Editor’s note: Photographer Daniel Garrett examines debate over a Hong Kong protest photograph used on the cover of After the Fall: Being American in the World We’ve Made, written (2021) by Ben Rhodes, a senior adviser and speechwriter in the Obama White House. Garrett argues that images acquire political meaning through context, authorship, and circulation. He rejects claims of appropriation, criticises American self-centring and reflexive anti-Americanism, and contends the cover’s sombre, defeatist aesthetics misrepresent Hong Kong’s cosmopolitan protest movement while obscuring Western political hesitation and moral failure.

[ESSAY] “After the Fall, Before the Image: On Reading a Hong Kong Protest as Book Cover” by Daniel Garrett

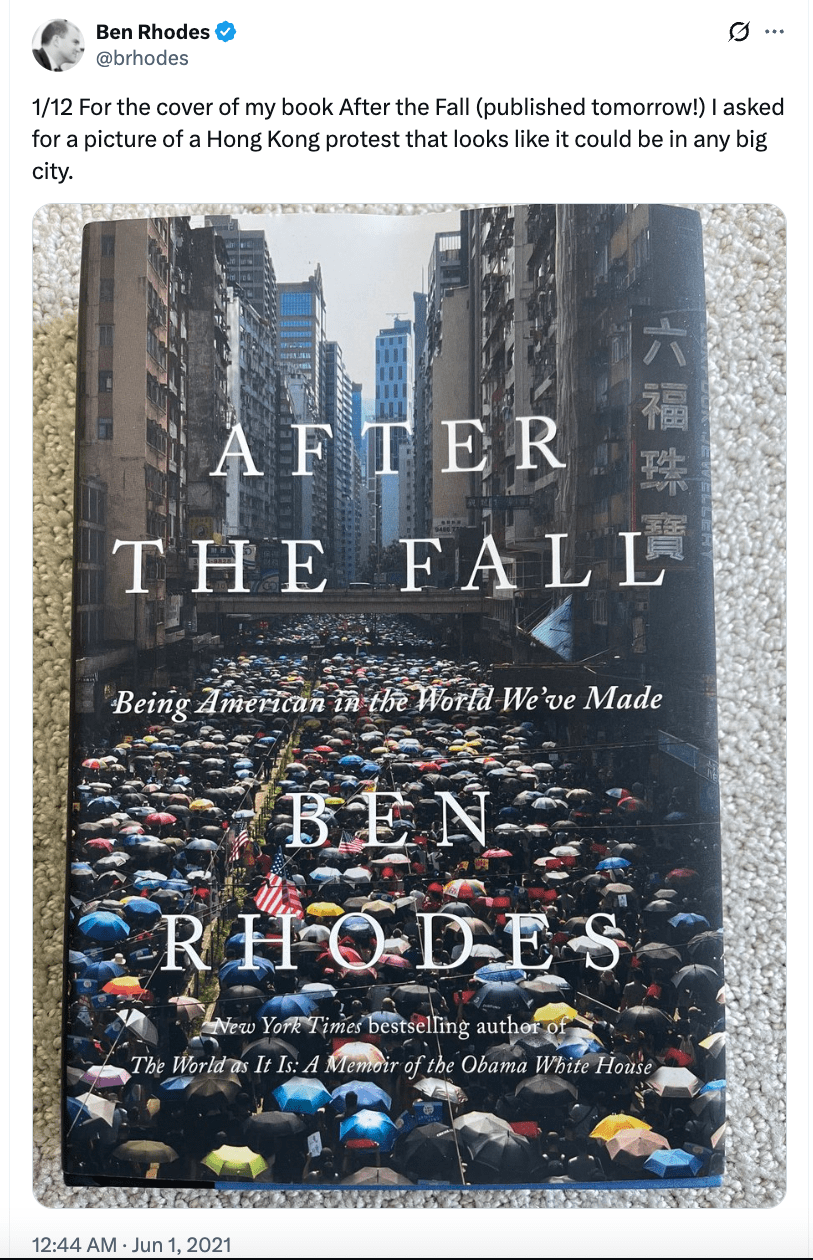

Ben Rhodes’s decision to use a photograph of a Hong Kong protest on the cover of his 2021 book After the Fall: Being American in the World We’ve Made sparked some discussion on Twitter (now X). In a public thread explaining the choice, Rhodes wrote that he had asked for “a picture of a Hong Kong protest that looks like it could be in any big city,” settling on a 2019 photograph by Oliver Haynes that features an umbrella, an object that has become a visual marker of Hong Kong protests since 2014 and that can function as a shield against surveillance, tear gas, and pepper spray.

