📁RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

Benjamin Hegarty, The Made-Up State: Technology, Trans Femininity, and Citizenship in Indonesia, Cornell University Press, 2022. 198 pgs.

I grew up seeing transwomen day and night. During the day, they were at traffic lights, busking with tambourines. At night, they appeared on the television as comic relief. Other Indonesians encountered them in spaces such as hair salons, village festivals, and street corners. While they lived on the margins of society, their presence was seen as normative in Indonesia, the largest Muslim-majority country in the world.

Benjamin Hegarty, a McKenzie Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Melbourne and a Research Fellow at Atma Jaya Catholic University in Jakarta, conducted fieldwork in Indonesia from 2014 to 2015. In his book, Hegarty makes it clear that it focuses on waria, an Indonesian concept distinct from the contemporary understanding of transwomen. According to the book’s summary, warias are part of Indonesia’s trans feminine populations, whose prominence peaked in the late 20th century—ironically during the dictatorship of Suharto.

Hegarty begins by introducing Maya Puspa, an octogenarian at the time of writing, who describes herself as a waria—a term derived from the combination of wanita (woman) and pria (man). In Indonesian cultural understanding, a waria is believed to possess a woman’s soul within a man’s body, which she expresses through dandan—dressing up and applying makeup.

The German sociologist Magnus Hirschfeld coined the term “transvestite” in 1910, and this concept was later applied by Europeans in the East Indies to the local understanding of banci—a Malay term that diminishes masculinity and aligns with colloquial meanings of effeminacy. In the 21st century, Indonesian activists coined the term transpuan as a direct translation of “transwomen,” but Hegarty’s book focuses on waria rather than transpuan.

A Dutch dictionary published in 1942 defines banci as “ambiguity, hermaphrodite, and queen” (in the sense of drag queen). Homosexuality was a capital crime in Batavia (now Jakarta) before 1800, and homosexual relationships between European and Indonesian men caused moral panic in the 1930s. After Indonesia’s independence, nationalists viewed banci as a colonial remnant incompatible with modern Indonesian masculinity. Another moral panic occurred in 1951, coinciding with the arrival of New Look fashion in Indonesia. Banci adopted this fashion, which bewildered nationalist journalists, who argued that no Indonesian man could be homosexual now that the European colonisers had departed.

The Governor of Waria

◯

Sukarno, Indonesia’s founding father, appointed Ali Sadikin as Governor of Jakarta in April 1966. Sadikin later aligned with General Suharto’s regime after the latter overthrew Sukarno. In 1968, Sadikin held a public meeting with twenty-two transwomen who identified as warias. He agreed to act as their patron and coined the term wadam, derived from Hawa (Eve) and Adam. This term invoked a religious framework, both Islamic and Christian, to dignify the community and integrate them into Suharto’s New Order regime.

Indonesian authorities enrolled the wadams in beauty and fashion schools with the aim of turning them into fashion designers, makeup artists, and hairstylists. Sadikin also organised a beauty pageant, titled Queen of Miss Imitation Girls (it’s either Hegarty’s translation or the original name of the pageant), and invited the wadams to perform at the Jakarta Fair. While this policy may seem patronising by modern standards, the wadams preferred this inclusion over the hostility they had experienced under Sukarno’s leadership.

By the 1970s, backlash emerged from religious conservatives, but Sadikin’s influence and popularity shielded his policies from significant opposition. When he retired in 1977, he proudly counted the wadam policy as one of his legacies. Although his successor continued these initiatives, the term wadam fell out of use, replaced by waria, banci, and the more derogatory bencong to describe transwomen.

We Have the Technology

◯

Just as colonial authorities were drawn to Hirschfeld’s theories, Indonesian psychiatrists in the mid-20th century studied the gender frameworks of Robert Stoller and John Money. Several warias arrested by the police became subjects in the University of Indonesia’s Banci Research Project. Magazines attempted to rationalise the waria identity through religious lenses, combining Hindu jiva, Christian psyche, and Islamic ruh.

Vivian Rubianty underwent surgery in Singapore in 1973 and successfully petitioned the Jakarta District Court to change her identity documents. Far from causing controversy, she became a celebrity, received by Suharto himself, and starred in a biopic, I Am Vivian, released in 1977 despite Indonesia’s strict film censorship. At the time, Indonesians prided themselves on their perceived liberalism compared to the Dutch. Even Islamic clerics accepted such surgeries as a way to enforce heteronormativity—a perspective also gaining traction in Iran.

Like Maya Puspa, Vivian Rubianty was Christian and ethnically Chinese, factors that made her more acceptable to the Indonesian public as a “model minority”. She explicitly rejected the label banci, identifying only as a woman. Netty Irawati became the first Indonesian to undergo gender-affirming surgery domestically in 1975. This milestone was celebrated, although by 1978, the Department of Health concluded that surgery was not a long-term solution. Nevertheless, state hospitals continued to perform surgeries, mostly for intersex cases, until 1989.

