📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

Click HERE to read all entries in Cha on Idol, Burning.

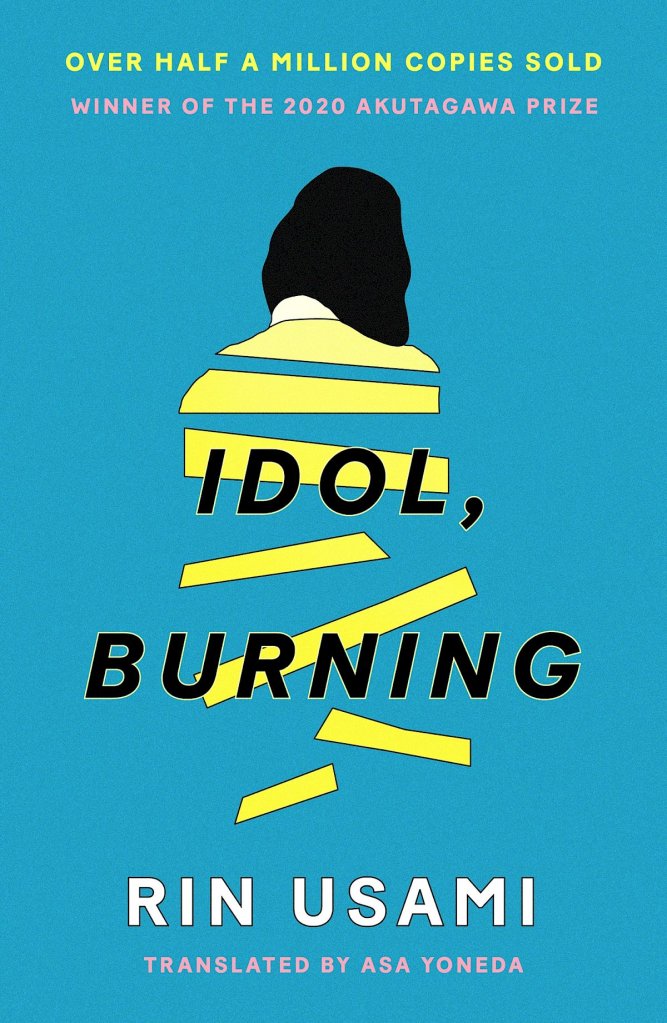

Rin Usami (author), Asa Yoneda (translator), Idol, Burning, Canongate, 2022. 96 pgs.

Rin Usami’s Idol, Burning (『推し、燃ゆ』, 2020) offers an incisive exploration of the world of Akari, a devoted idol fan, capturing the global phenomenon of idolatry, especially prominent in the K-pop and J-pop waves. The story’s theme resonates deeply with Japanese readers, thanks to the popularity and success of Oshi no Ko (『推しの子』), a manga serialised between 2020 and 2024, which was swiftly adapted into both an anime and a drama series. What sets Idol, Burning apart is its profound psychological focus, offering a nuanced portrayal of Akari, delving deeply into her personal experience of oshikatsu—the dedicated activities and rituals associated with idol worship.

The story commences with a scandal involving Akari’s oshi (favourite idol), Masaki Ueno, who punches a fan—a controversial incident that culminates in his withdrawal from idol life following one final live concert. The details of the altercation, including Masaki’s motivations, remain shrouded in mystery, and Akari herself shows little interest in uncovering the truth. Her devotion to Masaki began during a performance where he played the role of Peter Pan, a moment that utterly captivated her. From that point on, her oshi consumed almost every aspect of her daily life. As a high school student, Akari takes on part-time jobs to sustain her passion, saving for concert tickets, CDs, and merchandise featuring her idol. Her all-encompassing dedication comes at a significant cost. Her academic performance suffers, and she eventually withdraws from school.

Akari’s obsession with her oshi may initially arise from his dazzling performances in movies and on stage, but on a deeper level, significantly, her oshikatsu serves as a sanctuary from the struggles of her daily life. This escape mirrors the metaphor of Neverland in Peter Pan, symbolising a desire to remain in a state of innocence and avoid the burdens of adulthood. Akari is often compared unfavourably to her more accomplished sister, Hikari. In one particularly poignant scene, readers can empathise with Akari’s (self-)frustration as she struggles to recite multiplication tables or the alphabet, while their mother show clear favouritism toward Hikari during bath time. Similarly, a tone of frustration pervades another scene where Akari fails to memorise the correct stroke order for kanji during a school test.

