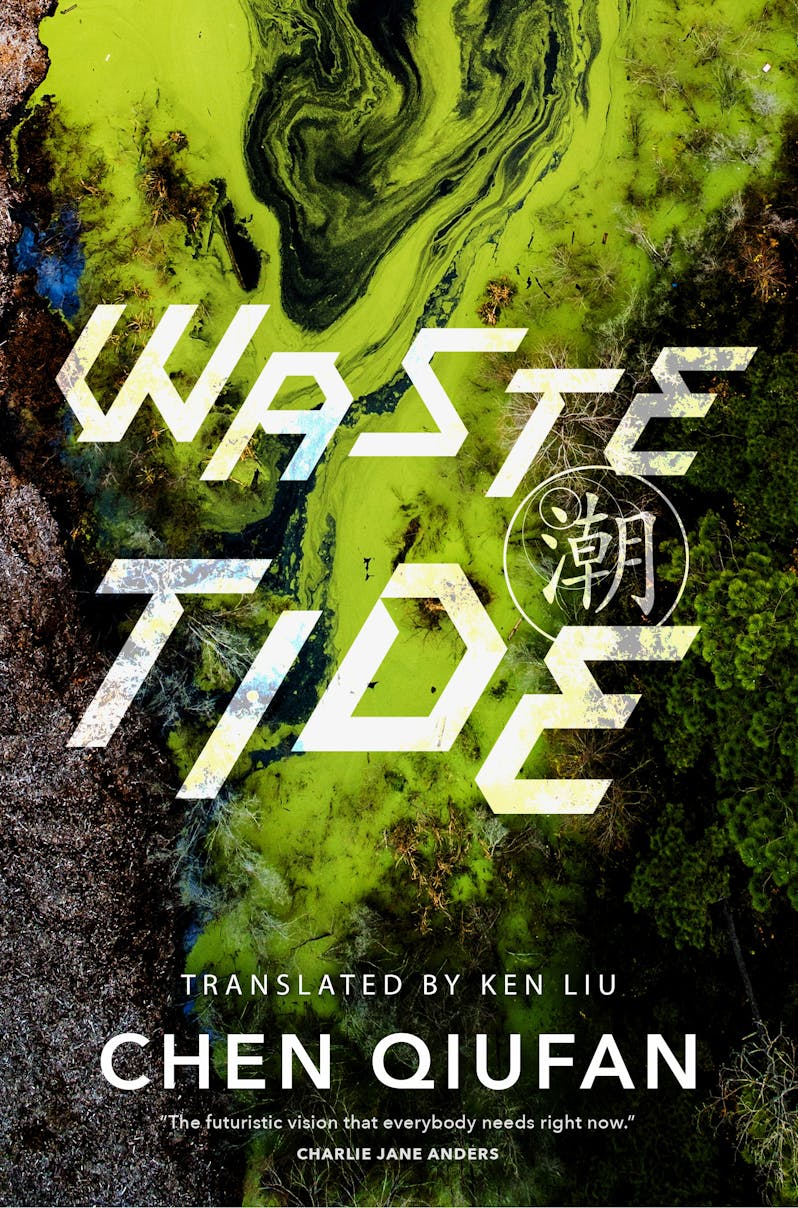

Chen Qiufan (author), Ken Liu (translator), Waste Tide, Tor Books, 2019. 352 pgs.

They call us “the waste people.” Waste is dirty, inferior, lowly, useless, but omnipresent. They produce waste every day; they can’t live without the waste people. (142)

Written by Chen Qiufan and translated by Ken Liu, Waste Tide is a sci-fi thriller that certainly sends chills down one’s spine—not only for the harrowing, dystopian future it envisions within the world of waste, but also for its incisive observations on global politics and the everyday realities of waste pickers today.

