📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

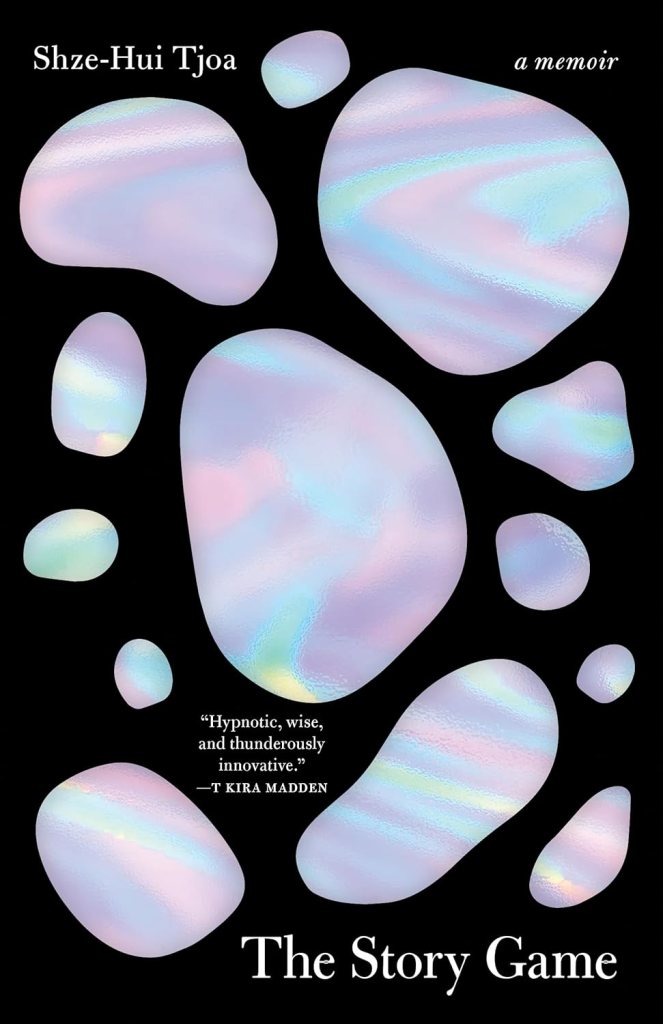

Shze-Hui Tjoa, The Story Game: A Memoir by Shze-Hui Tjoa, Tin House Books, 2024. 208 pgs.

It was exam season, except this time I was in university. This class was a bit less intense than others, and my professor was friendly. The allure of tangential tasks and thoughts was especially strong. I decided to listen to it and write my professor a long email, confessing I simply couldn’t keep “studying” while asking myself: what was the point of it all? If I could look at the Meiji period this way and that (the class was on the history of modern Japan), argue this and that about it, what was it for? What would it amount to? Besides, aren’t we where we are because of all that we’ve been through? Why argue about the nature of our past, if it was “good” or “bad” or led to this and that?

My professor replied with an equally long email, and some of those words I remember until today. He liked what I said about where we are and where we’ve been. If that were true, he said, doesn’t that mean that, if we can change the way we look at our past, we can also change the way we look at ourselves?

I was struck. That does sound wonderful, Professor. If only it were so simple. Memory is a funny thing.

In Excavation and Memory{pdf}, Walter Benjamin characterises memory less as an instrument for accessing the past and more as the medium. Tools and instruments have specific functions, an intention, a job, and an outcome in mind. On the other hand, memory is the medium in which our past is buried. Using the metaphor of archaeology, it is the earth. And digging—remembering, experiencing the past—is hard work. Perhaps more important than the recovery of fragments is noting where they were found, and how, by whom, and when. Digging can take a while, even at one site (see also: digging for underground MRT stations in Singapore). “In the same way a good archaeological report not only informs us about the strata from which its findings originate, [it] also gives an account of the strata which first had to be broken through.” Benjamin’s characterisation of memory is especially useful when considering trauma, which can heavily affect our abilities not just to change how we see our past but to see or discern it in the first place.

The Story Game involves a lot of looking, remembering, digging, and telling stories about all of it. It is set in a place called Room, with the narrator Hui talking to Nin, who she calls her younger sister. This is uncanny, as Benjamin also talks about a room or “Gemach” in his essay originally written in German. The fragments a digger recovers after returning over and over again to the same site “reside as treasures in the sober rooms of our later insights.” I get the picture of people in a large room, tired from their dig. As they look around and compare notes, their eyebrows spring up, they frown in thought, they nod. So that’s what remembering is like? You do the work first, look back on both the findings and the process, and understand later? Nin and Hui sort of do this, after every story/essay, back in Room.

