📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

in.light.of.living—Sik.Faan (author), jck (illustrator), and daanngaazai (calligrapher), Pattern, Language, Setting—A Glossary of City Spaces in Hong Kong, Enlighten & Fish, 2021. 240 pgs.

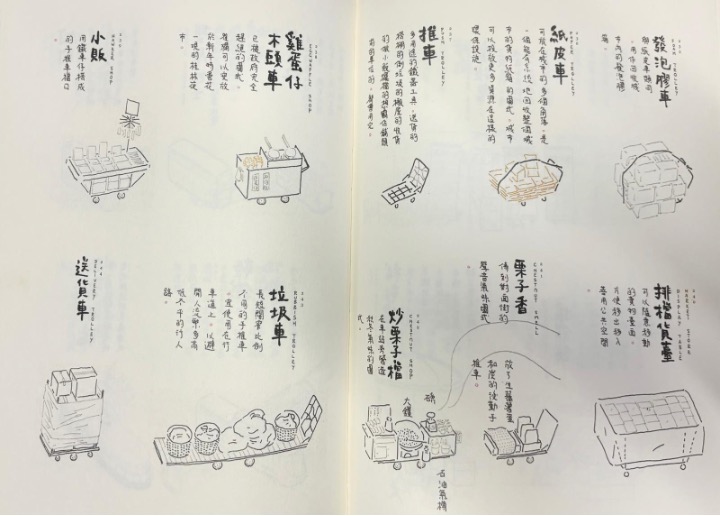

Pattern, Language, Setting—A Glossary of City Spaces in Hong Kong is an interdisciplinary attempt to observe patterns weaving the city’s fabric by the collective in.light.of.living—three anonymous creatives. The book shares similarities with an academic publication, consisting of an introduction, methodology, and findings. Disguised within this structure is a light and engaging bilingual read. Bridging the two versions are over 20 thematic photographic evidences, indexes, and a spatial glossary. The glossary functions much like a picture dictionary, containing 453 sets of hand sketches and calligraphy. Each item is assigned an arbitrary identification number, yet items, types of people, and activities of similar nature or relevance are listed together.

The spatial glossary.

The contributors make a concerted effort to collect fragments and identify puzzle pieces of the quotidian—elements whose significance in shaping Hong Kong’s way of life (up to 2021) has either been neglected or taken for granted. They also subtly challenge conventional notions of chaos and order in built, natural, and hybrid spaces. Sik.Faan, the leading author, underscores that Hong Kong is a unique city where vernacular architecture—informal structures and spaces created by individuals without formal architectural training—plays a crucial role. Such architecture enables residents to adapt, modify, and improve their cultural habitation, countering what the author terms the “predictory framework of the modern city.” This concept refers to imported architectural designs, materials, and regulations that fail to accommodate the everyday needs of Hong Kong’s inhabitants. The mediator in this interaction is what Sik.Faan coins as the “interobject”—a novel concept defining vernacular architecture that appears to embody a degree of autonomy and resistance from people who, though not consciously aware of it, create such structures out of necessity:

Interobject is a product of neither modern nor traditional architecture. It is a series of architectural practices conceived by the different communities inhabiting the city in order to find a place for their desired cultural habitation. […] Interobjects in Hong Kong do not stand independently of their surroundings in terms of construction, ownership, and operation.

Entries 324 to 338 are about different types of gates and fences and their extended uses.

Although the author’s effort to deconstruct the city’s settings is commendable, the omission of all commonly used names in Hong Kong and their Jyutping pronunciations is a notable oversight. The author states that “a translated name in English is important for non-Chinese-speaking readers to get a sense of the culture behind the pattern”, yet inconsistencies arise in the book’s handling of translations. Entry 238 refers to a particular type of mobile food business, 雞蛋仔木頭車 (gai1 daan6 zai2 muk6 tau4 ce1, “gai1 daan6 zai/bubble waffle wooden trolley”), which is translated as “egg waffle shop”. This English translation fails to convey two crucial aspects: the itinerant nature of the business and the materials used to construct the trolley, both of which contribute significantly to its spatial identity.

Translation is a double-edged sword—it breaks down barriers, enabling greater accessibility to minority cultures, yet it can simultaneously introduce distance, making it harder for first-language and heritage speakers to associate with their cultural roots. Existing translations of gai daan zai include “Hong Kong-style egg waffle”, “bubble waffle”, and “Hong Kong egg cakes”, but none encapsulate the affectionate connotation embedded in zai2 (“son”), a diminutive widely used in the Hong Kong dialect. Meanwhile, entry 245 refers to the Hong Kong tramway as 叮叮 (ding1 ding1), using ding ding as the English name instead of 電車 (din1 ce1) or the expected “tram.”

A crucial opportunity to institutionalise references to Hong Kong-specific spatial patterns and cultural phenomena for a global audience—many of whom lack fundamental socio-cultural and geopolitical awareness of the city—has been missed. The translations within the book become a misdirected effort at Anglicisation, diminishing the unique characteristics that distinguish Hong Kong’s urban landscape from similar observations around the world. Last winter, bubble waffles were featured alongside German mulled wine and Bratwurst at Glasgow’s German Christmas Market. Of course, they can be enjoyed on any occasion and by anyone. But imagine if they were labelled gai1 daan6 zai2 instead—suddenly, they would feel out of place.

Despite this shortcoming, the book is beautifully curated and exemplifies the collective’s courage in capturing the elusive spirit of Hong Kong’s spatial identity. It evokes personal nostalgia—reminding me of a childhood game I played with my mother, carefully avoiding trench cover plates 整路地板 (zing2 lou6 dei6 baan2), translated in the book as “fix-road flooring” (entry 082). More than just an observational study, this book serves as a poignant reflection on nomenclature—a vital, untapped cultural asset for the diasporic communities of Hong Kong heritage. It provides a means to construct a new linguistic framework, preserve cultural identity, and pass it on, while simultaneously safeguarding against cultural appropriation.

Entries 235 to 244 are about different types of DIY trolleys and their purposes.

Entries 245 to 253 are about public transportation.

How to cite: Yeung, Vanessa Winghei. “The Importance of Nomenclature in Pattern, Language, Setting—A Glossary of City Spaces in Hong Kong.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 14 Feb. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/02/14/city-spaces.

Vanessa Winghei Yeung is a multilingual arts and heritage professional. Having lived in Hong Kong and Rome, she is now working to make Glasgow her home. Her writing has recently been featured on the website of the International Council of Museums (ICOM) and in the Scottish Book Trust’s Book Week Scotland Teaching Toolkit. Her short story, Victoria Harbour, was performed at the Liars’ League Hong Kong. Currently, she dedicates her efforts to writing about and researching decorative arts and modern architecture in pre-war Hong Kong. Her first academic article, exploring a fascinating yet short-lived interior decoration and furniture company, Arts and Crafts, Limited, is under peer review with the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch. In anticipation of the centenary of Art Deco in 2025, she is collaborating with a professor on a book celebrating Hong Kong’s Art Deco heritage. Follow her documentation and research journey: @artdecohongkong. [Read all contributions by Vanessa Winghei Yeung.]