📁RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

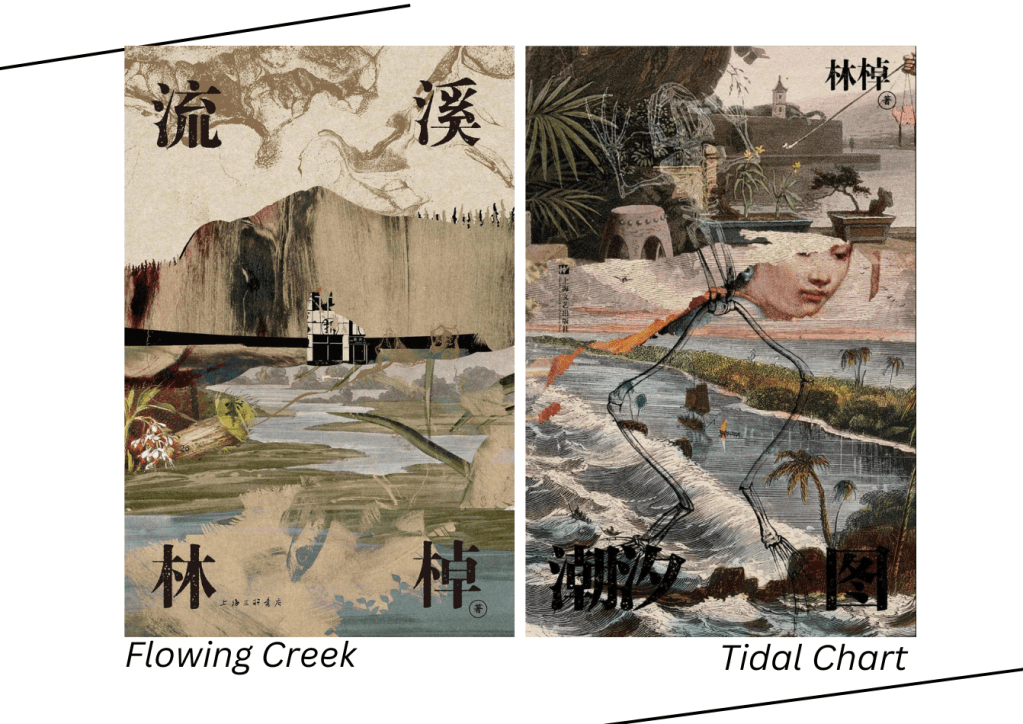

▚ Lin Zhao, Flowing Creek 流溪 (originally published in Mandarin Chinese), Shanghai Sanlian Publishing Company, 2020, 192 pgs.

▚ Lin Zhao, Tidal Chart 潮夕圖 (originally published in Mandarin Chinese with a variety of southern Chinese dialects), Shanghai Sanlian Publishing Company, 2022. 292 pgs.

Lin Zhao is an enigma.

There are few adjectives in the English language that can adequately encapsulate this emerging supernova of contemporary Sinophone literature. Shenzhen native Lin Zhao 林棹 is celebrated for her imagination and writing style. Through her exploration of feminism, language, and post-colonialism, her Flowing Creek (流溪) and Tidal Chart (潮夕圖) intricately weave forgotten narratives of Southern China into a rich tapestry of historical memory and mythical storytelling. Lin reclaims the voices of the marginalised, offering an evocative portrayal of lives and experiences often erased or overshadowed by dominant cultural narratives. Her words echo the elegance of Eileen Chang, while her prose flows with the introspective fluidity of Virginia Woolf. Blending the beauty of traditional Chinese literary aesthetics with the stream-of-consciousness techniques rooted in Western literary traditions, Lin’s oeuvre becomes a destination where milky, feral dreams evoke the landscapes of Southeast China in all their haunting splendour.