One critic wrote that the image “succeeds at being both erasure and fetishisation.” Another asked, “Can Americans for once stop centering everything around them, including HK’s protests.” A particularly pointed response questioned Rhodes’s retrospective invocation of Hong Kong activism given the Obama administration’s posture in 2014, accusing him of selective inspiration and political amnesia. What follows is my attempt to think through this controversy by focusing not on the book’s argument, which I have not yet read, but on the image, its framing, and the claims made on its behalf.

}

Images can be read in multiple ways, and, as has often been said, they have careers and lives of their own. The meanings ascribed to them shift over time. They are never encountered in isolation. A book cover is an assemblage, a photograph embedded in typography, subtitle, authorial name, and promotional text. This intertextuality has its own affective force. The cover becomes a new image in itself, constituted by both photograph and text. The textual elements do not merely frame the photograph but generate their own impressions, which then bleed back into how the image is read.

For a viewer who is American-literate and geopolitically informed, and who is familiar with Ben Rhodes, Barack Obama, and the foreign policy of the Obama administration, the declaration that this is “A Memoir of the Obama White House” inevitably brings with it a dense set of associations. These associations can muddy the reading of a photograph of Hong Kong protests, however much one might wish to consider the image on its own terms. Feelings about Rhodes and Obama, including judgments about what I see as the moral and policy failures of that presidency to live up to its professed ideals, are difficult to bracket. This scepticism is, admittedly, a tell. It shapes how I approach Rhodes’s broader project of defending and framing that administration’s actions and inactions.

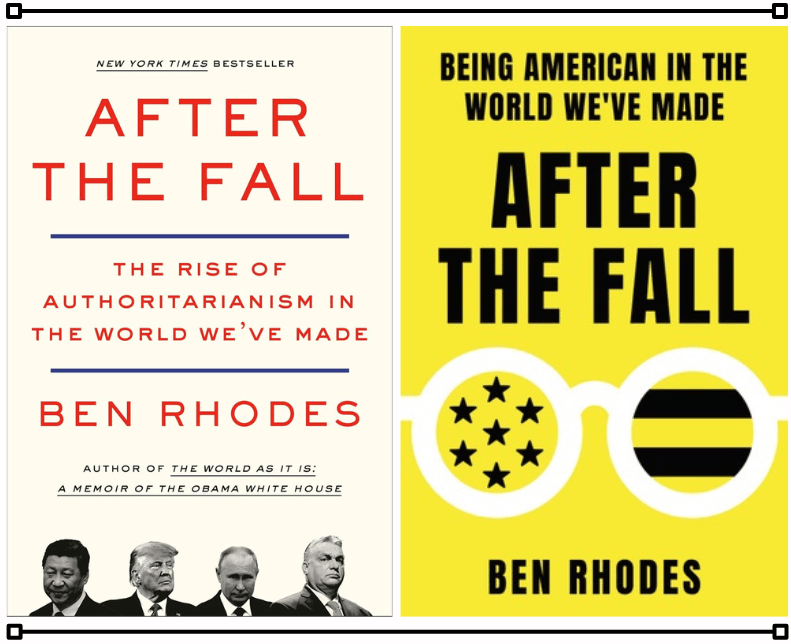

Since the discussion at hand concerns the photograph and the cover image, reading the book is not a prerequisite. It is also possible that one’s interpretation of the image could change, for better or worse, after engaging more deeply with the text. It remains unclear from Rhodes’s tweet how involved he was in the actual selection process, what alternatives were considered, or how much influence the graphic designer and editor exerted. His public explanation is nonetheless useful in clarifying his intent, even as it introduces new points of contention. It should also be noted that the Rhodes-endorsed cover photograph may have been intended by the publisher for a specific market, both geographically and demographically, as alternative covers also exist that contain no visual reference to Hong Kong at all.

