📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

Hideko Abe, Queer Japanese: Gender and Sexual Identities through Linguistic Practices, Palgrave Macmillan, 2010. 199 pgs.

Queer Japanese: Gender and Sexual Identities through Linguistic Practices offers readers a glimpse into a world of ephemera and conversation to which they might not otherwise have access.

In Chapter One, “Queer Etiquette?: Advice Columns with a Difference,” Hideko Abe draws upon a fascinating source: post-1990s periodicals aimed at queer Japanese audiences. Abe’s analysis is not confined to a single magazine or a singular type of queer reader; rather, this chapter compares four distinct publications, each catering to a different demographic. These were magazines that people turned to for advice—both in seeking and offering it. As Abe observes, “Advice columns assume an imagined community where sexual minorities live, interact, exchange, and negotiate their everyday lives.” From this perspective, advice columns from that era appear to have served a function not unlike that of today’s online forums. Whether in print or digital form, advice columns provide a means through which queer individuals can better understand themselves and one another—and feel less isolated in the process. In what Abe terms “the straight world,” heteronormative etiquette and social conventions are either overtly enforced or passively assumed, while queerness remains taboo—something to be stigmatised, suppressed, or ignored. Those who do not conform to heterosexual norms often have to resort to indirect forms of communication in order to navigate and articulate vital aspects of their daily lives. In this context, magazine advice columns offered queer individuals—particularly those unable to speak openly—a discreet yet meaningful channel through which to explore and construct their own understandings of etiquette. In doing so, they were able to connect, express, and ultimately feel less alone.

While both Anise and Carmilla are targeted at young women, they adopt markedly different approaches. Anise—edited by what Abe describes as “young and inexperienced” individuals—conveys a sense of ambivalence and uncertainty, reflected in its cute, girlish aesthetic. In contrast, Carmilla is more explicitly sexual in tone, “not unlike gay men’s magazines” in its presentation. The other two publications, Bádi and G-men, are both overtly sexual in nature, though they differ in style—Bádi favouring slender, fashion-conscious models and a more stylised prose, while G-men features tougher, more muscular figures, evoking a hypermasculine aesthetic. Yet neither is confined solely to sexual content. Both expand into broader themes common to mainstream magazines aimed at heterosexual audiences, including lifestyle, health, and astrology—suggesting a more holistic engagement with queer readership beyond desire alone.

As an English-language reader with no other means of accessing such magazines, this chapter proves particularly compelling. Engaging with it feels akin to watching someone assemble a collage—cutting and pasting fragments from old publications to create a vivid and revealing portrait of queer life.

