Japanese cinema has long been a vanguard of distinctive stylistic choices, particularly in the realm of horror. J-horror eschews gratuitous special effects in favour of an atmospheric approach that meticulously cultivates suspense, delivering an experience that is profoundly unsettling. Ringu (1998), Hideo Nakata’s directorial breakthrough, remains one of the most celebrated Japanese horror films, rekindling global fascination with the genre—an interest originally ignited by seminal works such as Onibaba (1964) and Kwaidan (1964). These stylistic sensibilities appear to have been inherent to Japanese horror from its inception. In 1926, at a time when horror cinema in the Western world was still in its nascent stages, Teinosuke Kinugasa created a transgressive masterpiece. A Page of Madness, Japan’s first silent horror film, drew inspiration from the work of Nobel laureate Yasunari Kawabata. The film chronicles the harrowing psychological descent of a man who, in a desperate bid to liberate his wife, takes on the guise of a janitor within a mental asylum. Its avant-garde visuals, saturated with disorienting imagery, render it a profoundly unnerving watch. The film exemplifies an expressionist sensibility, its psychological undertones serving as a testament to the depth of early Japanese horror. Decades later, as Hollywood’s horror landscape became inundated with formulaic slasher films, Ringu distinguished itself through its masterful evocation of atmospheric dread, offering a chilling narrative imbued with a uniquely Japanese sensibility. A closer examination reveals that its underlying themes echo the spectral folklore and eerie storytelling traditions that have permeated Japan’s cultural consciousness for centuries.

The art of storytelling is deeply rooted in nuanced ancient traditions that have endured for centuries. It is, therefore, only natural that macabre tales have constituted a significant part of oral history. One such tradition is Hyakumonogatari Kaidankai (百物語怪談会), which translates to “A Gathering of One Hundred Supernatural Tales.” This parlour game, imbued with Buddhist influences, was a popular pastime in Japan during the Edo period (1603–1868)—an era in which narrative storytelling flourished. The game’s premise was simple yet profoundly eerie: participants would take turns recounting one hundred ghost stories, extinguishing a candle after each tale. As the room was gradually plunged into darkness, an increasingly sinister ambience pervaded the gathering. It was through Hyakumonogatari Kaidankai that the lore surrounding yōkai1—supernatural creatures and spirits—proliferated during the Edo period. Folktales from across Japan were shared, either recounted from personal experience or passed down through generations. Many participants also fabricated their own ghost stories, further enriching the expanding tapestry of yōkai mythology. Ghost stories—kaidan—occupy an integral place in Japanese culture, traditionally told during the summer months. Their enduring presence is marked by the seasonal resurgence of horror cinema, television series, and paranormal broadcasts, all heralding the arrival of the season’s spectral storytelling.

“Night Parade of One Hundred Demons”, Japanese Visual Culture, accessed 24 March 2025.

Centuries before the emergence of the oral tradition of Hyakumonogatari Kaidankai, during the Heian period (794–1185), one of Japan’s most renowned literary works, The Tale of Genji, wove themes of the supernatural and inexplicable into its narratives. The Heian period was an era of remarkable cultural prosperity, during which storytelling became increasingly formalised and refined. Court nobles and the aristocracy patronised artists and performers who specialised in the recitation of poetry, folk tales, and epic sagas. It was within this flourishing literary milieu that seminal works—most notably Murasaki Shikibu’s The Tale of Genji—emerged, firmly establishing storytelling as a fundamental pillar of Japanese culture. As folklore assumed a more structured form, there arose a corresponding effort to codify and define supernatural phenomena through language. The term mono-no-ke, still in use today, came to signify enigmatic forces or spectral entities. Another enduring term, oni, gained prominence during the Heian period, referring broadly to terrifying or monstrous beings.2 Heian-era texts frequently evoke the concept of hyakkiyagyō—a spectral procession of ominous creatures weaving through the capital under the cover of night. The phrase, which translates roughly as “night parade of one hundred oni,” captures the era’s preoccupation with the otherworldly, a fascination that would continue to shape Japanese folklore for centuries to come.

