📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

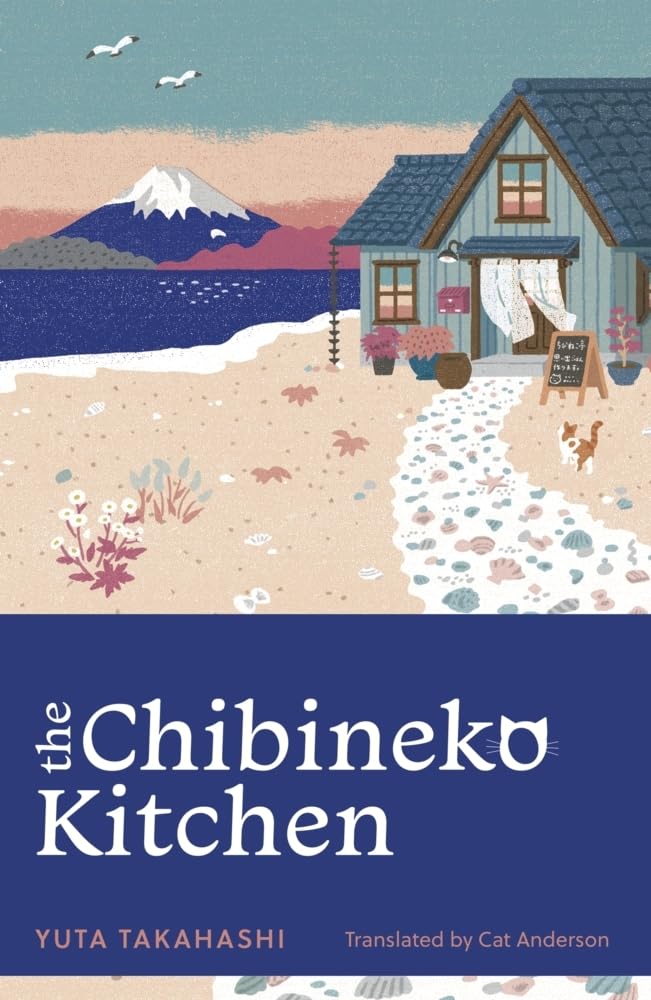

Yuta Takahashi (author), Cat Anderson (translator), The Chibineko Kitchen, John Murray, 2024. 192 pgs.

The Japanese iyashikei—or healing—genre has resonated deeply with readers worldwide, offering solace and comfort through its tender storytelling. Yuta Takahashi’s The Chibineko Kitchen is a poignant addition to this tradition. The first in a seven-book series set in the eponymous restaurant, it has been deftly translated from the Japanese by Cat Anderson.

As readers turn the pages of The Chibineko Kitchen, they are transported to the tranquil banks of the Koitogawa River. A white seashell path leads to a wooden building with blue walls, reminiscent of a cosy boathouse or beach hut. A modest chalkboard, bearing elegant yet unassuming lettering, greets visitors: “The Chibineko Kitchen. We serve remembrance meals.” There are no additional signboards or details about the menu—just a quiet footnote: “This restaurant has a cat.”

The setting itself is an invitation to escape the relentless bustle of daily life, seamlessly intertwining with the novel’s central premise—the opportunity to dine with the departed, to see them one final time. The Japanese term kagezen refers to remembrance meals served for the deceased, with the belief that their souls feed on the aroma of the food. Rumours swirl around The Chibineko Kitchen, whispering that here, one may meet lost loved ones once more. Kotoko, the novel’s protagonist, struggling to cope with the loss of her brother, arrives at the restaurant upon the recommendation of a friend.

Where there is love, there is grief. Bereavement does not fade—it merely shifts in intensity, lingering in the quiet spaces of everyday life. Those left behind grapple with endless negotiations of the self, haunted by what-ifs and the guilt of unspoken words. The desperation for one final moment of connection is profound. The novel’s characters—each carrying their own sorrow—are bound by this yearning. Kai, the restaurant’s owner, is no exception. Though he bears the weight of his own grief, he continues to serve kagezen to his guests. Taiji, another visitor, is plagued by the abrupt disappearance of his first love, oblivious to the truth that eludes him. The elderly couple, Yoshio and Setsu, embody an enduring love that transcends mortality. The departed themselves appear in a dreamlike state, lingering in the liminal space between life and death. And then, of course, there is the chibineko—the little cat—who comes and goes as it pleases, a silent guardian of this sacred place.

The novel unfolds through a delicate interplay of intertwined narratives, heartfelt conversations, and sumptuous meals—emotions and flavours wafting from the pages. Takahashi’s deep love for her home prefecture, Chiba, and her reverence for traditional Japanese cuisine imbue the story with a richness that transcends mere description.

Mortality is inescapable, and so too is the grief that accompanies it. The patrons of The Chibineko Kitchen seek not just an audience with the past but an escape from the gnawing uncertainty—were they responsible for their loved ones’ deaths? Did they do enough while they were alive? Could they have changed anything? The questions have no definitive answers. There is no immediate peace, no effortless solace. But is there hope? Is there a way to numb the suffering?

The Chibineko Kitchen is a meditation on acceptance and healing. Through Takahashi’s universally resonant themes, her characters inch towards closure. The novel is a tender, sentimental read—one that brings tears to the eyes even as it offers the comfort of a warm embrace. It flows with the quiet philosophy of wabi-sabi, much like the bittersweet beauty of falling cherry blossoms—a kagezen for the soul, indeed.

How to cite: Yadav, Aditi. “Dining with the Departed: Yuta Takahashi’s The Chibineko Kitchen.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 2 Mar. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/03/02/kitchen.

Aditi Yadav is an amateur writer and translator from India. She is also a South Asia Speaks fellow (2023). Her works can be found in, among other places, Rain Taxi, The Punch Magazine, Usawa Literary Review, Gulmohur Quarterly, Borderless Journal, and the Remnant Archive. [All contributions by Aditi Yadav.]