Ma Ka Fai’s note: These are selected excerpts from my novel Once Upon a Time in Hong Kong III (雙天至尊), forthcoming this year. The story’s protagonist, Hon Tien-Yan, is a passionate martial arts enthusiast and an ardent admirer of Bruce Lee. One day, his master, Willow Beard, shares evocative tales of the mentor-disciple relationship between Ip Man and Bruce Lee. Though derived from second-hand accounts, these stories enthral Tien-Yan, drawing him into a vivid reverie. Ip Man passed away in December 1972, and Bruce Lee’s untimely death followed in July 1973. Drawing upon historical records, I have interwoven my own imaginative interpretations to breathe life into this narrative. My intent has been to pay homage to these iconic figures with the utmost respect and sensitivity. The excerpts delve into the early days of Bruce Lee’s apprenticeship and the poignant moments preceding his departure from Hong Kong. In my conception, the transmission of mastery across generations is imbued with a profound ambivalence—a delicate balance of resolute determination and a bittersweet reluctance to let go.

◯

1. Grandfather

◯

Bruce Lee was born in the Chinese Hospital of San Francisco’s Chinatown, and by the traditional Chinese reckoning, he was destined to be a dragon. It was 1940, the Year of the Dragon in the Chinese zodiac. 27 November, at precisely 7:12 in the morning, during the hour of the dragon. And yet, curiously, his name bore no connection to the mythical creature. His given name was Lee Jun-Fan 李鎮藩, while his English name was Bruce.

His father, Lee Hoi-Chuen 李海泉, a celebrated performer in Cantonese opera troupes, had arrived in the United States at the end of the previous year. He was on tour with the Grand Stage Theatre Company, raising funds for the war against Japan and providing relief for refugees. His wife, Ho Oi-Yu 何愛榆, had accompanied him and became pregnant during their travels, remaining on the West Coast to await the birth of their child. Ho Oi-Yu had initially intended to name their son Yuen-Kam 炫金, meaning “lavish gold,” a tribute to “Old Gold Mountain,” the Chinese name for San Francisco. She envisioned her son flourishing and commanding admiration in this city. But Lee Hoi-Chuen, after furrowing his brow in thought, dismissed the idea. “Kam,” meaning gold, struck him as too vulgar Instead, he settled on Jun-Fan 震藩—a name imbued with resonance and gravitas, echoing across San Francisco. However, a relative interjected: “Is it truly ideal? His grandfather’s name was Lee Jun-Biu 李震彪. Shouldn’t the grandson show a little deference?” And so, 震 was softened to another character with the same pronunciation 鎮, retaining its weight and gravity.

In practice, though, Lee Jun-Fan was a name that lived on paper—on immigration documents and school certificates in Hong Kong. Within the family, he was simply Yuen-Yam 源鑫, his clan name, or more affectionately, Sai Fung 細鳳—“Little Phoenix,” a tender moniker reflecting his cherished place in the family. He had an elder sister, Lee Sau-Yuen 李秋源, and another named Lee Sau-Fung 李秋鳳, as well as an older brother, Lee Jun-Sum 李忠琴. Eight years later, his younger brother Lee Jun-Hui 李振輝 would be born. There had been another brother, but he died young. Convinced that his soul had been taken by the Golden Armour Spirit, Lee’s grandmother imposed a strict tradition: henceforth, every boy in the family would wear girl’s clothing and have their ears pierced until the age of six. Each boy was given a feminine nickname to mislead vengeful spirits. For daughters, it was deemed less of a concern—should misfortune strike them, it was of no great consequence.