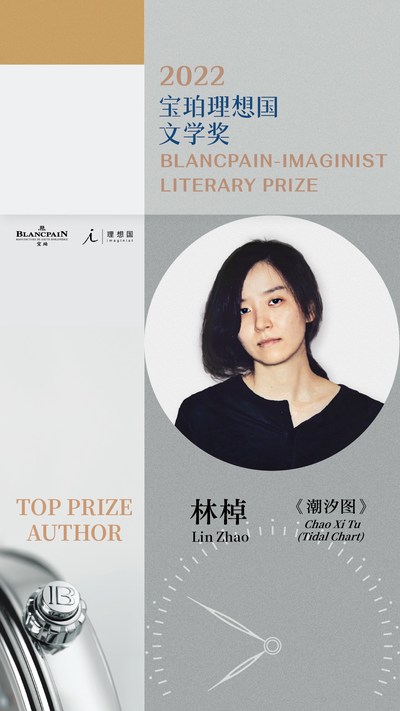

Compared to the broad, fertile plains that nurtured the central heartland of Han Chinese culture, Southern China—particularly Guangdong and Fujian—has historically been a refuge for dissidents and the exiled. Often dismissed as a humid tropical jungle, it has long been associated with destitution and lawlessness. With Flowing Creek (2017) and Tidal Chart (2021), Lin has risen to literary stardom within just a few years. She has consecutively won major literary awards in China, including the Blancpain-Imaginist Literary Prize and the Shi Nai’an Literary Award. There are only a few examples in the history of contemporary Chinese literature of southern female writers demonstrating an impressive command of the Chinese language—the most notable being Eileen Chang.

After graduating from Southwest Minzu University in Chinese studies, Lin’s life had very little to do with being a professional writer in the first decade of her adulthood, not until she pulled out the manuscript of Flowing Creek by the time she hit her mid-thirties. “I have read Lolita no less than twenty times before writing Flowing Creek”, said Lin in an interview. She understood the mission of being a writer vicariously through Nabokov’s canon. While beautifully written, Lolita tells the story of Humbert Humbert, a morally corrupted and narcissistic paedophile as he preyed on his teenage stepdaughter, Dolores Haze, as he preys on his teenage stepdaughter, Dolores Haze, ultimately leading to his own moral and personal degeneration. Referencing French and Greko-Roman mythology in this pioneeringly modern fiction, Nabokov provoked the world with his hauntingly mesmerising words.

Heavily inspired by this controversial book, Lin’s debut, Flowing Creek, centres on a fallen middle-class Chinese girl. Zao’er, a stereotypical single daughter born and raised at the peak of the One Child Policy in a traditional southern Chinese family that values sons, grows up sensitive, reserved, and grappling with low self-esteem. She struggles with inadequacy in every aspect of her life—academics, relationships, and her fractured family. Zao’er’s father, succumbing to familial pressure and personal choice, abandons the family when she is young. He remarries a woman whom Zao’er disdainfully calls “the woman with yellow hair.” Zao’er is deeply aware of her position as the unwanted daughter in the household, as she witnesses the crumbling of her mother’s marriage and struggle to preserve dignity among other relatives. This permeates through her teenage years when she meets Baima, an estranged yet charming young man with whom she develops a tumultuous romantic connection. This dangerous yet intense relationship marks her first love and opens up Pandora’s box, which gradually leads Zao’er onto a downward spiral. Lin’s creation of an unreliable narrator (similar to Nabokov’s Humbert) is convincing and enthralling, engaging readers in her intricate literary techniques.

The phenomenal success of Flowing Creek, a debut by an unknown author, rapidly elevated Lin to literary prominence, achieving national bestseller status across multiple platforms.

The book resonates deeply with the struggles of highly educated Chinese women raised as single daughters during China’s era of unprecedented economic growth. Lin’s literary inspiration challenges the stereotypical Western imagination of China—as an authoritarian, late-capitalist urban jungle threatening the global order, or as an ancient civilisation deemed politically impenetrable and culturally irrelevant. Lin is a shrewd observer; by telling the story of an unreliable narrator, she pays homage to those whose emotions were habitually dismissed. “Childhood is a room of yours… wherever we go, we are simply circling in this room”. Flowing Creek evokes a transcendent experience, akin to basking in the golden warmth of late summer at the age of fourteen.

As one of the first economic zones, Shenzhen has a unique history. It is located in southern Guangdong, one of the most affluent provinces in China, bordering Hong Kong, the economic centre of the Far East. Shenzhen was a land of abomination at the beginning of the People’s Republic of China. Enduring natural disasters and economic instability, many fled Shenzhen to Hong Kong to pursue more opportunities. 40 years ago, Deng Xiaoping launched his grandiose economic reformation, with Shenzhen as one of the first cities to testify to his ambition. In merely forty years, Shenzhen has leaped from a nameless fishing village to one of the most influential international metropolises in the world.

