📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

Click HERE to read all entries in Cha on Yiyun Li.

Yiyun Li, Must I Go, Penguin Random House, 2020. 368 pgs.

Lately, I find fewer and fewer books that surprise me—novels capable of gripping me from beginning to end, refusing to let go until the final page. Perhaps my patience has waned; perhaps I make poor choices; or perhaps every story has already been told, variations of familiar narratives reworked in infinite loops. And yet, every so often, when I least expect it, a novel appears that disproves my cynicism, reminding me that originality persists—that there are still voices capable of breaking through the noise.

My most recent surprise was Yiyun Li’s novel, The Goose Book. Until then, I knew nothing of her, so I turned to the internet. What I found was a writer marked by deep personal suffering—wounds she has transmuted into literature. That first encounter led me to Must I Go—and I must confess, Yiyun Li has now entered the ranks of my literary favourites.

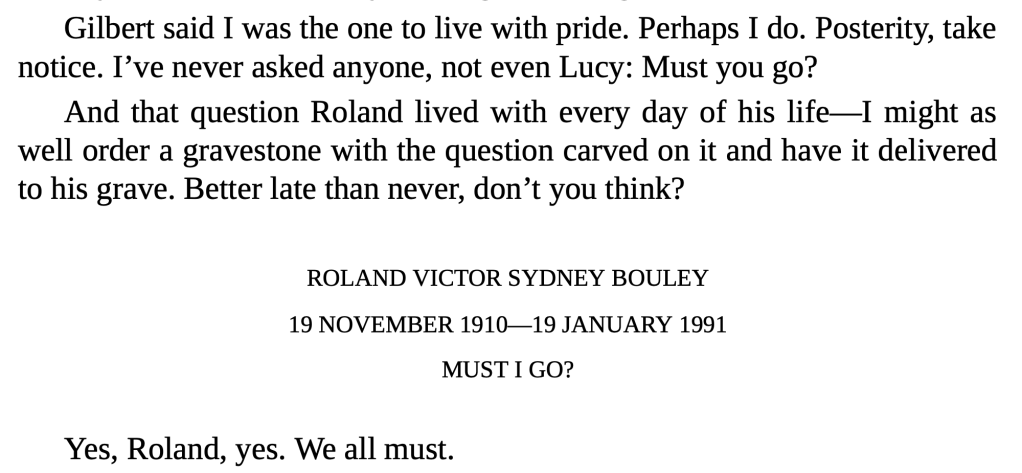

Readers familiar with Li’s work will know that she frequently returns to a singular obsession: the relationship between the living and the departed. Must I Go is no exception. The novel centres on Lilia Liska, an 81-year-old woman in 2010, who revisits her past while annotating the diary of her former lover, Roland Bouley—a man long dead.

Bouley was not a great love—neither a brilliant mind nor an object of exceptional beauty. And yet, Lilia reconstructs his presence through memory and his own words. Why? She is no sentimentalist, after all—a woman of quick wit and sharper cynicism, with little patience for fools. And yet, Bouley remains significant because of one thing: their brief encounter produced a daughter, Lucy, a daughter who later took her own life. In revisiting Bouley’s diary, Lilia embarks on an emotional excavation—tracing, however futilely, a path that might explain the inexplicable.

A skeletal summary makes the novel sound unremarkable, but Li’s craft ensures otherwise. Lilia is a masterfully drawn character, her voice shaping the novel’s rhythm and texture. Her irony acts as a buffer against the weight of grief, offering readers a wry, almost mischievous guide through an otherwise tragic terrain.

Structurally, the novel is unconventional. The first two sections follow Lilia in the third person, shifting between past and present. The third, however, is Roland’s diary—meticulously interspersed with Lilia’s sardonic annotations, addressed to her granddaughter Katherine. This layering of text within text lends the novel a fragmented, epistolary quality, though it is more accurately a collage—a mosaic of recollections, asides, and minute details that together construct a remarkable literary artefact. Against this backdrop, history seeps in—glimpses of the Gold Rush, the Great Depression, World War II, the 1945 San Francisco Conference that birthed the United Nations. The novel is not historical fiction, yet history is its scaffolding.

Given Yiyun Li’s biography, Must I Go inevitably invites autobiographical readings. Li has written candidly about personal tragedy—most notably, the suicide of her 16-year-old son, a grief she explored in Where Reasons End. That novel imagined a posthumous conversation between a mother and her lost child, an attempt to bridge the unbridgeable. In Must I Go, the same spectral presence lingers—Lucy’s suicide, another unanswered question, another mother left to make sense of the void. Some critics have argued that Must I Go functions as an extension of Where Reasons End—that Bouley’s diary is mere scaffolding for a meditation on maternal grief. If so, it is a novel disguised within a novel—a Russian doll of concealed anguish.

Yet, for all its tragic undercurrents, Must I Go is not a sorrowful book. Li resists sentimentality, allowing Lilia’s pragmatism to undercut any self-pity. Instead of despair, the novel raises sharp existential questions—about suicide, free will, regret, and the inevitable finality of life. Does it matter when we leave? Does it matter how? Lilia, ever unsentimental, offers her own answer in the closing pages:

A fitting epitaph—for Roland, for Lucy, and for all of us.

How to cite: Tataran, Dorina. “A Meditation on Memory and Loss: Yiyun Li’s Must I Go.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 12 Feb. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/02/12/must-i-go.

Dorina Tataran is from Bucharest, Romania. After being a journalist for several years, she has returned to her first love: books. She has been translating books from English into Romanian for over ten years now and from Asian literature she translated Weina Dal Randel’s The Empress of Bright Moon. She is also one of the editors of the online cultural magazine Semnebune.ro. She has published a few short stories in a local magazine and some excerpts from a novel-in-progress in a few others. She is passionate about Asian culture in general, and she is currently learning Korean and discovering more about South Korean culture, especially its literature and films. Dorina loves jazz, coffee and she thinks there is nothing more exciting than being a spectator of this ever-changing world, especially through its stories. [All contributions by Dorina Tataran.]