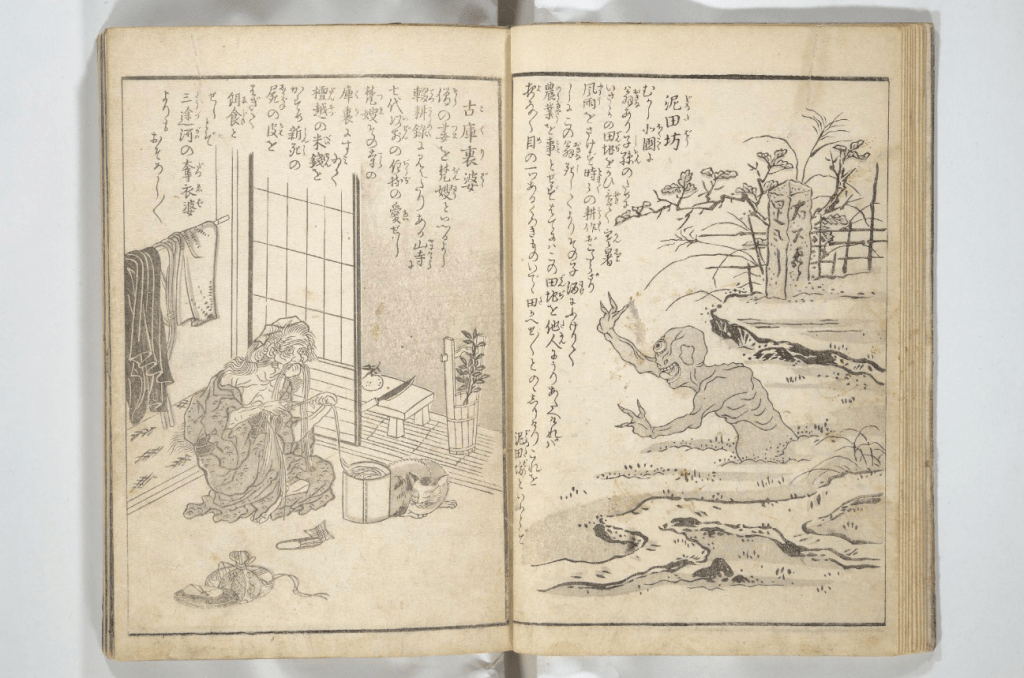

While literature explored the uncanny through works such as The Tale of Genji, the visual depiction of supernatural beings flourished during the Muromachi period (1336–1573), particularly through emaki scrolls. These illustrated scrolls—long, horizontal rolls of paper or silk—could be unfurled to reveal a sequential narrative, often accompanied by text. Emaki became a popular medium through which yōkai were vividly portrayed, allowing their imagery to permeate the wider populace and gain cultural traction. Not all yōkai were intended to evoke fear. The illustrated scroll Hyakkiyagyō Emaki, attributed to Tosa Mitsunobu, helped develop an artistic genre of its own—presenting colourful, often humorous variations of yōkai, replete with whimsical and exaggerated features. In examining the historical trajectory of storytelling—particularly in relation to yōkai—folklorists have paid considerable attention to the Edo period (1603–1868). This era marked a significant shift towards the intellectualisation and documentation of supernatural beings. The approach was encyclopaedic in nature, providing a more tangible foundation for the conceptualisation of these mysterious entities. Yōkai during this time featured not only in scholarly catalogues but also across popular media: in theatre, visual art, literature, and especially in the illustrated, manga-like booklets known as kibyōshi. These depictions often cast yōkai in a playful light, rendering them as sources of amusement rather than terror. One of the most prominent contributors to this visual tradition was the artist Toriyama Sekien (1712–1788), who produced a series of influential publications illustrating over two hundred distinct yōkai. His work seamlessly blended folklore with imaginative invention, setting the precedent for subsequent generations of artists and storytellers.

One Hundred Monsters Ancient and Modern (Hyakki shūi)

Toriyama Sekien produced illustrations of specific yōkai—some conjured entirely from his own imagination, others drawn from Japanese folklore and classical Chinese literature. Each page of his catalogue featured a delicate line drawing of a distinct supernatural being, often accompanied by a clever play on words. The result was an extraordinarily whimsical encyclopaedia—an imaginative compendium devoted to the rich and enigmatic world of the Japanese supernatural.

