📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

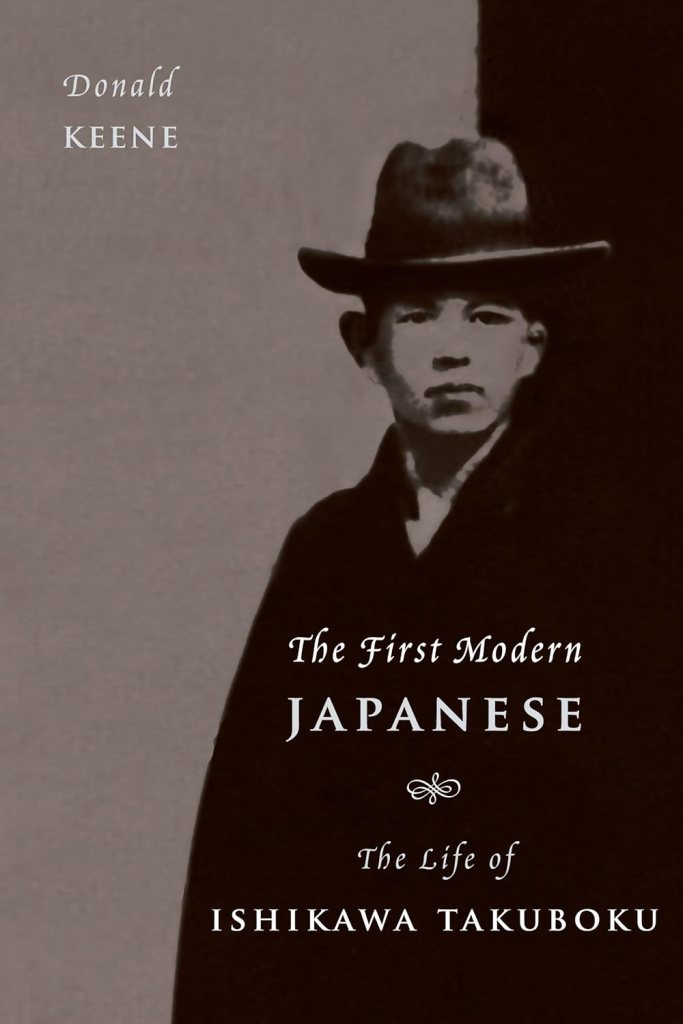

Donald Keene, The First Modern Japanese: The Life of Ishikawa Takuboku, Columbia University Press, 2016. 288 pgs.

At the age of fifteen, I first encountered the Chinese translation of Ishikawa Takuboku’s collection of tanka. The line from A Handful of Sand—“the taste of things—I knew it / all too soon”—was chosen as the title for this translation. From this line alone, one could grasp the poet’s genius and precocity. At that age, when reading was centred around myself and served primarily my own inner world, the author’s biography seemed of relatively little importance. To feel his joys and sorrows, to partake in his anger and melancholy—it followed naturally that I would come to regard the poet as my contemporary.

Donald Keene’s biography of Ishikawa Takuboku bears the title The First Modern Japanese. This strikingly provocative claim originates with Keene’s predecessor, the philosopher and historian Kōsaka Masaaki. Yet it is not a rigorously argued academic conclusion so much as an intuitive judgment—one that, in fact, resonates deeply with my youthful impression: “In the modern world, we find that Takuboku is, in essence, one of us.” It seems unwise to make definitive pronouncements about any transitional figure in literary history. Navigating between the old and the new, such figures must inevitably heed the intellectual currents of their time and are invariably caught in their sway. They are, of course, products of their era—but they are also individuals: flesh-and-blood beings concerned with livelihood, love, conflict, and suffering. Even in a life as brief as Takuboku’s, his literary convictions and political positions remained in flux—at times shaped by social conditions, at others stirred by the work of fellow writers, and often constrained by material necessity. Thus, after presenting this evocative title, Keene’s choice was to return the biography to its most fundamental and honest form: to trace, as faithfully as possible, the trajectory of Takuboku’s literary output and his social entanglements, while portraying with candour both his tenderness and pride, as well as his confusion and inner turmoil.

Biography can be an art of enchantment. Before reading this book, one could scarcely imagine how, at seventeen, Takuboku—despite having had few opportunities to hear music—was already serialising Wagner’s Thought in a regional mainstream newspaper, striking directly at the heart of cultural, philosophical, and political ideals. A poet whose literary life spanned scarcely a decade, his existence resembled a train hurtling forward at full speed. In years when inspiration surged, he could compose over fifteen hundred tanka in a single year, with little of the tortured heroism we often associate with artistic creation—his poems appeared to arrive as effortlessly as breath. As he struggled to make a living, he moved restlessly from one job to another, drifting between newspapers and magazines. Each of these episodes distilled the local atmosphere, the tangle of human relationships, and the unruly surge of his emotions—none was ever quiet or unremarkable. Most astonishing of all, perhaps, is that no matter how destitute or desperate his circumstances, there were always friends at his side, giving selflessly in his darkest hours. Perhaps it was the force of his genius that inspired such loyalty—a belief, unwavering, that one day the world would recognise the brilliance they had already seen.

And yet, in another sense, biography is also an art of disenchantment. For those familiar with Takuboku’s verses—so often tender in their expressions of love for his mother, wife, child, and friends—it may be difficult to reconcile such warmth with the poet’s lived reality: a man marked by volatility, sexual excess, a bent toward self-destruction, and, perhaps most unsettling of all, a chilling indifference. Though he seemed destined to write tanka all his life, Takuboku never fully embraced poetry as a vocation. His literary career was punctuated by failed attempts at fiction, and despite his reverence for the great writers of the West, he repeatedly found himself ensnared by the limitations of his own experience and an inability to imagine compelling characters. Poetry, for all its beauty, held no economic value for him. The unresolved burden of financial insecurity haunted him throughout his life, leaving him anxious and tormented. His diaries and essays on poetry reveal that his literary ideals remained far from realised. He possessed singular insights into the future of language, the potential evolution of tanka, and the possibilities of fiction—but lacked the means to pursue them, and did not live long enough to break through the constraints that bound him.

Keene’s biography of Ishikawa Takuboku prepares the reader to confront a poet’s most unvarnished desires and defeats. One may find oneself swept up in Takuboku’s anguish with the intimacy of a contemporary, while at other times maintaining a necessary distance—an allowance for clarity, for contemplative detachment. This, perhaps, is an aesthetic and intellectual experience altogether distinct from reading his poetry alone. And yet, when all is said and done, the book does not forget to move the reader. In the end, Takuboku himself was willing to concede that tanka remained a blessing—for anyone unwilling to dismiss those moments in life when emotion overflows. More than a century later, the reader too may come to embrace all that he refused to disregard.

How to cite: Chen, Jiahe. “A Poet’s Most Unvarnished Desires and Defeats: Donald Keene’s The First Modern Japanese.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 13 Jan. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/04/07/first-modern-japanese.

Jiahe Chen, born in 2001, holds a Master’s degree in Sociology from Sciences Po Paris (Paris Institute of Political Studies). Her research centres on cultural industries and gender politics within the Sinophone world. In her spare time, she writes poetry, essays, book reviews, and fiction. Her work has been published in Chinese magazines and platforms, including West Lake and Literaturecave. Some of her pieces have also received recognition in “underground” literary competitions. [All contributions by Jiahe Chen.]