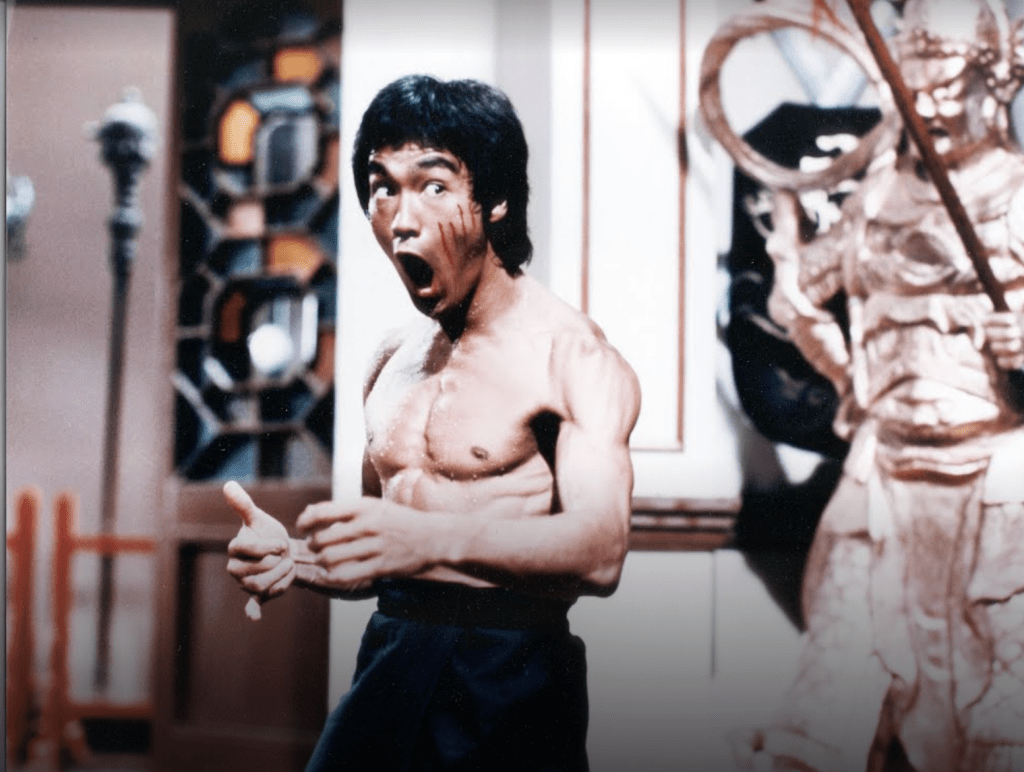

At eleven, Sai Fung formally became the Bruce Lee the world would come to know. Before he turned six months old, he had returned with his parents to Hong Kong, settling in a second-floor apartment at 5 Molin Street, Mong Kok. With many relatives working as actors and directors, he was frequently invited onto film sets, where he played child roles. Using various stage names like Lee Yam 李鑫, Lee Man 李敏, Lee Lung 李龍, and Little Lee Hoi-Chuen 小李海泉, he appeared in six or seven films. When he took on a more prominent role in Father and Son 人之初, the publicity director, Yuen Po-Wan 袁步雲, decided it was time for a new name. Thus, he became Lee Siu-Lung 李小龍—“Dragonling Lee.” “Dragon in the field, dragon in the sky, a dragon undone, and finally a dragon that vanishes without trace.” Through his brief but tumultuous life, he wielded this name like a thunderclap, carving it into the collective memory. He loved the name, and the world, in turn, remembered it.

Bruce Lee

At both the film studio and school, Bruce was a constant source of exasperation for his elders and peers. They nicknamed him King Kong, a moniker that reflected his untamed energy. He darted about, seemingly fuelled by an unrelenting force, as though even the slightest stillness might cause him to unravel. His skin would tingle with a restless urgency, as though his senses—his eyes, ears, mouth, and nose—were scattered across his limbs. Even his thoughts seemed to reside in his fists and feet, coming alive only when his body was in motion. It was through his frenetic gestures that he communicated his joy, anger, and sorrow to the world. Some elders, seeking to temper his boundless energy, taught him Tai Chi. Others introduced him to Hung Ga. Yet instead of calming him, these lessons ignited an even greater fervour within him. He discovered that every movement of his hands and feet could have meaning, that there existed something called “kung fu” that could elevate his boundless energy into an art form. Through kung fu, Bruce Lee began forging an identity uniquely his own. No longer merely an actor playing pretend roles, a son under his father’s shadow, a pupil in his teacher’s classroom, or just another schoolmate, he found in each punch, each kick, a sense of self—solid and breathing, unmistakably alive.

