📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

Click HERE to read all entries in Cha on In the Mood for Love.

Wong Kar-wai (director), In the Mood for Love, 2000. 98 min.

I have been haunted by the same film for twenty-five years. I am haunted by Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love—haunted by the sublime images of this film that remain somehow beyond words, somehow more powerful than what the intellect can capture and truly seize.

It is, and has always been, the slow-motion scenes in this film that affect me the most deeply and still wound me today—wounds that are, in fact, hard to explain, since these scenes contain nothing but completely harmless and utterly mundane activities, verging almost on boredom: we see a woman descending a set of stairs; we see a man crossing her on her way; we see smoke rising from an ashtray and dispersing in the light of a lamp; we see rain falling on the dark pavement of a street. Nothing could be less troubling or less spectacular—nothing could be less wounding or dramatic. And yet, these images and simple actions are saturated with emotions and seem to condense drama—the drama of love, the drama of being—into a sharp and potentially murderous tool.

Through Wong Kar-wai’s camera lens, through the lenses of the protagonists and the lens of love, the everydayness of everyday things is transformed into a spectacle, and what is otherwise utterly common appears suddenly greatly dramatic. Surely, part of this effect, part of this drama, is closely linked to Wong Kar-wai’s use of slow motion, which prolongs every movement, stretches every gesture, and transports the ordinary and the mundane into a different time—a time that is significantly richer and fuller than any ordinary experience.

In his writings on film, Gilles Deleuze uses the term “time-images” to describe such a cinematographic unfolding of time, in which time itself takes on a new significance and meaning and becomes, in several aspects, more important than even the main characters themselves: time as a force that affects bodies, time as an energy that stretches and transforms humans beyond any human control. But if time plays an equally important role in Wong Kar-wai’s film, it is, however, no longer an impersonal force but a deeply personal and subjective one—a force that cannot be separated from the main theme of this movie: the force of love.

In Wong Kar-wai’s film, time and love are coupled in the following way: love is a time that is full—beautifully and unbearably full of signs, meanings, and images. Cinema and love resemble each other in this way, both being grand manufacturers and producers of images. To be in love is to enter a kingdom of images—a land of details, of movements, of gestures that suddenly appear spectacular, enchanting, enthralling. To be in love is to be overflowed with images and to find oneself transported into a time, a duration, that is, in every sense, saturated—saturated with signs and signification: the woman descending a set of stairs is no longer simply descending the stairs but descending them in a significant and meaningful way; the smoke rising from the ashtray is no longer simply rising from the ashtray but rising in a speaking and important manner.

Love is signification and semiotics intensified, gone wild, gone mad even—and love has a tragic dimension precisely because of this intensification and madness: life at its fullest is also life at its most unbearable. No foundation can support these saturated images, these saturated signs, that are destined from the beginning to go under. Love in its extreme is an impossible love that must either become something else—something more livable and bearable, something less ecstatic and more common—or must disappear altogether. Tragedy is present in all these slow-motion scenes because we already know this love to be unlivable, unbearable. The common cannot forever remain in its state of uncommonness and ecstasy.

Wong Kar-wai’s love scenes seem to capture precisely this necessary disappearance: what will survive are the images of love, not love itself—what will remain are fantasies projected onto screens in the cinema or into the hearts of lovers: fantasies that the lovers will live and relive in their minds with the same regularity and redundancy as films themselves are projected endlessly in theatres.

Alain Badiou has once described love as the world experienced from the point of view of two instead of one—love means, first of all, to share. But Badiou seems here to be thinking of one of the few possible and shareable loves that will always have to be found and rescued from an ocean of impossible and unshared ones. Badiou describes what love is, while much love must remain nothing more than a hopeful and painful longing to be. In the Mood for Love doesn’t present us with a shareable love in a shareable world but with a love that is too full, too saturated, indeed, too significant to truly be.

In the Mood for Love is, as the title suggests, precisely about a mood, a Stimmung, that remains tragically out of tune with the world. The dream world of cinema and the dream world of lovers here come together in a hurtful embrace: what remains possible is only the possibility of an impossible dream. What we are left with are only images. Perhaps this is what has haunted me for twenty-five years.