I

ndeed, following Ackbar Abbas’s “Politics of Disappearance,” the protesting Hongkongers have been erased and replaced by bland, smallish, black-and-white headshots of authoritarian mafiosos, the “Four Horsemen of the Democratic Apocalypse,” one might argue, set against a pale, yellowish background. These figures are Chinese Communist Party General Secretary Xi Jinping, U.S. President Donald Trump, Russian Federation “President” Vladimir Putin, and Hungarian “Prime Minister” Viktor Orbán. A slight variation in the subtitle likewise shifts the framing of the book and the attribution of responsibility for the authoritarian resurgence, moving from an American hegemonic gaze, “Being American in the World We’ve Made,” to a more amorphous, generalised guilt that deliberately dilutes and obscures Washington, and the West’s, own agency in enabling and tolerating this development, “The Rise of Authoritarianism in the World We’ve Made.”

The fact that Rhodes asked for a particular type of image suggests to me that he may not have been deeply familiar with the vast diversity of photographs produced during the 2019 protests, nor especially emotionally invested in any single image, as many Hongkongers and close observers understandably are. The chosen photograph appears to have been selected because it was thought to represent the book’s claims first and foremost, rather than to offer an assessment or indictment of the Hong Kong protests themselves. In that narrow sense, his reading of the image is as valid as anyone else’s when we are speaking only of the photograph, not of what others feel it ought to represent. Life experiences differ, and those differences shape how we read images and the world.

}

I disagree, however, with the assertion that the photograph and its contextualisation amount to an “appropriation” of “our struggle,” or with remarks such as “We’re not a stamp in your collection.” Such claims often come from a segment of the Left, both in and outside Hong Kong, that responds with knee-jerk hostility to any American reference to Hong Kong protests. These reactions frequently horseshoe into positions that mirror the fantastical narratives of the far Right, positions that I regard as unproductive at best and actively subversive of the aims of the 2019 to 2020 movement, often referred to as the Water Revolution.

This was a Hong Kong that understood itself as part of the world.

Those critics, like Rhodes and his editors, are also advancing their own framings of the protests. There was a time in Hong Kong, before many of today’s younger ideological combatants, when cosmopolitanism was widely claimed as a core value and the city was branded “Asia’s World City.” This was a Hong Kong that understood itself as part of the world. If one genuinely inhabits that cosmopolitan condition, it becomes incoherent to argue that someone “in the world” is appropriating “your” struggle. You are, by definition, part of the same cosmos.

Scholars of contentious politics such as Charles Tilly and Sidney Tarrow have long observed that there is little that is truly novel in the tactics of protest. Tactics, rhetoric, and visual repertoires circulate, particularly when movements recognise each other as operating in solidarity across borders. In this light, it makes more sense to speak of the global impact of the Water Revolution than to frame any reference to it as imperial appropriation. Claims that such circulation is merely another form of imperialism strike me as wrongheaded and, again, counterproductive. They echo, in a different register, the moralising handwringing of moderates who condemned protesters’ use of force in self-defence against Chinese and HKSAR security forces that were attacking demonstrators and occupying the city.

It is also telling that many of those who criticise Western references to Hong Kong protests have simultaneously condemned slogans such as “Hong Kong is not China,” at times labelling them racist. In doing so, they reveal an uncomfortable affinity for Chinese Communist imperialism. Not all critics fall into this category, but many vocal ones do, including some who sought to carve out international attention for their own movements by undermining broader solidarity with Hong Kong.

One plausible reason the photograph appealed to Rhodes and his editors is the presence of three small American flags visible near the bottom of the image. The photograph is clearly cropped, so the original may have included more. These flags visually echo the book’s emphasis on “America(n).” During the protests, American flags were never dominant. They became more visible in 2019 but were still carried by a small minority. This did not prevent Hong Kong, Chinese Communist, American, and Western media from fixating on and sensationalising them. Calls for United States intervention did exist, but they came from a very small group with no real power beyond symbolic gesture. Even so, it was understandable that some Hongkongers might appeal to the United States as a defender of democracy and human rights. At that moment, the country still retained, for many, the image of a “shining city on a hill.”

I do not think the image implies that America caused the protests.

I do not think the image implies that America caused the protests. That claim has long been a Communist Party line, and sustaining it would require far more than the presence of one or a few flags. It would demand the kind of crudely constructed propaganda imagery that circulates in Party-state media as a form of anti-American and anti-Hongkonger visual warfare. Nor do I see either “erasure” or “fetishisation” in the depiction of a mass march of umbrella-carrying protesters. Hong Kong has long been a “city of protests.” What, precisely, is being fetishised here? The city, the protesters, or the umbrellas themselves? The accusation collapses under scrutiny.