Bruce craved proof of his own vitality, and for him, that proof came in the form of fighting. He fought classmates in the classroom, delinquents on the streets—it did not matter whether he won or lost. What mattered was the thrill, the raw exhilaration of the fight itself. Once, he came home with a swollen eye. His aunt, sitting at the eight-immortal table cracking walnuts for dessert that evening, glanced up and covered her mouth in a laugh. “Sai Fung, another fight? Oh my, you’re just like your grandfather—always quick with your hands and feet. It seems that’s all you know how to do.” Bruce immediately raised his eyebrows, his eyes alight with curiosity. Before he could ask further, his aunt swept the walnut shells into a small wooden bucket beneath the table and began recounting tales she’d heard from his mother about his grandfather. Her voice rose and fell like a Cantonese opera, pausing and resuming as though punctuated by dramatic beats. Before her marriage, she had played dan roles in Cantonese opera troupes. Since then, she’d lived a quiet, childless life, her days a monotonous repetition. It was only through storytelling, with an audience captivated before her, that she seemed to reclaim a flicker of vitality.

Bruce’s grandfather, Lee Jun-Biu, was born in Jiangwei Village in Shunde, Guangdong. As a child, a high fever damaged his throat, rendering him mostly mute. The villagers called him Mute Biu. He took to martial arts, practising diligently and speaking little, and eventually became renowned for his skills. He built a formidable reputation in the ring and later as a bodyguard in Foshan, providing for a household of eight or nine through his earnings. Stories circulated in the village of how he once encountered bandits on a forest path. His companions either fled or were injured, leaving him alone to face ten men. Though wounded and stabbed multiple times, he wielded a single staff and drove them away. In the Lingnan region, even the mountain bandits came to know and fear him, dubbing him the Mountain-Shaken Tiger. Years later, the Tiger retired and returned to his village. His son, Lee Hoi-Chuen, grew up and moved to Guangzhou to study Cantonese opera, eventually becoming a renowned comedic actor known as the King of Clowns in the opera world. When Lee Hoi-Chuen returned to the village in triumph, dressed in fine clothes, Jun-Biu—by then somewhat senile—extended his hand, demanding money. “I’m heading out to roam the world again!” he declared with the bravado of his younger years. Lee Hoi-Chuen scoffed and refused, but when his father grew violent, he reluctantly handed over the cash. A few days later, Jun-Biu returned home, battered and silent, his money gone and his body covered in bruises and welts. No one ever uncovered what transpired during those days. Some time later, Jun-Biu passed away in his sleep, clutching in his hands two small iron balls he had used to strengthen his wrists.

His aunt tapped Bruce lightly on the forehead with her finger and chuckled, “Maybe you’re your grandpa reborn, sent to complete the unfinished ambitions he left behind.”

Bruce shivered at the thought. “Could that be true?” he wondered. “If I’m Grandpa’s reincarnation, am I still myself? Am I living my own life, or am I merely his second chance to return to the world?” A strange warmth stirred within him. “What kind of world was Grandpa trying to conquer? Did the Mountain-Shaken Tiger pass his martial skills down to me? He fought ten men at once—how many could I defeat with my fists?” The aunt’s offhand remark sparked a tempest in the thirteen-year-old boy’s mind. He suddenly saw himself as one of the young warriors from the martial arts comics he loved so much, standing on the edge of a cliff, burdened by a tremendous secret about his lineage. Overhead, a colossal roc circled and cried out, casting its shadow over his uncertain future.

In the midst of his thoughts, the front door creaked open. His father had returned, carrying his heavy bag of stage costumes. Bruce darted back to his room, only to slip out moments later into his aunt’s quarters. There, he took down a photograph of his grandfather from the wall and retreated to his own room. Sitting cross-legged on the floor, he studied the photograph intently. The longer he stared, the more convinced he became of the uncanny resemblance between them. The eyebrows, the eyes, the sharp, thin lips—and most striking of all, the pointed chin that jutted forward as if challenging the world itself. It was a chin that spoke of defiance, a relentless will to command the world to bow before it. From the next room came the sound of his father coughing and clearing his throat. Bruce frowned. He respected his father and understood the care and love his father showed him. But he could not imagine himself following the same path—spending a lifetime on stage making people laugh for a living, no matter how much money it might bring. Respect and admiration held little appeal for him. What he craved instead was fear and awe. Bruce felt as though his grandfather’s power had already coursed into his veins. He stood firm in this world, and the world, in turn, rested upon his fists. To lower his fists would be to allow the world to crumble.