When Shze-Hui began writing The Story Game, she thought she was writing a series of essays on politics, the politics of tourism, for example. This is the uppermost strata of the earth of the writer’s memory; what is plain to see for all, and what Hui presents to Nin when Nin asks for a story. This strata alone is wonderfully insightful. It touches on many topics. The book opens with a trip to Bali, with a devastating narration of a puputan and a page of references to boot. It is smart like that, intellectual, given its beginnings as a kind of sharp cultural commentary. Through these essays, Shze-Hui discusses the legacies of imperialism, the perils of greenwashing (including to yourself), being in Jerusalem, achievement in elite society, marriage, race, language, even the sad Tumblr girl trope. She is able to identify the dynamics of power and prejudice not just in these issues, but in how they intersect with and manifest in her personal life, with all its subjectivity. Her trip to Bali, for example, is pregnant with meaning given she is someone whose ancestors had fled Sumatra, their once-homeland. One reviewer wrote that this book tackles many complex themes, each fully realised (Ryan Walker/ryan.wrote.it), and I agree. I once read a book that tries to do something similar in the context of Singapore, but felt like I was implicitly being told what to think, even via fiction. This book has none of that.

This author’s views on society are always intertwined with her personal life, which she so willingly shares, even when unsavoury. And that is what she is really interested in: Lapping beyond essay and reaching the shores of memoir, The Story Game is life, remembered, presented, clarified, and re-presented. “So clever, I’ve heard countless people say to Thomas… How come you know how to cook with this kind of chilli!” I can hear the auntie’s voice in the essay discussing her marriage. Thomas is Shze-Hui’s white guy husband. Shze-Hui writes, “Through Thomas, people seem to imply, I have gained a free pass to a more rarefied domain. So of course, I am lucky; and of course, I should be grateful. But no one ever applies these same words to my white European husband. They use clever.” When it comes to these details, the author seems to be doing what Benjamin says we must be unafraid to do: to scatter the earth and turn it over as one turns soil. She notices the fine grains of the earth being dug, an act Benjamin calls the “probing of the spade in the dark loam.” I enjoyed watching Shze-Hui rub the earth between her fingers as the grains dislodge, fall, and become clearer on the page.

Following each story or essay, readers are drawn back to Room, where Nin and Hui engage in a reflective dialogue about the preceding narrative. This back and forth between Room and the ventures into wherever the story/essay goes gives the book a distinctly theatrical quality. It feels akin to a scene change, with a lights-out transition or a brief curtain closure. The book’s momentum is largely driven by these Room dialogues between Hui and Nin, and also by the lack thereof. As we transition from one essay to another—venturing out of Room and returning again—it feels as though we are delving deeper and deeper into the layers of the earth. With each descent, Nin’s interjections and critiques become increasingly sparse. Nin, who initially cajoles and challenges Hui, stiffens into a profound silence just before the book’s most revelatory essay, “The Story of Body.” Here is where we feel the work of digging through memory. We feel the tension as we witness “the attempt to look, not for something that one expects to find, but for what is unknown, surprising, and even troubling.” (Simine, S.Ad) Soon, Hui/Shze-Hui ends up turning her keen eye towards herself. The astute, incisive commentary turns into “astonishingly pitch-perfect” prose, an unravelling record of her confrontation with herself (Michele on Goodreads). In this climactic essay, Shze-Hui captures the raw, visceral essence of an enduring pain. In the synopsis, this journey is characterised as complex post-traumatic stress disorder (c-PTSD).

All of this is conveyed without the experimental layouts often found in creative non-fiction—no verses, no slashes breaking lines, no colons to signify speakers, no stage directions enclosed in brackets. Instead, the writing relies on paragraphing and indentation. These are essays, and I found their form both elegant and refreshing. The author employs italics with care, a point she addresses in her note on their usage, which I read first. She reflects on the role of italics in the act of othering on the page and explains her thoughtful choices, particularly given the book’s multilingual nature. For me, this approach was highly effective. The Story Game renewed my confidence in good ol’ blocks of text.

I found this dig harrowing. Yet, after finishing the book, I was left wondering: which is worse—awakening as she did, or suffering in silence and continuing life unaware? It was difficult to bear witness, but even harder to turn away. The book is beautifully written, and you don’t immediately grasp the magnitude of the author’s achievement because it feels so natural, so intuitive—much like the process of getting to know oneself. “Prompted, iterative honesty” captures it perfectly (Claire Chee via Electric Literature). Walter Benjamin once wrote that “genuine memory…[yields] an image of the person who remembers.” The portrait I have of Shze-Hui is of someone scuffed up as she emerges from the depths of her adventures, fitting right in with the tired diggers of Benjamin’s room. Like another reader who managed to meet Shze-Hui in person, I wanted to hug her, and I did.

As an author, I’d like to become someone who’s good at sitting with gross emotions – who can feel difficult feelings or make mistakes and grow in public ways, and so free others to do the same. I feel like that’s one of services that a good memoirist provides for their readers, actually.

—The author on her blog on 30 April 2023.

Yes ma’am, you have succeeded.

How to cite: Nur Hadziqah. “Excavation and Memory in The Story Game: A Memoir by Shze-Hui Tjoa.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 3 Feb. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/02/03/story-game.

Nur Hadziqah is a mother of one raised and based in Singapore. Other than literature, Hadziqah is interested in history, visual culture, Islam, and all of them put together.