As for claims that the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act was ignored, these elide the fact that the Act was eventually passed and obscure the complexity of the United States political system. Support for Hong Kong was strong in the legislative branch in both 2014 and 2019, even as the executive branch remained cautious. Critics often fixate on presidential hesitation as if the United States were an executive-led system, a misconception perhaps understandable given how opaque American politics can appear from the outside, but nonetheless incorrect.

There is, of course, much to criticise about American failures to defend its professed values and to stand up for Hong Kong. But the claim that support was merely performative echoes another tired Communist Party canard, namely that Americans never really cared. That narrative serves Beijing’s interests well.

}

Turning back to the image itself, I do not find it “haunting,” as Rhodes does. I find it defeatist. It does not capture the spirit of the anti-Extradition movement. It resembles an exodus, a grimly prophetic one, given the mass emigration that has followed the imposition of the National Security Law. The marchers move away from the viewer towards a barren cityscape, disappearing beneath an overpass. The overall luminance is sombre, even depressed. Looking at multiple reproductions of the cover, the image appears to have been darkened, likely for design reasons, so that the text remains legible. This is common practice. Hong Kong protest photography also often grapples with extreme contrasts of light and shadow. Without access to the original file and metadata, one cannot say with certainty why this image appears so gloomy.

The cover also feels visually suffocating, hemmed in by concrete canyons. This is striking because, even in the densest protests, I never experienced Hong Kong in this way. Rhodes has claimed that the image depicts a “universal cityscape,” and that this universality conveys how the Hong Kong protests represent global mobilisation against authoritarianism. I do not see this here. To many Asian viewers, the image would register simply as an Asian city. Most American and European cities do not resemble this environment. Nor does the image communicate authoritarianism, or even anti-authoritarianism, in any clear or legible manner. There are no visible symbols of repression, no militarised police, no tear gas, and no weapons. Umbrellas alone, stripped of political signs or slogans, do not bear this weight of meaning without additional context.

In this sense, Rhodes’s claim that the American flags in the image “demonstrate how much America matters to this” feels forced. Many other images could have illustrated that point more convincingly. His broader assertions about the United States as a multi-racial, multi-ethnic democracy also ring hollow in light of the rise of openly fascist movements within the country and the anti-cosmopolitan and anti-liberal horrors of Trumpism. There is, admittedly, a parallel here with Hong Kong, where the imposition of a narrow Chinese Communist identity has erased its cosmopolitan character at gunpoint.

Finally, although it extends beyond the photograph itself, I find Rhodes’s comment that “Hong Kong should be seen as a warning” deeply infuriating. For decades, Hong Kong was already framed as a canary in the mine, a test case for the Chinese Communist Party’s promises. That canary is now dead. Post-2020 Hong Kong bears little resemblance to what came before. Yet Western elites continue to speak as if this were a newly discovered lesson, while shifting their gaze to Taiwan and still hesitating over whether, or how, to act. There were never explicit promises of military intervention for Hong Kong, but there were clear commitments to respond forcefully to the erosion of “One Country, Two Systems.” Those commitments were not honoured in any meaningful way.

Whether in Hong Kong, the United States, or elsewhere, authoritarian and totalitarian forces cannot be wished away with rhetoric, warnings, or unprovocative, defeatist images. As Gramsci observed, this is a time of monsters. Nonviolence has its place, but empty gestures do nothing to stop them.

How to cite: Garrett, Daniel. “After the Fall, Before the Image: On Reading a Hong Kong Protest as Book Cover.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 21 Jan. 2026, chajournal.com/2026/01/21/after-the-fall.

Daniel Garrett (PhD) is an author, documentary photographer, political scientist, and visual sociologist with Securing Tianxia LLC, where he studies Chinese security and visual politics, foreign malign influence operations, image warfare (imagefare), and Beijing’s securitisation of Hong Kong, as well as the visual resistance of the diasporic Hong Kong nation in exile. A doctoral graduate of City University of Hong Kong, he investigated the power politics of “One Country, Two Systems” under China’s new national security framework. He is the author of Counter-Hegemonic Resistance in China’s Hong Kong: Visualizing Protest in the City. Garrett was banned from Hong Kong after testifying at the US Congressional-Executive Commission on China hearing on the 2019 protests. He is a former photographic contributor to Hong Kong Free Press and is also a prolific conservation, nature, and wildlife photographer. [All contributions by Daniel Garrett.]