Rising to his feet, Bruce walked over to the mirror and gazed at his reflection. He yearned for his body to grow faster—taller, stronger, more imposing. Faster, always faster. He raised his fists before his eyes, wishing life, like a film, could be edited and enhanced with special effects. If only he could blink and see his fists instantly grow larger, harder, more powerful. In his imagination, he stood on an endless plain, his fists whirling, his feet kicking high into the air, unleashing a gale that tore through everything in its path. Grass and trees bent and broke beneath his might. His life, for now, was ordinary, tethered to the realm of common existence. But young Bruce had already made a vow: he would live his life as if it were more vivid, more extraordinary, than any movie.

◯

2. Apprenticeship

◯

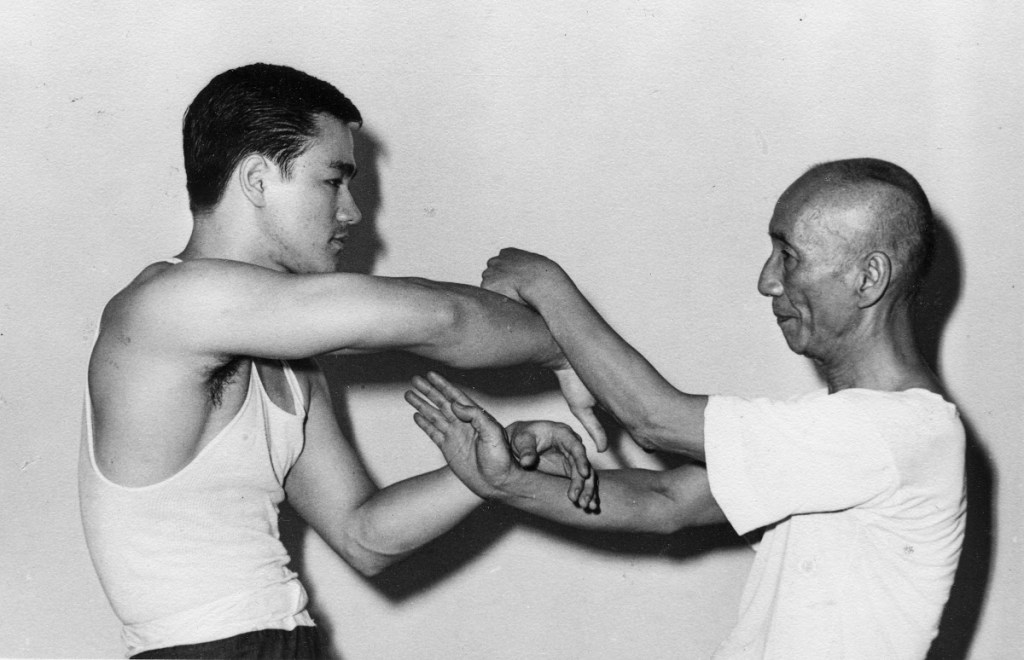

Bruce was fifteen when he became Master Ip Man’s apprentice. Their meeting took place on Li Tat Street in Yau Ma Tei. At that time, Ip taught Wing Chun at the Kowloon Hotel Employees Union. His existence was modest; at night, he would unroll a canvas bed on the shop balcony and sleep there. Over the years, he relocated several times—teaching at various workers’ unions in Sheung Wan, Stanley Street in Central, and later in Sham Shui Po, on Hai Tan Street and Yu Chau Street at the Sam Chi Temple. To others, his life appeared to be one of transience, but Ip was content. For as long as he remained tethered to Wing Chun, he felt no sense of deprivation.

By then, the young Bruce Lee had acted in over a dozen films and was already a well-known actor. Yet fame had done little to temper his rebellious streak. He frequently found himself embroiled in fights at school and on the streets. He formed a gang with several friends, calling themselves the Eight Tigers of Kowloon, with Bruce as their leader, his nickname The Little Overlord. When Bruce heard that Wing Chun excelled in short-distance combat—a perfect fit for someone with his severe nearsightedness—he sought out Ip on Li Tat Street. On their first meeting, Ip asked Bruce to demonstrate his skills. Bruce tilted his sunglasses up the bridge of his nose and swiftly unleashed two or three crosses of chain punches before turning to the wooden dummy, delivering a few horizontal kicks. He ended his performance with a dramatic flourish, standing with a self-satisfied smirk. Bruce respected Ip’s martial prowess but harboured no doubt that he would one day surpass him. There was no one he truly regarded as his equal. Ip, watching carefully, saw potential. But he also noticed Bruce’s flat feet and the instability of his stance, his steps light and wavering. Quietly, he sighed—it was a pity. By the way his features were set, Bruce’s destiny seemed fated to burn brilliantly but briefly.