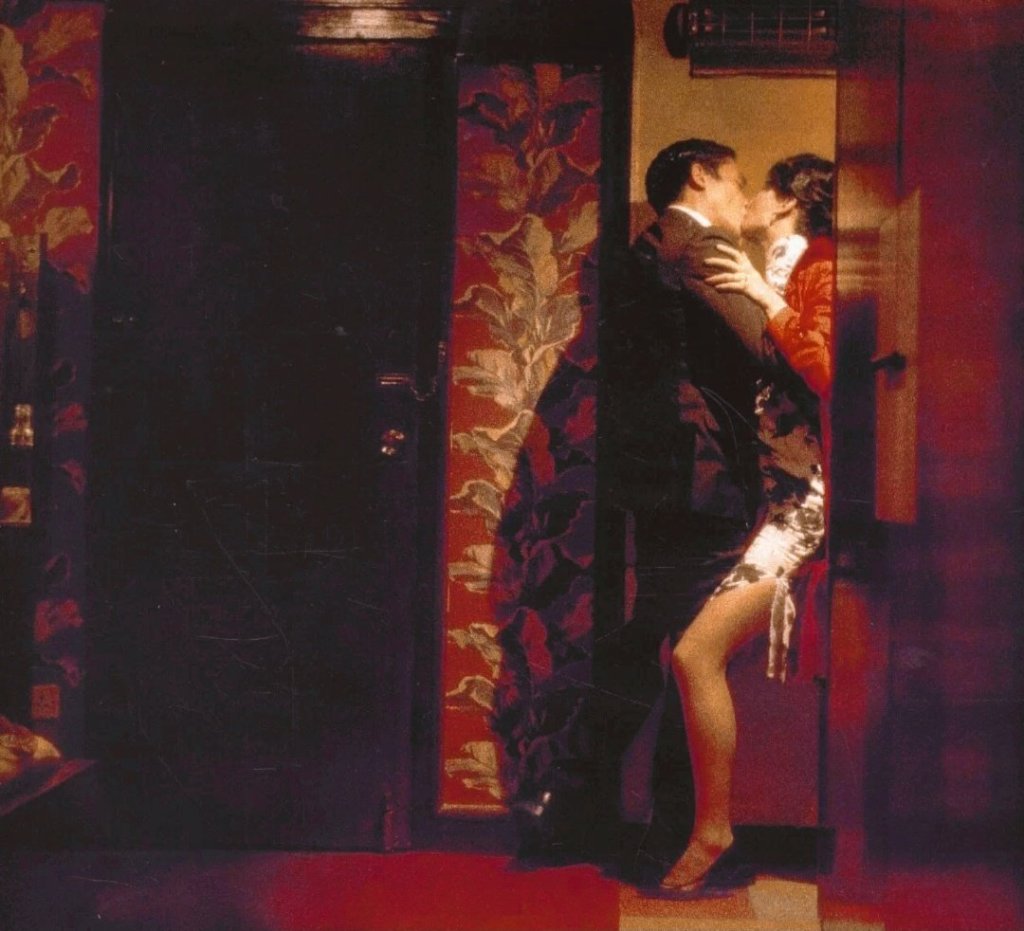

A deleted scene from In the Mood for Love

How to cite: Kølle, Anders. “The Ghosts of Wong Kar-wai: On In the Mood for Love.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 9 Jan. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/01/09/mood-for.

Anders Kølle is lecturer of Communication Arts at Khon Kaen University, Thailand. Holding a PhD in Media and Communications from The European Graduate School, he has taught art and philosophy at several universities, including the University of Copenhagen and Assumption University, Bangkok. His work focuses on contemporary encounters between philosophy and art, and on art’s potential to produce new modes of thinking and create new forms of critique. His publications include On Being Ridiculous (Delere Press, 2024), The Technological Sublime (Delere Press, 2018), and Beyond Reflection (Atropos Press, 2013). [All contributions by Anders Kølle.]