The narrative unfolds in Silicon Isle, a fictional region in southern China that serves as the world’s dumping ground. Here, people make a living from—and live amidst—vast mountains of electronic waste transported from across the globe. The area is governed by a complex political mélange of the local government and three dominant family clans—Luo, Chen, and Lin—with the Luo clan occupying the central role. The Luo are portrayed as the most powerful, both economically and politically, deriving their dominance from controlling the island’s largest e-waste dismantling workshops. When shipping containers arrive at the port, the Luo clan have first pick of the waste, before the remainder is divided between the other two clans.

The narrative primarily centres on a waste girl named Mimi, who begins as one of the countless anonymous workers on the island. However, as the plot progresses, Mimi becomes a pivotal figure in multiple subplots—each threaded with a sinister undertone, hinting at a larger, more dangerous force that threatens all life on the island.

The living conditions of Silicon Isle’s waste workers may appear as an extreme extrapolation of the hardships faced by present-day waste pickers—but the story reads as a cautionary tale of what could come to pass, or perhaps as a grim acknowledgement that certain inequalities are, regrettably, enduring. Even within the dystopian landscape of Waste Tide, the waste people continue to endure injustices uncannily similar to those documented in works such as Katherine Boo’s Behind the Beautiful Forevers. As a researcher focusing on waste and livelihoods in urban contexts, I saw many parallels with the experiences of waste pickers I encountered in India. Chen deftly captures the class dynamics of a waste settlement, as well as the stigma and psychological burden that waste pickers frequently confront.

You are nothing but a WASTE GIRL. The label had been branded in her heart more securely than the film applied to the back of her neck, impossible to erase. All of her actions and choices had been circumscribed by that label, an invisible line that she had not dared to cross. (174)

The author’s capitalisation of “Waste Girl” evokes the image of a searing, red-hot iron brand—etched into the souls of the waste people to suppress and extinguish any sense of personal identity, opinion, dignity, or self-worth. In their marginalised status, burdened by the stigma of waste work, the waste people are compelled to kneel and beg for mercy from the natives because “they had dirtied his clothing, unintentionally stared at him for too long, touched her child, brushed against his car, or even for no reason at all, simply because they were waste people” (p. 187). In response to these conditions, Chen offers a powerful quote that cuts to the heart of the class politics still faced by waste pickers today:

[The Silicon Isle natives] stood, heads slightly lifted, as if they belonged to a completely different species whose birthright was to gaze down upon these people like animals, upon these people who were no different from themselves whether by genes… [the waste people] sacrificed their health and lives in exchange for insignificant scraps to fill their bellies and distant dreams, built up the extravagant prosperity of Silicon Isle, and yet they were seen as only slaves, bugs, disposable trash. They were forced to watch it all with numbed gazes. (187)

The world in which the waste people lived was also deeply polluted. Metal chassis and broken circuit boards lay strewn across the landscape, and the air hung heavy with the acrid stench of burning PVC and circuit boards—an atmosphere that stung the nose. People washed their clothes in blackened water, while children played on beaches stained dark, littered with fibreglass fragments and scorched electronic debris. The toxins were so pervasive that even the seafood displayed strange mutations. The waste people worked without protective gear, often burning plastics and inhaling the toxic fumes in order to distinguish one type from another by scent.

According to an account by Chen, these vivid descriptions were inspired by his own experience visiting Guiyu. Chen grew up in Shantou County, home to Guiyu—one of the world’s largest centres for e-waste processing. Reflecting on his visit, he remarked how “his eyes, skin, respiratory system and lungs were all protesting against the heavily polluted air”. It was one of the formative experiences that compelled him to write this debut novel, rooted in his hometown. In Chinese, Silicon Isle is rendered as 硅屿 (gui yu), which shares the same pronunciation as 贵屿 (Guiyu).

Returning to the earlier quotation—“bugs” as the waste people may be—we witness in Parts II and III of the novel just how powerful they become as a collective. The natives generate waste and derive economic power from the dirty work the waste people perform. Waste is omnipresent—and so are they—and in this very ubiquity lies their strength. Mimi rises as a leader and central figure in the uprising—“an oracle bringing a message from the spirits: a person lives not just for the fact of existence itself” (143).