Ip asked him, “Shall we start tomorrow?”

Bruce shot back, “Can we start today?”

Looking up at the taller boy, Ip smiled and replied, “You may wish to begin today, but your teacher prefers to start tomorrow.”

In Ip’s mind, there were distinctions between those who came to his school. Most of the seventy or eighty people who trained there were merely students. They paid their tuition, which Ip accepted in good faith, and he taught them with sincerity. They, in turn, learned diligently, and the relationship ended there—a simple transaction, nothing more. A smaller group of five or six, however, stood out for their natural talent and dedication to martial arts. Ip regarded them as disciples. To these individuals, the money they handed him was not tuition but a gesture of respect. The teaching and learning in these relationships ran deeper. He would take an active interest in their progress, often inviting them to the North River Restaurant for late-night tea and Cantonese opera, or to Sham Shui Po for leisurely walks, during which he would recount tales of his past in the martial world. Soon after Bruce joined, Ip realised that he belonged to neither category. Ip admired his talent and determination, and Bruce, in turn, demonstrated his commitment and work ethic. He spent six or seven hours each day at the studio, practising relentlessly, never once voicing fatigue. While most students viewed Wing Chun as a way to keep fit, and disciples approached it as a discipline to refine their skills, Bruce saw martial arts as the defining purpose of his life. Every movement he practised, every strike he executed, was imbued with an unrelenting ambition. Through Bruce, Ip glimpsed the same passion and single-minded devotion that had characterised the great masters of old. Though Bruce’s stage name was Dragonling, he aspired to be more—a Great Dragon, the singular dragon of the martial arts world.

Bruce’s punches were powerful and fast. When sparring with his fellow students, it was not uncommon for an unfortunate partner to end up with a bruised face or a swollen nose. In his youthful exuberance, Bruce rarely held back during matches, often provoking the ire of his peers. Both on the streets and in the training hall, he was The Little Overlord. But Bruce had a weakness: his horse stance was unsteady. If his punches missed their mark, he often struggled to recover in time, leaving himself vulnerable to counterattacks. One day, Bruce sparred with his senior, Wong Dong-Leung. Bruce launched a flurry of kicks and punches, but Wong skilfully neutralised the attacks with retreating stances and turning stances. Then, seeing Bruce’s footing waver, Wong capitalised on the opening, delivering a suspended palm strike aimed at Bruce’s jaw. The strike stopped just short of landing—a gesture of restraint and control. But Bruce, unwilling to concede, suddenly bent forward and attempted to bite Wong’s fist. Wong, reacting swiftly, shifted his fist into an open palm and delivered a resounding slap to Bruce’s face. The sharp sound reverberated through the training hall. Bruce touched his cheek, feeling the heat rise to his forehead. Anger surged through him, and he shouted at Wong, who had already turned and sat down to rest. “Don’t walk away! Rematch!”

Wong snorted in response. “Learning to lose, little brother, is the most important life lesson.” Five years older than Bruce, Wong had been training under Ip for four years and revered their teacher as a father figure—his respect deeply rooted in the Confucian ideals of loyalty and filial piety.

Bruce refused to back down. “I didn’t lose! A fight isn’t over until you’re knocked down and can’t get back up!”

The air in the room grew tense. Wong’s face darkened as he remained silent, wiping his face with a towel.

In the corner of the hall, Ip, who had been teaching another group of students the chi sau (clinging hands) technique, finally spoke. His tone was calm, unhurried. He addressed Wong first. “Bruce isn’t wrong. In a fight, as long as you haven’t been knocked down, you have the right to keep fighting.” Then, turning to Bruce, he added, “But your senior isn’t wrong either. You have the right to challenge, but he has the right to decline. And when Dong-Leung spoke of ‘knowing how to lose,’ he wasn’t talking about fighting. He was talking about life. Bruce, when you spar with your Wing Chun fellows, it’s not a fight. It’s a test of techniques, nothing more.”