As a native of Shenzhen, Lin Zhao draws inspiration from her home city’s remarkable transformation—from a small coastal town to a sprawling urban jungle—to explore the tension between progress and the erasure of memory. This experience, deeply intertwined with her upbringing, embodies the evolving landscape that shapes her narratives. Her work reflects Southern China’s ongoing struggle to preserve its identity in the face of relentless change.

While elevating the quality of life for billions, the economic reformation unintentionally introduced Western ideologies. In Mandarin, the term “80後” refers to people born in the 1980s and 1990s, often likened to the millennial generation in the West. This generation was the first in modern China to experience the transformative influence of television, refrigerators, Western rock music, and Hollywood films, marking a cultural shift toward globalisation. This generation paved a path toward a reimagined future for a nation balancing its ancient traditions with newfound modernity. New waves of thought collide with entrenched traditions, which resist and persevere. Lin, a writer who was born and raised in this magical turning point of modern China, understood how to navigate the uncertainty with her words. She tentatively wades into the rippling waters of uncertainty, searching for a path forward for a generation like hers—confused, curious, and utterly ambitious. Thus, Flowing Creek is a direct response to the time of loss and memories.

It’s impossible to look away from Lin’s work from the perspective of “female writing”. Now that the feminist movement has become an indispensable component of the post-Cold War Western soft imperialism, it has made its way to the other side of the Earth. Lin has reiterated that her works have no feminist element, “I just happened to be a woman”. As a polyglot who masters Mandarin Chinese, she describes this weird feeling of growing up in Flowing Creek: “The term ‘only daughter’ begins to loosen, like a tooth about to be pushed out, leaving a dark, foul-smelling socket: I will no longer be some man’s only daughter, and in that bright, vast moment in early autumn of 2001, I was absent-minded, oblivious to it all.” The tantalising feeling, when a human being slowly begins to come to their very first epiphany—the feeling of not being worthy enough, does not feel great. Zao’er’s story echoes many women who struggled with failure and achievement in the previous generation. A materially secured and fulfilled middle-class life does not guarantee a lot, while everybody is walking on eggshells, in a constant state of precarity, which naturally leaves Zao’er with an unhealable wound, rotten and rancid. She is every single young woman, collectively. Nourishing in the facade created by the abundance of materiality, no one dares to admit that they were not the beloved one, since they were not able to carry on the familial name. These women are fundamentally different than their matriarchal ancestors, but being the pioneer was simply a heavy responsibility for everyone. They could be set free, but no one has guided them through the steps afterward.

Zao’er’s life is in perpetual chaos, as she fails to make genuine connections in school, losing touch with practically the very few female seniors which she could look up to, the constant absence of a father figure, and cannot trace the location of her romantic interest. The root of her indignity resulting in her eventual submission to malevolence is unironically a passive revolt of her life. Zao’er’s inability to accomplish anything in her miserable life was not her fault, in fact, just like how Nabokov built Humbert Humbert, an endearing yet loathful freak, Zao’er is not much different. She is the product of a system under which patriarchy colludes with capitalism, operating altogether as a monstrosity that pushes people to commit the most unspeakable crime. In Zao’er’s case, all the hatred and unfulfillment have been manifested through her supposedly innocent half-brother. To free herself, she had no choice but to murder her brother, which marks the end of her girlhood, and her pathetic life.

Therefore, Flowing Creek seems to interrogate a crucial but often neglected question: Where should “Noras” go, once they decide to walk away from the Doll’s House? Flowing Creek is a microscope, it shows how young women could exert their agency under absolute helplessness and humiliation. The never-ending feeling of being inadequate, emotionally overcharged, and lost, sucking the women of post-economic reform into the abyss.