In sharp contrast, Akari thrives in writing blog posts about her oshi, which attract the attention of fellow Masaki Ueno devotees who subscribe to her blog and leave encouraging comments. This glaring discrepancy between her difficulties in real life and her success in oshikatsu underscores why idol worship becomes her refuge—a realm where she feels capable, appreciated, and liberated from the pressures of daily existence.

Akari, who narrates the story in the first person, confesses her fear of losing her “backbone”—the personal world she shares with her oshi—as the final live concert approaches its conclusion. While her devotion to the idol is often blamed for her poor academic performance, it can equally be seen as her sole source of solace in a world where she feels profoundly misunderstood by almost everyone around her, apart from her virtual friends and fellow Masaki Ueno fans. Both her mother and sister attribute her unsatisfactory academic results to her oshikatsu, dismissing it as a fruitless obsession. At work, Katsu-san, presumably a senior colleague at the restaurant, derides her idol worship, advising her to “get to know some real men before she misses the boat.” Following her decision to leave high school, her family increases the pressure on her to secure a full-time job. This escalating tension pushes Akari to seek an outlet for her frustrations, mirroring how individuals often turn to belief systems—whether religious or otherwise—as a means of finding meaning, purpose, or escape in life.

Asa Yoneda’s English translation is highly accessible, preserving the straightforwardness of the original text and capturing the authentic voice of the narrator, a high school girl. Notably, scenes that present particular challenges in translation—such as Akari’s heartfelt confession about her struggles with the kanji test—are rendered with impressive fluidity. However, the nuances of the conversations between the two sisters, as well as the casual, colloquial tone of SNS comments, prove more difficult to fully convey, occasionally losing some of the layered subtlety of the original.

A striking difference in writing style becomes apparent when comparing Idol, Burning with Rin Usami’s debut novel Kaka (『かか』, 2019), and her third novel Kuruma no Musume (『くるまの娘』, 2022). In Kaka, for instance, the nineteen-year-old protagonist, Ūchan, narrates in the second person, seemingly addressing her younger brother, Mikkun. The story features an abundance of unique dialects created by Kaka, the siblings’ mother. The prose in Kaka is long, intricate, and thought-provoking, forming a stark contrast to the direct and unembellished style of Idol, Burning. Usami’s third novel, Kuruma no Musume, adopts a third-person narrative interspersed with numerous flashbacks, with the central plot following Kanko on a car journey to her grandmother’s funeral. The narrator in this novel appears noticeably more measured and mature compared to the raw, emotionally charged voice in Idol, Burning.

Despite their stylistic differences, Rin Usami’s three novels are unified by a central theme: belief. In Idol, Burning, Akari’s belief revolves around her oshi, Masaki Ueno, whose presence provides her with purpose and escape. In Kaka, Ūchan’s oshi was once her mother, Kaka. The family had been harmonious until her father, Toto, betrayed his wife through an affair, driving Kaka to seek solace in alcohol. Similarly, in Kuruma no Musume, Kanko’s idol was her father, a figure of admiration and stability, until her elder brother’s departure from home disrupted the family dynamic and altered her perspective.

One will have to wait for Rin Usami’s fourth novel, but so far, it seems the author is deeply interested in examining the complexities of family dynamics. Usami delves into how both external factors—such as an idol scandal in Idol, Burning or a marital affair in Kaka—and internal forces, including familial pressure and shifting relationships, can destabilise the delicate balance within a family.

Bibliography

▚ Rin, Usami (2022 [2019]). Kaka. Kawadebunko.

▚ — (2023 [2020]). Oshi, moyu. Kawadebunko.

▚ — (2022). Kuruma no musume. Kawadeshobōshinsha.

How to cite: Au, James Kin-Pong. “Belief, Devotion, and Estrangement in Rin Usami’s Idol, Burning.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 15 Jan. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/01/15/burning.

James Kin-Pong Au is a Master’s graduate of both Hong Kong Baptist University and the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London. He is currently a PhD candidate at the University of Tokyo, writing his dissertation about the relation between history and literature through close readings of East Asian historical narratives in the 1960s. His research interests include Asian literatures, comparative literature, historical narratives and modern poetry. During his leisure time, he writes poetry and learns Spanish, Korean and Polish. He teaches English at Salesio Polytechnic College and literature in English at Tama Art University. [All contributions by James Kin-Pong Au.]