📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

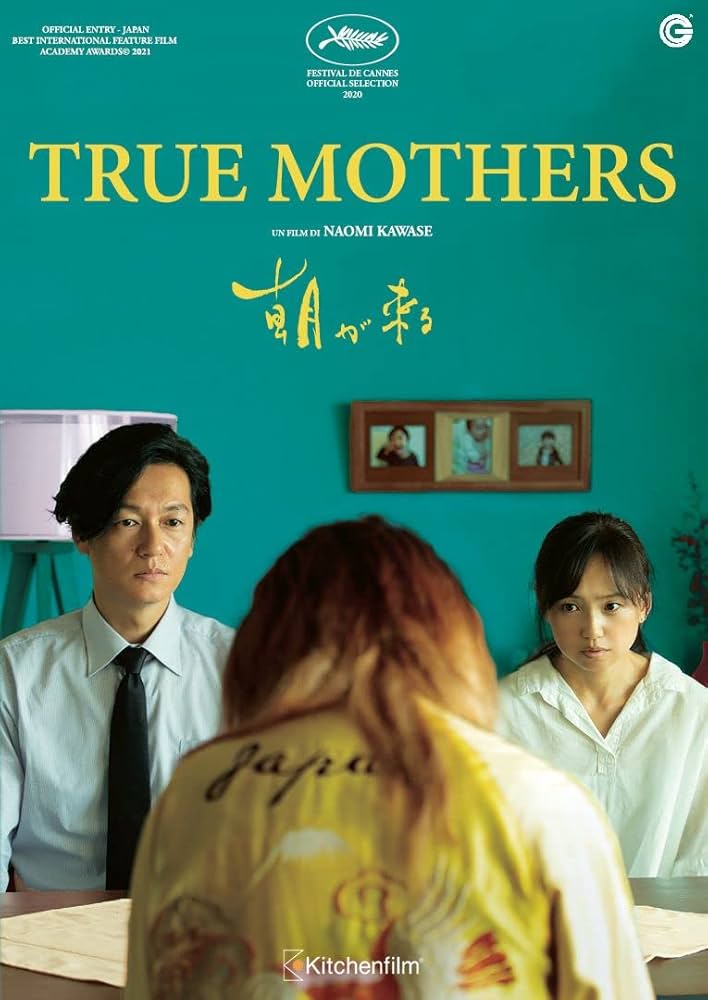

Naomi Kawase, True Mothers, 2020. 140 min.

Are human faces a resource? Are they a commodity? Can they be picked like grapes and harvested like grain? Can they be stored and sold on the market? Not only do Facebook and Instagram seem to confirm as much—so too has the entire film industry for over a century. Major film studios are, in essence, founded upon the production and consumption of faces. Producers and directors use them as raw material, the building blocks of cinema: “Look scared!” “Look happy!” “Look as though you are deeply in love!” Storylines are conceived, drama is orchestrated, and turning points are carefully crafted in a process that, step by step—face by face—moves towards the final, coveted product. In this sense, the filmmaker becomes a curator of faces and their expressions. He selects them, arranges them, and transforms them into a marketable, coveted collection: a radiant assemblage of dazzling smiles and evocative cries; a butterfly collection of laughter and tears—faces pinned to their expressions.

But it sometimes happens that a face in a film does not quite fit—that it appears, somehow, at odds with its scripted and predetermined function. For reasons that are precisely difficult to pinpoint, a role may suddenly be transgressed, a boundary unexpectedly crossed; a look or a glance may overflow the character and the plot, carrying us away—beyond the confines of the narration. In such moments, we cease to see merely a face—we begin to witness something else: a person emerging on the screen. We find ourselves, suddenly and unexpectedly, in the presence of a human being. This is a rare and magical transformation, one that does not often occur in cinema. Most directors do their utmost to prevent it: while a character is controllable and shaped according to the filmmaker’s intentions, a human being is not. A human being always exceeds what can be circumscribed or fixed within the frame of a film. Wherever the truly human emerges, stories grow uncertain, narratives begin to tremble, and a dimension of unknowability and unpredictability is born.

This is precisely what unfolds in Japanese director Naomi Kawase’s film True Mothers (2020). The narrative follows a fourteen-year-old schoolgirl, Hikari (portrayed by Aju Makita), who, after a brief but intense romance with a classmate, falls pregnant. Hikari’s parents, fearful of gossip and social disgrace, decide to send her away to a distant home for expectant teenage mothers, where she is to remain throughout her pregnancy and—once the child is born—relinquish the baby for adoption. The film, in this way, revolves around the significance of faces in more than one sense: not only is Hikari sent away in order to preserve the “face” of her parents, but she must pay for their good appearances by forfeiting her own. First, she is hidden from view during her pregnancy—then, once the baby is born, she is to become the unknown, faceless mother of the child. The entire story is thus shaped by a game of hide-and-seek with faces—faces absent where they were meant to be, and later, as the narrative unfolds, faces appearing in unexpected and dislocated places.

What is most striking in this film is not so much the story itself, but rather how a single face—the face of Hikari, that is, the face of Aju Makita—gradually grows beyond its filmic function. It is in the moments when the camera simply lingers on her, without editing, without movement, that a subtle transformation takes place. We see her standing still and expressionless by the sea. We see her in close-up, the wind gently stirring her hair—a breeze from the shore that she appears not to register. Nothing happens in these scenes: they propel no action, convey no overt emotion, and express no discernible psychological state. And yet these empty moments are, paradoxically, full—rich in another, more profound sense. Rather than capturing a character, the camera sets an individual free. Expressionless, Makita now serves nothing and no one—she owes nobody anything, not even the faintest suggestion of a smile. Her face is no longer turned towards the camera, towards the world, or towards communication, but instead returned to itself. In this sense, we are witnessing a deeply private moment: Makita is no longer performing—she simply is. She offers only her silent presence. Narrative momentum is suspended to offer the audience a rare and unexpected gift—to glimpse an individual freed from function, liberated from discourse, emancipated from all demands. It is only a moment, a brief rupture in the continuity of the story, but it is enough to shake its foundations. The plot resumes—but it is no longer quite the same. We have come too close to a human being to be satisfied with a mere character. Acting and expression return, as they inevitably must—but not without friction. For what, after all, is more vulnerable, more private, than the human face?

How to cite: Kølle, Anders. “The Face Of Integrity In Naomi Kawase´s True Mothers.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 24 Mar. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/03/24/true-mothers.

Anders Kølle is lecturer of Communication Arts at Khon Kaen University, Thailand. Holding a PhD in Media and Communications from The European Graduate School, he has taught art and philosophy at several universities, including the University of Copenhagen and Assumption University, Bangkok. His work focuses on contemporary encounters between philosophy and art, and on art’s potential to produce new modes of thinking and create new forms of critique. His publications include On Being Ridiculous (Delere Press, 2024), The Technological Sublime (Delere Press, 2018), and Beyond Reflection (Atropos Press, 2013). [All contributions by Anders Kølle.]