📁RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

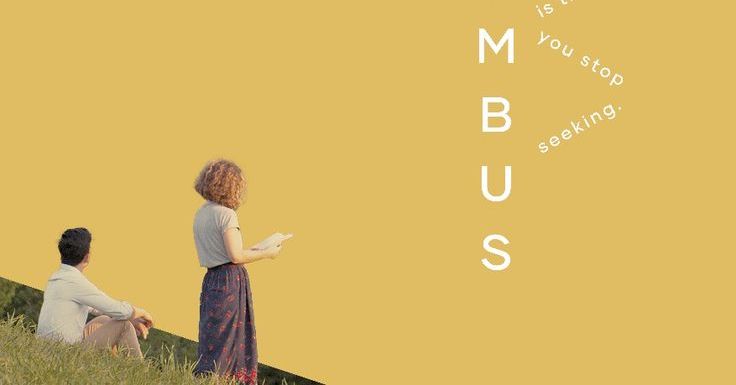

Kogonada (director), Columbus, 2017. 100 min.

There’s a profound sense of openness in Kogonada’s Columbus (2017). The film invites us to step into its scenes, transforming them into spaces where we are not only witnesses but also participants. The very title of the film suggests a journey of exploration, with the town of Columbus itself serving as the central figure—a canvas for the characters, and even the audience, to discover themselves.

I first watched Columbus in 2022 and haven’t rewatched it since. Instead, I’ve allowed the film to linger, letting it resonate as I navigate my own sense of reality. I currently live in a place that feels like the antithesis of Columbus, Ohio. I reside in Mandaluyong, a densely populated city in the Philippines. Its urban compression only intensifies, with a population of 24 million people as of this year.

Metro Manila, of which Mandaluyong is a part, starkly contrasts in its livability. The business districts of Ayala in Makati and Bonifacio Global City in Taguig are upheld as the epitome of a good life, featuring lush parks, walkable streets, and accessible transport—primarily designed for the upper and middle classes. Yet, hidden among these urban landscapes are the overcrowded homes of the urban poor, communities precariously vulnerable to natural disasters that could erase them entirely.

Adding to this sense of disparity is the presence of modern brutalist buildings in the city. I am constantly surrounded by towering skyscrapers, corporate conglomerates, and condominium complexes. Pieces of media such as Playtime! and Severance underscore the grimness of such structures, evoking feelings of entrapment, monotony, and reduction rather than exploration or inspiration.

This is why the subversion of these ideas in Columbus was so comforting. Jin (John Cho) and Casey (Haley Lu Richardson) are able to perceive these structures as sources of groundedness amidst their transient circumstances. The buildings they explore are not merely cold, impersonal forms; they are living entities within the fabric of this modest town: a library, a bank, a school, a firehouse. Casey’s favourite architectural piece in Columbus is a house that once belonged to a couple, a structure she describes with such passion that it becomes a shared moment of connection between her and Jin, framed poignantly behind its glass walls. This setting emphasises the intimacy of their bond, a connection reserved solely for them.

In Jon Wong Ree’s photography book, The Solitude of Human Spaces, he seeks to capture a similar lingering comfort in the places he explored throughout South Korea:

These images of South Korea…imagine people’s unconscious striving to come to terms with their loneliness by facing up to the human condition squarely, steadfastly, serenely.

The concept of liminal spaces has gained significant traction on social media in recent years. Expansive parking lots and abandoned shopping malls have become the focus of a romanticisation of possibility. Yet, despite their vastness, these spaces fail to support a lived existence; instead, they either abandon or invade life due to their temporality and emptiness.

For a space to be considered truly human, it must embody the attributes of human life within its design. Columbus is renowned for this quality in its architecture, seamlessly integrating its small community into a broader vision. As Winston Churchill famously observed, “We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us.”

Walking alongside Jin and Casey, we are invited to settle into each backdrop without interruption, allowing space for reflection. The film encourages us to tune into the sparse yet poignant dialogue between the two central characters and partake in their shared sense of loneliness.

Although I didn’t fully register the names of the buildings while watching, they continue to linger in my memory. One that stands out most vividly is the observatory tower, which Jin and Casey gaze at from a distance. The tower, typically a symbol of observation, is here transformed into an object of observation. It invites us to look beyond ourselves, even if only for a fleeting moment.

The observatory tower stood alone, situated amidst an expanse of grassland that invited us to move freely around it. I later discovered that this was the tower in Mill Race Park—a place once plagued by poverty and hardship, now transformed into a space for communal living and connection.

In Kogonada’s vision of Columbus, we are encouraged to think beyond the physicality of places. The film invites us to imagine possibilities beyond what these structures were originally intended to represent. Jin initially dismisses Casey’s passion for architecture, remarking, “You grow up around something, and it feels like nothing.” Yet, through their interactions, the film reveals our collective capacity to construct meaning—towards a reality where reaching out to one another becomes possible and vital.

How to cite: Clark, V. “Beyond the Physicality of Places: Kogonada’s Columbus.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 11 Dec. 2024, chajournal.blog/2024/12/011/columbus.

V Clark is a researcher and writer based in Mandaluyong, Philippines. Their works have appeared in Sine Liwanag, Novice Magazine, Sinuman Magazine, Kino Punch, and Paraluman: A Sapphic Zine.