In Waste Tide, Chen also explores the politics of the global waste trade in a strikingly realistic manner—stripping away the glossy veneer of development aid schemes. Aside from Mimi, another significant character is the Caucasian American, Scott Brandle, a purported representative of the firm TerraGreen Recycling, who arrives to propose a recycling industrial project to the local government and political powers on Silicon Isle.

The plan is tailored to appeal to the local government’s aspirations for social stability and economic growth. The proposal involves the government providing land for the establishment of an industrial park dedicated to recycling. TerraGreen Recycling would contribute the technological expertise, while the government would collaborate with the ruling clans to integrate existing waste management practices into the new industrial complex—ostensibly creating jobs and stimulating the local economy. These promises are wrapped in the rhetoric of environmental restoration, pledging to “return [their home] to a former glory: blue skies and clear water” (24).

Yet the proposal fails to gain support from any party. One of the characters, Director Lin—who serves in the government and is also a member of the Lin clan—delivers a blunt truth to Scott: no one truly cares, neither the natives nor the waste people, all of whom are migrants.

The natives don’t care. They just want to squeeze as much money as they can out of whatever life is left in this place. The migrant workers don’t care, either. They just want to earn enough money as quickly as possible to return to their home villages and open up a general store, or build a new house and get married. They hate this island. No one cares about the future of this place. They want to leave here and forget this period of their lives, just like the trash. (24)

Earlier parts of the novel underscore the irony of the proposed project on multiple occasions—namely, the Americans’ treatment of places like Silicon Isle as private landfills, only to arrive with proposals to clean up the environment and render waste management more efficient. As the story unfolds, a more sinister subplot emerges behind the recycling industrial initiative—one involving what is described as “the witch’s magical dust in fairy tales”: rare earth metals. The discussions surrounding TerraGreen Recycling’s intentions prompt reflection on the current politics of the global waste trade.

A prominent theme running through the novel is technology. In this dystopian, transhuman world, technology is intricately embedded not only in everyday life but also within the human body. Amidst the towering mounds of e-waste, the waste people scavenge discarded prosthetic limbs and attach them to themselves. Other augmenting technologies are also present—muscle-enhancing mechanisms, neon films that adhere to the skin like tattoos, and more. Through this, Chen interweaves complex and searching meditations on the overwhelming presence and power of technology. It is as ubiquitous as waste itself. Technology can empower, but it can also destroy. It can enhance lives—yet equally, it can degrade them.

I felt numb after finishing Waste Tide. I remember taking a deep breath upon turning the final page, needing a moment of stillness to let it all sink in—to allow those thoughts to settle and brew. There was so much to absorb, and admittedly, the sheer number of characters and organisations made the narrative difficult to follow at times. Nevertheless, it is a brilliantly crafted novel that poses deeply thought-provoking questions about waste, technology, class conflict, politics, and more.

It was only while writing this review that I came to realise what, for me, was the novel’s most compelling thematic thread. Subtle and unassuming—yet perhaps the most powerful of all—it lies in the framing of the story. The prologue opens with a destructive typhoon that sinks a boat led by a complex environmental activist, who reappears sporadically throughout the novel. Fittingly, the book closes with another devastating typhoon—one that sweeps the chaos into a violent silence, erasing all traces of what came before.

Perhaps it is fitting to end this review with that thought—a lingering question about our techno-environmental futures.

How to cite: Chan, Loritta. “A Harrowing Future of Waste in Chen Qiufan’s Waste Tide.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 8 Apr. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/04/08/waste-tide.

Loritta Chan is a researcher based in Hong Kong, specialising in children and young poeple’s livelihoods, waste, and sustainable urban environments. She holds a PhD in Human Geography from the University of Edinburgh, where her dissertation focused on the lives of children and young people from waste-picker families in Delhi. In the years that followed, Loritta held postdoctoral fellowships in both the UK and Hong Kong, contributing to projects on inclusive cities for young people as well as water conservation. Outside of her academic work, Loritta enjoys illustrating, reading poetry, and taking long walks. [All contributions by Loritta Chan.]