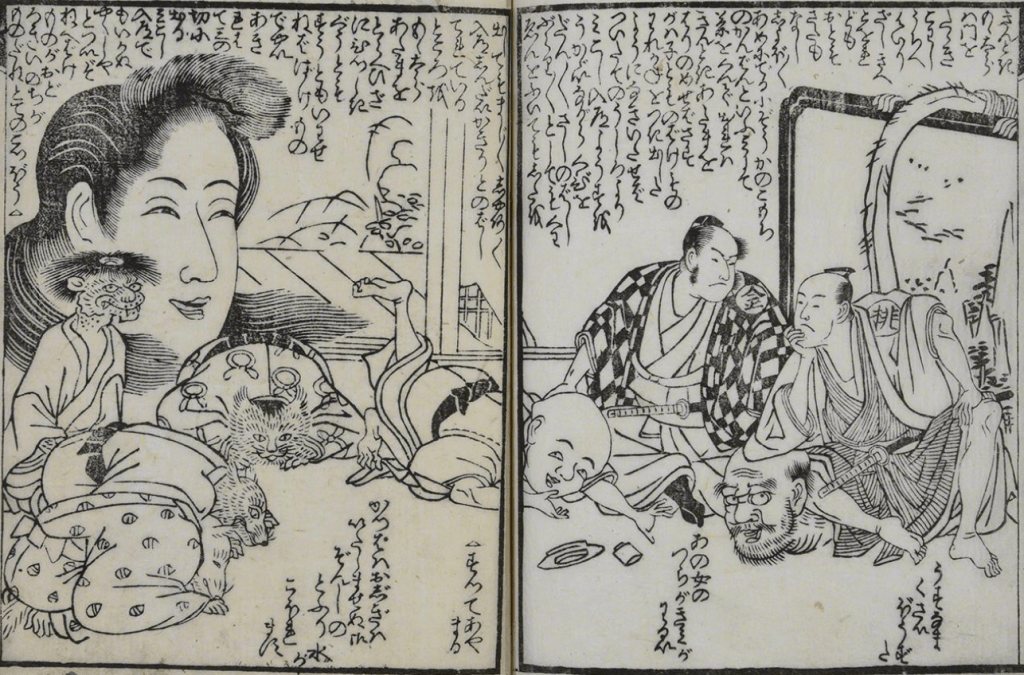

“Sannin Kodakara-bakashi (The Peach-Eating Treasure Trio) is a kusazōshi featuring two of Japan’s most famed folklore heroes, Momotaro and Kintarō, on an adventure. They visit an old temple and are attacked by bakemono, which they defeat.”(Courtesy Kagawa Masanobu)

The term “yōkai” gained widespread popularity during the Edo period; however, prior to its emergence, another word was frequently employed in prose, Kabuki theatre (a traditional form of Japanese performance) and misemono spectacle shows—lavish exhibitions and freak shows, often imbued with theatrical flair. This earlier term, bakemono—literally translating to “a changing thing” or “a thing that changes”—emphasised transformation, a trait commonly associated with many yōkai. Nonetheless, bakemono was used more broadly to describe an array of oddly shaped, fearsome, or aberrant entities, as well as phenomena capable of altering their form. In kusazōshi—a genre of illustrated literature akin to modern picture books or manga—the term bakemono appeared frequently, its reference to fantastical figures practically inevitable. Today, bakemono continues to be used informally in everyday conversation and, on occasion, in literary and academic contexts. The popularity of the term yōkai gained further momentum during the Meiji period (1868–1912), largely due to the influential philosopher and educator Inoue Enryō (1858–1919). A pioneering thinker in the reception of Western philosophy, Inoue played a crucial role in shaping modern Buddhist thought and disseminating imperial ideology during the latter half of the Meiji era. He became widely known for debunking myths and superstitions, and through his scholarly endeavours, helped popularise the use of the term yōkai as a catch-all category for the strange and mysterious. Later, the folklorist Yanagita Kunio adopted yōkai as a generic term in his academic writings during the early twentieth century. By the century’s end, yōkai had become a universal concept within the field of Japanese folklore studies. Yet, the greatest credit for the widespread dissemination and popular imagination of the term belongs to the celebrated manga artist Mizuki Shigeru (1922–2015). A household name within the world of Japanese comics, Mizuki is best known for his iconic series Gegege no Kitarō, in which yōkai—conceived as natural spirits—are brought vividly to life. Through his work, yōkai were reintroduced to contemporary audiences with charm, nuance and enduring cultural resonance.

Japan’s ancient folklore reveals an intrinsic relationship with the “paranormal”—a connection that has endured across millennia of literary and artistic expression. Where many cultures have consigned such phenomena to the realm of myth, Japan has rendered the supernatural tangible through its rich traditions of storytelling and visual representation. Japanese cinematic horror distinguishes itself from other global traditions by maintaining a profound link to these bygone eras—its narrative techniques deeply rooted in historical modes of expression. This cultural continuity continues to shape the ways in which fear is conceived, experienced and conveyed.

- yōkai (妖怪, “strange apparition”) are a class of supernatural entities and spirits in Japanese folklore. ↩︎

- The information has been drawn from Michael Dylan Foster’s work on yōkai. He outlines the emergence of Oni in his book, The Book of yōkai: Mysterious Creatures of Japanese Folklore. ↩︎

Some useful inks:

▚ A Brief History of Japanese Horror

▚ The Encyclopedia of Japanese Horror Films, edited by Salvador Jiménez Murguía

▚ Timeline of Japanese Cinema History: Pre-Cinema History

How to cite: Gogoi, Tushi. “Before J-Horror: The Paranormal in Ancient Japanese Writing.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 24 Mar. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/03/24/j-horror.

A writer with a passion for storytelling, Tushi Gogoi is currently experimenting with different genres of writing. Her primary interest lies in narrative fiction—with a particular fascination for the horror genre. She has engaged in multiple research projects, most notably her thesis, “The Study of the Influence of Folklore on the Evolution of Japanese Horror Films,” which has significantly shaped her understanding of folklore’s impact on storytelling. Through both research and creative writing, she continues to explore the depths of horror and its evolving narratives. [All contributions by Tushi Gogoi.]