Lin’s sophomore novel, Tidal Chart, followed an entirely different path. Lin moved from a story reminiscent of a Southern Chinese Madame Bovary to an utterly mesmerising synaesthesia, narrated from the perspective of a gigantic female frog. Before the first Sino-Anglo War (First Opium War), British naturalist H captured a nameless female frog in coastal China and kept her in his private garden, along with other rarities that H had found while he was travelling around the globe. When the war erupted, H committed suicide due to bankruptcy, but the journey of the frog had just begun. Ever since H’s death, the frog has embarked on a life-long drift. The wealthy treated her as a disposable pet, while the indigenous fishermen revered her as a mythological goddess who reincarnated in the body of a female frog that promised to bring prosperity to their descendants. Eventually, the frog managed to find her way to Europe, where she was the symbol of the bygone Tang Empire, fulfilling the distorted and exoticised gaze of Westerners toward the East. The relationship between colonisers and the colonised parallels the connection between the frog and the human world. This parallel is threaded through the entire book: The frog’s journey through human exploitation reflects Southern China’s complex entanglement with foreign influence, as explored by Lin, who conveys a powerful message here: the marginalised can reclaim agency through resilience and self-awareness.

In the novel, Lin re-evaluates the relationship between humans and nature in the Anthropocene. The Anthropocene is a proposed epoch in which human activity has become the dominant influence on Earth’s environment, climate, and ecosystems. Marked by pollution, climate change, and species extinction, it highlights humanity’s lasting impact on the planet’s geology and ecology, first coined by Dutch meteorologist Paul Crutzen. As a former amateur botanist, Lin’s avid passion for plants and their relationship with humans weaves through her writing. Lin bestows plants with liveliness and personas. Chinese literature has taken a step forward in alignment with world literature which seeks to decentre from humans. As humanity gazes at the giant frog, it gazes back at them. Mina dresses it in a morning robe and a sari, asking it to retain its “wild” instincts while learning foreign languages and human etiquette. Yet, it never becomes, as foreigners imagined or hoped, an easily trained pet that is “loyal and passionate to its master and indifferent or arrogant to others.” It is brought to weddings as a mascot, but to it, the bride “is a stranger, dressed in white from head to toe as if in mourning. Foreign little imps run around, tossing petals like spirits and scattering coins by the stream. Everything is whitened to misfortune, and not a single person looks joyful. The living squeezes alongside the dead. Death sits in the chill of the graveyard, looking over like a bricklayer on a lunch break. So, I say foreigners are very strange.”

While humans study the giant frog to satisfy their curiosity for monsters, aren’t they, in the frog’s eyes, greedy and foolish monsters who love to deceive themselves?

Interestingly, H thinks he has captured the frog, yet he doesn’t realise that it was the frog who lured him into the discovery. With the mindset of experiencing whether there is any good cage in the world, the frog willingly enters the cage, scrutinizing everything that confines it, treating the captivity itself as an experiment and thus dissolving the authority of the one in power. In this process, human greed has nowhere to hide. If the middle sand fishers’ worship of the giant frog reveals the hardships of life at the grassroots level—as they live by water yet remain adrift, always at risk of being swept away by the waves—then the foreigners’ study, exhibition, and myth-making around the giant frog symbolises the colonialist’s plunder and gaze upon the East.

Lin once shared that the original protagonist of her novel was a woman from early 19th-century Guangdong. However, she quickly realised that the actual circumstances of women’s lives at that time would greatly limit the story, leading her to settle on a “frog” as the protagonist—a creature that is non-human and amphibious. This choice allowed the character to move more freely between realms, objectively depicting the variety of human experiences and recording the passage of time in a more enduring way. This freedom is also the contemporary significance of Lin’s writing—through the giant frog, she is exploring a freer mode of storytelling. The frog was no human, but her life was a kaleidoscope that encapsulated colonial China through a humane lens. Lin has meticulously created her protagonist as a non-human, a rarity that is so precious that in some way, emblems the fascination of colonial China: “I am a fictional being. I don’t speak of characters, for I am not human at all. I have had many names, each one leaving me, enough to form a second tail. I can speak the water dialect, the provincial city dialect, and English better than pidgin English. A bit of Macanese slang. I have some knowledge of Fujianese, Portuguese, and Dutch. I recognise a dozen or so characters. I am a fictional being, an animal yet to take shape. My all-powerful creator—my mother—was born in 1981 in a workers’ village on Si Ma Road in the provincial city. From the beginning of creation, my mother endowed me with three qualities: curiosity, fickleness, and fear of death. The world was prepared for me at that moment, but it was barren and empty. Characters surged like a vast flood, without direction, without meaning. I lay low. It was the primeval era. Apart from curiosity, fickleness, and fear of death, I possessed nothing else”. This is Lin’s bold attempt to mock and extol an epoch, a century of humiliation, or a century of reestablishment. The human body is a myopic and unfulfilled conduit, failing to lead us anywhere close to the destination. Before the first Anglo-Sino War, China was an Empire enclosed, no undercurrent could make revolutionary changes. It’s innately innocent, blissfully ignorant. However, the canons of capitalism opened up a gate that was paved by gold and tears, bleeding all over. The introduction of opium marks the beginning of modernity and chaos. Many literature works revolve around the actual historical moment such as the fall of the Imperial Qing or the Cultural Revolution, but very few pinpointed their lens on what had happened before. Lin poignantly located the story at a coastal village, where prehistoric relics, fishermen, Christians, alpacas, and disease fused into a holistic miasma. Every single one plays a part in contributing to the imminent catastrophe without knowing it. Tidal Chart captivates the cultural and political tides of the surreally realistic universe, creating an immersive yet thought-provoking excursion for readers.