◯

3. FAREWELL

◯

On 29 April 1959, Bruce Lee boarded the President Wilson ocean liner, carrying with him a hundred U.S. dollars given by his father. He was headed for America—San Francisco, his birthplace. On that day, he was precisely 212 days shy of his nineteenth birthday. The decision to leave had been made in haste. Bruce’s frequent sparring matches and street fights had earned him not only admirers but also jealousy and animosity. He had crossed paths with gangsters and troublemakers, and danger seemed to shadow him from all directions. A family friend in the police force discreetly informed Hoi-Chuen that Bruce had injured the son of a wealthy businessman. The businessman’s wife had filed a report, and the police could arrive to arrest him at any time. After some deliberation, Hoi-Chuen and Oi-Yu decided to send their son to America to study. For most young men, this would have been a cause for celebration—a chance to study abroad and explore new horizons. But for the Dragonling, it felt like an exile, an ignoble retreat from trouble.

At first, Bruce was deeply resentful, even contemplating defying his parents. Yet as the day of his departure approached, a strange excitement began to stir within him. “Exile,” he mused, “is simply another form of roaming the world.” Was this not, after all, his grandfather’s dream? And, more importantly, was it not his own? The world of Hong Kong was too small, too shallow. It was not that Hong Kong was pushing him out—it was that he refused to be confined. “I am a dragon,” he told himself. “A dragon does not belong in shallow waters. I will not allow it. The world beyond awaits me. I am coming. I will stir the winds and churn the seas, and the world will fear me.”

In the ten days leading up to his departure, Bruce was subjected to a relentless series of farewell banquets hosted by relatives and friends. One meal after another, each filled with tearful goodbyes and heartfelt speeches. For Bruce, the hardest part wasn’t the overindulgence or the aching fullness in his stomach but the exhausting need to match their emotions, to feign a reluctance he did not feel. Each evening, after the gatherings ended, he walked home alone, venting his restless energy along the way. He punched at objects he encountered—rat traps hanging from lampposts, wooden mailboxes outside homes, and even iron ones bolted to gates. The sound of his fists rang out, bam, bam, bam, as if he were sending a warning to the world. “I am coming. I am coming. Bruce Lee is coming. Are you ready?”

Bruce’s Wing Chun fellows also gathered to bid him farewell on his last night in Hong Kong. Yet beneath their outward expressions of reluctance lay a quiet sense of relief. They were, after all, glad to see him go. They had long harboured resentment toward Bruce, dissatisfied with how he practised Wing Chun in ways that seemed to stray from tradition, and irritated by his overbearing confidence—his conviction that he was destined to become the greatest martial artist of all time. As the evening drew to a close and the group dispersed, Ip called Bruce to accompany him back to his home in Lei Cheng Uk Estate. Once there, Ip Man asked his partner to take the children to the park, leaving him and Bruce alone. They stood by the wooden dummy, going over the forms and techniques Ip had taught him. They sparred a few rounds of chi sau, their hands gliding and pressing against one another in fluid movements. But suddenly, Bruce applied more force than usual, using bong sau (wing-arc hand) to pin down Ip’s hand before swinging his fist upward. His punch hurtled toward his teacher’s face with alarming speed. Ip, calm and unhurried, bent at the waist and countered with a horizontal palm strike. The back of his hand lightly touched Bruce’s waist, halting the younger man’s momentum. Their eyes met for a brief moment before Bruce lowered his head, his face flushed with shame. “I’m sorry, Sifu. I didn’t mean to catch you off guard.” Ip smiled, “Why apologise? You didn’t manage to hit your teacher, did you?” But Bruce remained troubled, genuinely remorseful. He couldn’t understand why he had failed to restrain his strength. To attack one’s teacher, especially without warning, was the gravest of offences. He assured himself it hadn’t been intentional—at least, he wanted to believe it wasn’t. Ip, however, was not offended. To him, a student’s desire to surpass their teacher was only natural. In fact, it was essential. “To excel beyond the master” was the highest form of ambition in martial arts. The blue must always see the indigo from which it came as its rival. And yet, no matter how skilled the disciple became, the victory could never truly belong to them alone; a disciple was, after all, shaped by their master’s teachings. Even if the student triumphed, the master had not truly lost.