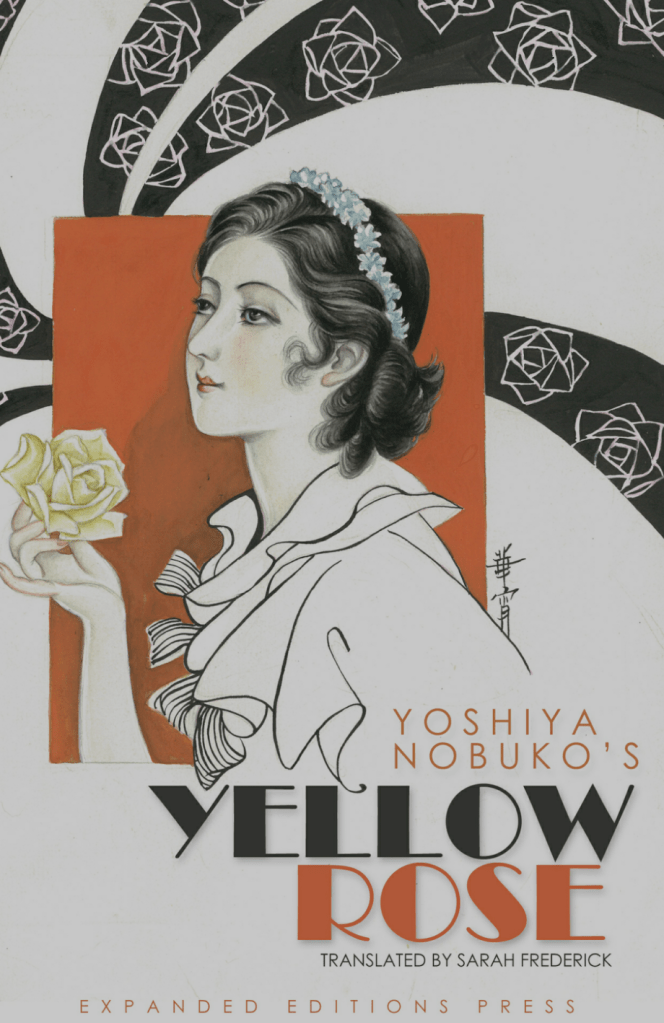

The second chapter, “Lesbian Bar Talk,” opens with the claim that “[i]n contrast to gay men, lesbians have been underrepresented in Japanese society,” and that “[n]ot only are the lives of lesbians in Japan invisible, but also research in queer studies excludes lesbianism for the most part.” Looking back at the landscape of Japanese literature, this statement certainly resonates. While there appears to be a growing presence of lesbian characters in contemporary Japanese fiction, they are still, for the most part, overlooked or marginalised. One of the few prominent Japanese lesbian authors I am aware of is Nobuko Yoshiya. To date, only one of her works—Yellow Rose, translated by Sarah Frederick—has been made available in English, and even then only in eBook format. (I have, in fact, considered getting a Kindle for this reason alone.)

To date, only one of her works—Yellow Rose, translated by Sarah Frederick—has been made available in English

In this section of the book, Abe turns her attention to lesbian communities in Japan, shifting the focus from the world of print to “lesbian bars in Shinjuku, Tokyo, at the turn of the century.” Despite this move from periodicals to physical spaces, her central concern remains the same—“the relationship between identity and language use” among queer individuals. Once again, Abe explores a unique communicative world, rich in subtlety and variation, and she does so in a style that is both engaging and accessible. The placement of this chapter immediately after the first is particularly effective, allowing readers to consider how modes of communication may differ—or resonate—across print and embodied spaces. In a sense, the advice columns discussed earlier appear as an abstract, distanced counterpart to the more immediate and intimate world of the lesbian bars examined here. Abe observes that “Japanese society offers so few spaces for otherness,” to the extent that both queer magazines and gay bars function as forms of refuge—sanctuaries where alternative identities can be expressed, shared, and affirmed.

The third chapter centres on “male sex workers dressed in female clothes” from “the late 1940s in the Ueno area.” Using this group as a case study, Abe examines the intricate relationship between language, gender identity, and sexuality. The clothing worn by these men may be interpreted in a manner analogous to the language they employ—both functioning as performative, mutable, and context-dependent modes of expression. Several of Abe’s insights into the conditional, complex, and nuanced nature of language could, indeed, be extended to clothing as well. This chapter also incorporates direct quotations from members of the community, revealing a diverse spectrum of feelings and perspectives regarding their identities, their work, and their experiences of femininity.

In the second half of the book, Abe delves more deeply into the intricate relationship between queerness, language, and our perception of reality. She explores the language used both by and in reference to prominent queer Japanese figures, including singer Miwa Akihiro and novelists Yukio Mishima and Edogawa Rampo. What constitutes passive, offensive, playful, or performative language emerges as something highly conditional—often fluid and context-dependent. Queer individuals in Japan, as Abe illustrates, develop their own distinctive strategies for navigating these shifting linguistic terrains.

The popular anime series Crayon Shin-chan

Even non-queer media in Japan engages in playful explorations of gender and language. In the popular anime series Crayon Shin-chan, there are “many episodes where Shin-chan plays with girls’ speech.” As a five-year-old, Shin-chan frequently mocks “the social norms children are being taught” and explores “the breadth of his world and all its possibilities, with no whiff of fear or discrimination.” These moments carry significant impact, precisely because they emerge from the innocent curiosity and boundary-testing of a child. Abe notes that both she and her son enjoy watching Crayon Shin-chan together—not only for the character’s playful subversion of norms, but also for his openness and imaginative embrace of difference.

In the final chapter, “Queen’s Speech as a Private Matter,” Abe shifts her focus to the more intimate, everyday use of language among queer individuals. This, she explains, “is an issue with both personal and political dimensions, one with which they must engage in everyday life.” For some, the way they refer to themselves—and the linguistic modes they adopt—can offer a release of tension, or even serve as “an escape.”

Abe concludes that queerness, as a term, “remains essentially undefined,” and her approach deliberately embraces the ambivalence and ambiguity inherent in that definition. While I remain somewhat uncertain about the notion of “language as a performative practice that produces reality,” it nonetheless offers a compelling and illuminating framework for understanding the complex, multifaceted nature of queer identity.

How to cite: McBride, Jane. Speaking in Queer Tongues: Language, Identity, and Everyday Resistance in Hideko Abe’s Queer Japanese.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 25 Mar. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/03/25/queer-japanese.

Jane McBride is a PhD student at the University of Galway in Ireland. Her research is on liminality in urban and digital contexts. Other topics of interest include East Asian literature, electronic and experimental music, digital humanities, comics, and Lewis Carroll. Jane is also a proofreader and artist. Her music and illustrations can be found online under the name Jane Eksie. [All contributions by Jane McBride.]