Thus, Lin chose a creature that allegedly spans millennia, embodying both tenacity and sliminess, to reflect on the greed and vice that pervade our world. This choice inevitably evokes comparisons to Kafka’s infamous beetle in The Metamorphosis or the tree in Han Kang’s The Vegetarian. The frog serves as a profound symbol of the in-betweenness of life and nature, a liminal being navigating the boundaries of existence. Lin suggests that the physical world, as we perceive it, is a construct—a simulation unable to encapsulate the vastness of transformation and impermanence. In this context, we are compelled to seek alternatives. At the centre of this narrative is a hyper-intelligent and sensitive frog, an entity seemingly insignificant yet imbued with immense symbolic weight—greater than anything mortal beings can fully grasp. Through this character, Lin playfully and profoundly probes the definitive boundaries of coexistence, exploring the myriad intersections of living experiences.

In Tidal Chart, feminist themes re-emerge with striking clarity. Lin deliberately narrates the story through the eyes of a female creature—a woman shaped in the form of a frog—mirroring Zao’er’s precarious position during the height of Chinese neoliberalism. Both characters, along with others in the narrative, embody resolute determination and indefinable courage. They are astute, resilient, and willing to take risks. Despite following entirely different paths, both ultimately find reconciliation with themselves and with an unforgiving world. Lin’s stories exemplify Derridean binaries: masculinity versus femininity, rationality versus emotion, nature versus nurture, and the Occidental versus the Oriental. These dichotomies are inherently fragile—poised to be transformed, transcended, and traversed.

In Tidal Chart, Lin illuminates the overlooked richness of Cantonese literature and Southern Chinese dialects, reclaiming a cultural legacy increasingly overshadowed by Mandarin dominance. To write this novel, she consulted materials such as The Dairy of Sea Yue 粤海日志, The Thirteen Hongs of Canon 廣東十三行 Records of Foreigners in Old Canton and Miscellaneous Notes on Old China 廣州番鬼紀錄、舊中國雜記, and Studies on the Tanka People 疍民的研究. Lin embarks on a meticulous literary journey along the Pearl River, comparing old maps with historical landscape paintings to breathe life into Lingnan’s forgotten past. Through her innovative use of traditional Chinese grammatical structures and diction, she emerges as a literary force—an architect of time and space—dedicated to reviving the histories of a region once left in the margins. In doing so, Lin reminds us that literature is not only a vessel for stories but also a powerful means of cultural preservation and rediscovery, leaving an indelible mark on the future of Chinese letters.

How to cite: Wang, Winifred Dongyi. “Rewriting the Southeast Chinese Frontier with Tenderness: Lin Zhao’s Flowing Creek and Tidal Chart.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 29 Jan. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/01/29/lin-zhao.

Winifred Dongyi Wang is a Beijing-born, New York City-based bilingual writer. She graduated magna cum laude with a degree in History in 2023 and earned her MA in Experimental Humanities and Social Engagement from New York University in 2024. During her studies, she developed a profound interest in creative writing and philosophy. An ardent admirer of literature and art, her work seamlessly blends traditional Chinese literary aesthetics with postmodern techniques. She is the author of the novel Dissection of the Moon (2025). {Instagram | X | Email}