After their sparring, the two sat down to wipe away their sweat and drink hot tea. Ip looked at Bruce and said, “Come, let’s take a walk.”

The two walked leisurely from Lei Cheng Uk Estate to Tai Nam Street, then onward to the Sham Shui Po Pier. The streets were shrouded in darkness, shadows shifting under the arcades. Streetwalkers stood beneath the overhangs, their laughter and flirtatious calls drifting on the breeze, salty and briny, like the wind blowing in from the sea. Ip turned to Bruce and joked, “When you get to America, don’t waste your time fooling around with women there. It’d be a shame to squander all your martial arts training.”

Bruce, ever cheeky, replied, “Wouldn’t it be a waste not to put Wing Chun to good use on them? It’s for our glory!” Ip raised a hand, feigning a slap to the back of Bruce’s head, and spat, “Rascal!” Bruce dodged, laughing loudly as he skipped a few steps ahead. Suddenly, he turned around, his face alight with mischief. “Sifu, there’s something I’ve always been curious about, but I’ve never dared to ask.”

Ip gave him a sidelong glance, intrigued by what might be coming. Bruce stopped in his tracks, his expression turning serious. Then, to Ip’s surprise, he asked, “Sifu, why do you like your partner?”

Ip froze for a moment, then clasped his hands behind his back and continued walking, his head lowered. As he moved, he spoke almost to himself, his voice soft and deliberate. “She enjoys watching me practice kung fu. And I like that she enjoys watching me practice kung fu.” A man, Ip thought, needs a pair of eyes that look up to him—woman’s eyes, specifically. A man’s admiration wasn’t unwelcome, but it wasn’t enough.

Bruce nodded, though he only half-understood. “Mm,” he said thoughtfully, before hurrying to match Ip’s stride. But then Ip stopped, turned, and looked directly at him. “Why do you like martial arts?” he asked.

The question didn’t faze Bruce. From the moment he began training, he’d known the answer. The world could bear witness—he understood exactly why he threw every punch, why he delivered every kick. Without hesitation, Bruce declared, “Martial arts make me feel strong. I’m a strong person, and I like being strong.” He paused, then tilted his head, his tone curious. “What about you, Sifu? Why do you like martial arts?”

Ip Man shrugged lightly, a small smile forming. “For the opposite reason. Wing Chun taught me to be soft, like wind, like water. Wind has no form. Water has no shape. And yet, they are unstoppable.”

The two of them walked side by side, crossing several streets. Bruce spoke at length about his plans for America: enrolling in high school, taking on part-time jobs to earn money, finding a martial arts studio to continue his training, and eventually, when the time was right, opening his own. Ip listened in silence. Then, without warning, he turned slightly and delivered a light, swift palm strike to Bruce’s chest, precise and measured. Bruce let out a startled “Ah!” and looked at his teacher, bewildered. Ip smiled. “I’ve always wanted to visit America,” he said, “but I’m too old now—it’s not something I can do. That strike just now, think of it as your teacher’s way of going with you. Bruce, take Wing Chun with you to America. Show them what it’s all about.”

Bruce was struck speechless. The prospect of boarding the ship the next morning to leave Hong Kong, crossing vast oceans and unfamiliar lands, filled him with both ambition and trepidation. He had no idea what the world’s martial arts scene would be like. But his teacher’s words that night gave him a sense of strength and purpose he hadn’t felt before. It wasn’t merely about bringing Wing Chun to America; it was about proving its value to the world and, one day, returning it to Hong Kong with honour. As these thoughts swirled in his mind, Ip suddenly said, “By the way, show me a couple of moves from the Jeet Kune techniques you learned from Siu Hon-Sang.” Siu Hon-Sang 邵漢生, a stunt performer from the film studios, had taught Bruce a few Jeet Kune strikes. Bruce obliged, throwing two quick chain punches into the air. Ip nodded approvingly, a faint smile on his face, and beckoned Bruce with a curl of his finger to attack him head-on. Following his teacher’s command, Bruce threw a third punch. To his astonishment, Ip neither dodged nor blocked. Bruce instinctively pulled his punch back mid-air, but Ip stepped forward into the blow, allowing Bruce’s fist to land softly against his left shoulder with a light thud.

