📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

Click HERE to read all entries in Cha on A Woman Burnt.

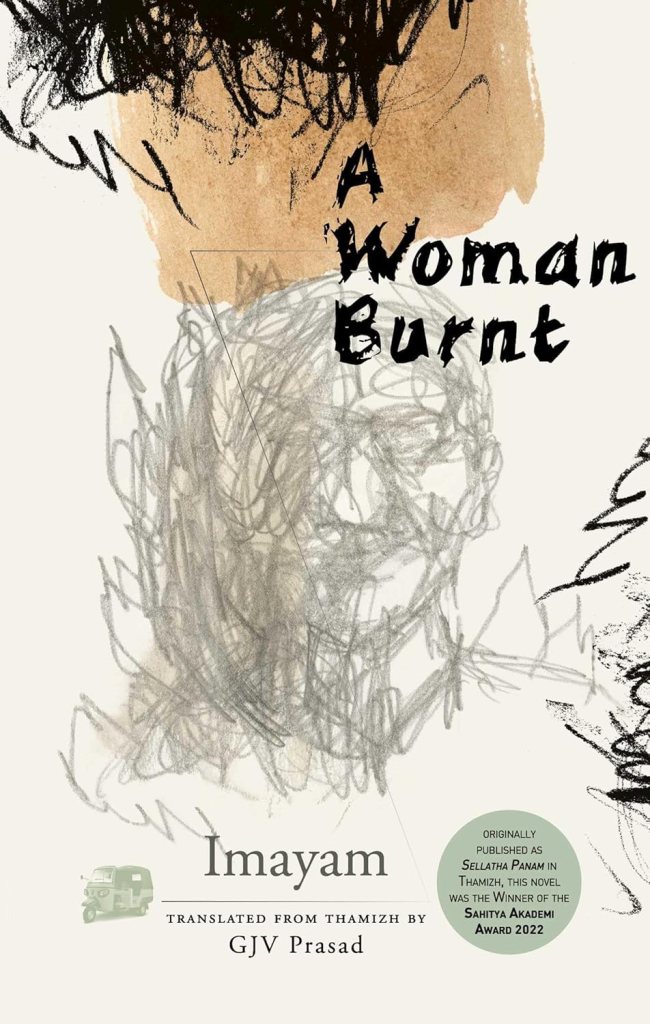

Imayam (author), GJV Prasad (translator), A Woman Burnt, Simon and Schuster India, 2023. 336 pgs.

We step into a new world—otherwise inaccessible—every time we read a translated work. In recent years, Indian literature has witnessed a remarkable shift, with several translated works gaining critical acclaim both in India and abroad. This has helped bridge the inevitable divide between regional and national literature, as Indian literature produced solely in English cannot fully represent a nation as diverse as India. However, Imayam’s novel A Woman Burnt does not confine itself to a specific cultural milieu. Though originally written in Tamil, its themes transcend regional identity. The novel probes the repercussions of enduring an abusive marriage and the societal norms that perpetuate it. In a country where marriage unites families rather than individuals, leaving an abusive partner remains deeply stigmatised. Moreover, marriage often serves as a tool to enhance social and financial standing, and various forms of marital abuse persist. This is not merely a Tamil concern—it is an Indian one.

Imayam’s A Woman Burnt presents the story of an obstinate Revathi, who—despite her education and social standing—marries an auto driver against her parents’ wishes. Her husband, Ravi, manipulates her emotionally, drawing her into his orbit until she becomes obsessed with him. As expected, her family vehemently opposes the match, yet Revathi not only chooses to marry Ravi but also remains with him despite his escalating violence. They have two children, and the family struggles with an impoverished existence. The stark depiction of poverty and domestic violence is harrowing, yet Revathi chose this life for herself.

At first glance, the novel may seem like yet another story of marital violence, but the issues it examines run far deeper. In a country where social class dictates the trajectory of marriages, such an outcome is unsurprising. The chasm between India’s rich and poor remains vast, with social class serving as a decisive factor in arranged marriages. Revathi’s family is educated and well-established—her father, Natesan, is a school headmaster, and her brother, Murugan, is a software engineer in Chennai. Revathi herself holds an engineering degree, yet instead of pursuing a career, she chooses to stay at home and marry a man of significantly lower social and economic status. Even more striking is her willingness to endure relentless abuse despite legal protections available to her.

The novel’s strength lies in its meticulous attention to detail, particularly in its depiction of Revathi’s stay in the hospital. Every action—every sip of tea, every hushed phone conversation—is rendered with striking precision. At times, these details verge on monotony, yet they provide an unflinching look at the workings of India’s public institutions. Revathi’s family carries cash, anticipating the need to bribe police officers—an implicit understanding of the systemic corruption that governs everyday life.

Revathi is a passive character throughout the novel, even as the narrative centres on her suffering. From the moment of her self-immolation to her final days in hospital, her story unfolds with painstaking intricacy. The novel does not shy away from exposing the bureaucratic hurdles in such cases—emergency admissions, legal entanglements, bribery, and society’s general apathy towards domestic violence. Each moment elicits sympathy for Revathi, yet it is impossible to overlook that she actively chose this path. She had the option to leave her abusive marriage but stayed, ultimately sealing her fate. Although India’s legal system offers protections for women in her situation, these safeguards are often out of reach for those who need them most.

The novel raises pressing questions about accessibility to justice. It also explores the ethical dilemma of intervention—should Revathi’s parents have taken legal action against her husband, even without her consent? There are no easy answers, and the novel does not provide them. A Woman Burnt is neither wholly domestic nor overtly political—it instead compels readers to grapple with the complex realities of human behaviour.

GJV Prasad’s translation reads seamlessly. Prasad, who taught literature at Jawaharlal Nehru University for decades before retiring in 2020, deserves recognition—translators are often overshadowed despite their critical role. Translation is not merely an act of reproduction; it is an act of creation. Without Prasad’s rendering, many readers would never have encountered Revathi’s harrowing yet necessary story. In a country as linguistically diverse as India, translation remains an essential bridge to understanding and appreciating its myriad voices.

How to cite: M, Fathima. “A Tale of Love and Abuse: Imayam’s A Woman Burnt.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 13 Feb. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/02/13/woman-burnt.

Fathima M teaches English literature in a women’s college in Bangalore, India. She likes hoarding books and visiting empty parks. [Read all contributions by Fathima M.]