The muted sound startled Bruce. He gasped. “Sifu, are you all right?”

Ip waved him off with a small gesture. “I’m fine. Your teacher can take it.” He added, “Wing Chun is a treasure, but like any treasure, it has its limits. Treat that punch as though it’s defeated your teacher—as though it’s opened the way for Wing Chun to grow. When you get to America, have the courage to walk your own path, to cross your own bridges.”

Bruce felt the weight of his teacher’s kindness. A warmth surged in his chest, but he bit his lip, determined to hold back tears. A man does not cry, he reminded himself. He would forge his way forward with fists of steel. With a quiet smile, Bruce rubbed his teacher’s shoulder gently, and their eyes met in a moment of shared understanding.

Bruce accompanied Ip back to Lei Cheng Uk Estate. At the door, as they were parting, Bruce turned and asked one final question. “Sifu, in all the martial arts world, who do you admire most?”

“Who else could it be?” Ip replied with a faint snort. “Of course, my Sifu.”

“And why?” Bruce pressed.

Ip paused for a moment, then said simply, “Because he was my Sifu.”

◯

4. Two Elegiac Couplets

◯

On 1 December 1972, Ip passed away at Tung Choi Street in Sham Shui Po. In the mourning hall, a couplet written by his disciples hung solemnly:

The chilling wind now takes the steadfast leaf, the earth grows dim, the skies begin to cry. The gentle rain would soothe our aching grief, yet noble hopes are lost, and dreams run dry.

Bruce, unaware of the funeral arrangements due to a lack of communication from his Wing Chun fellows in Hong Kong, did not attend the ceremony. Instead, he paid his respects privately, burning incense at the Wing Chun Athletic Association on the night of the thirty-seventh-day family memorial service.

On 20 July 1973, Bruce Lee died suddenly at Cumberland Road, Kowloon Tong. At his wake, a couplet written by friends was displayed:

Two years of friendship under moonlit skies; their brilliance lit the path with radiant glow. A sudden farewell cry where dragons and tigers lie; no hero now remains for kindred souls to know.

After the funeral, his body was transported by a chartered plane to Seattle, Washington, where he was laid to rest.

Bruce Lee and Ip Man

How to cite: Song, Chris and Ma Ka Fai. “Master Ip and the Dragonling.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 18 Jan. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/01/18/dragonling.

Ma Ka Fai 馬家輝 holds a Bachelor’s degree in Psychology from National Taiwan University and a Doctorate in Sociology from the University of Wisconsin, USA. His professional career spans an impressive array of fields, including journalism, magazine publishing, advertising, and academia. Among his celebrated essay collections are Dying Here Isn’t So Bad (死在這裡也不錯), Uncle (大叔), Light and Shadow (明暗), and Silent Love (愛戀無聲), to name but a few. His novels Once Upon a Time in Hong Kong I (龍頭鳳尾) and Once Upon a Time in Hong Kong II (鴛鴦六七四) have earned numerous accolades, including the Taipei International Book Exhibition Grand Prize for Fiction and a place among Asia Weekly’s Top Ten Chinese Novels. These works have been translated into Korean and French, extending their acclaim to international audiences. Ma Ka Fai’s forthcoming novel, Once Upon a Time in Hong Kong III (雙天至尊), is anticipated for release in 2025.

Chris Song (translator) is a poet, editor, and translator from Hong Kong, and is an assistant professor teaching Hong Kong literature and culture as well as English and Chinese translation at the University of Toronto. He won the “Extraordinary Mention” of the 2013 Nosside International Poetry Prize in Italy and the Award for Young Artist (Literary Arts) of the 2017 Hong Kong Arts Development Awards. In 2019, he won the 5th Haizi Poetry Award. He is a founding councilor of the Hong Kong Poetry Festival Foundation, executive director of the International Poetry Nights in Hong Kong, and editor-in-chief of Voice & Verse Poetry Magazine. He also serves as an advisor to various literary organisations. [Hong Kong Fiction in Translation.] [Chris Song & ChaJournal.]