National Glamour

◯

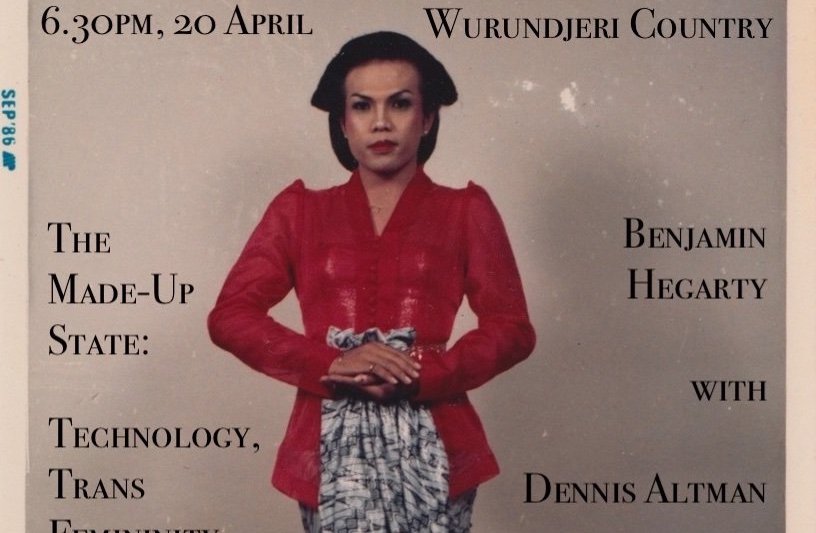

Although Suharto turned to stronger conservatism in the 1980s following the Iranian revolution and the Anglo-American conservative resurgence, the warias were very much integrated into the Indonesian society. They became the stylists and confidants to prominent women, performed at state-sponsored events, and even served as spokespersons for government initiatives. The front cover of Hegarty’s book features Yetti, a waria from Yogyakarta who performed and presumably gave a speech at a Planned Parenthood Association event in 1986.

Hegarty omits the stories of celebrity warias such as Ade Juwita, Tessy, and Karjo AC-DC from the Srimulat comedy troupe, and Dorce Gamalama, who starred in her own films in 1989 and 1990 (preceding anything in Hollywood and Hong Kong); she became a top-rate host, hailed as “Indonesia’s Oprah” in the 2000s. Perhaps it would be harder to approach their circles and to categorise these performers, especially those who didn’t identify themselves as warias, and maybe personally Hegarty wanted to focus on ordinary people.

The final chapter of The Made-Up State explores Tadi’s photo archive, who archived pictures of herself and other warias in magazine quality dresses, makeups, and sets. Hegarty explains the initiation stage of a waria, from ngondek (wig/feminine) curiosity, to practising the arts of dressing up and applying makeups as a banci kaleng (canned/fake gay), to socialising with other warias that includes the nyebong sex, to finally the made-up stage of dandan, when the person has become a part of the community.

The “gay” concept arrived in Indonesia in the 1980s, although obviously gay Indonesian men who didn’t dress as women had been around. The death of Freddie Mercury in 1991 sent a shockwave in Indonesia as many Indonesians saw him as a symbol of masculinity and even mistook him as a Muslim. Boy George, meanwhile, was also well-accepted in Indonesia and became a role model for Indonesian warias of the 1980s. Like elsewhere, by the 1990s white collar gay men were accepted in professional settings as long they kept their identity discreet and apolitical, just like the warias were accepted in the restricted settings of beauty salons and theatres.

The Generational Divide

◯

The 21st century has brought new challenges for Indonesia’s LGBT+ communities. The Pornography Law, passed in 2008, has been used to indict even victims of leaked sex tapes, while online pornography remains widespread. By 2016, when Hegarty concluded his research, mainstream Indonesian media were united in opposing LGBT+ rights, even as alternative online platforms amplified LGBT+ voices.

Hegarty refers to transwomen throughout as warias because older warias reject the term transpuan (transwomen), considering it overly political and erasing the male aspect of their identity. He also notes the political nuance between wanita and perempuan, with the latter now preferred as a progressive term to counter Suharto-era patriarchy.

Throughout this review and the book, the transwomen have been referred as warias for a reason. Hegarty says that older warias disagreed with the newer term of transpuan (trans + perempuan, transwomen), since they believed it was a political term that would not convince the public and erased the male aspect of their person. He also explains the political nature of the two words for a woman, wanita and perempuan. The former had been called a sexist word by feminists since the 1990s, akin to how English-speaking feminists view the word “female”. Perempuan is now the word used in formal and everyday contexts, both as a respectful way to address women and to break away from Suharto’s patriarchal legacy.

Hegarty does not cover the transpuan perspective because he says their voices are still confined to social media, as is the case in other societies in Asia and the wider world. An Indonesian active on Instagram and X might follow some transpuans and the word is familiar for a newspaper subscriber, but they are invisible outside their networks. There are no more transwomen busking on the traffic light and no more popular trans comedians and drag queens. Like elsewhere, the new generation of transpuan writers and artists have stronger political opinions online, have more cosmopolitan outlooks and experiences, and are more sceptical of the government compared to their waria elders.

This book is best to be understood as a history of trans femininity in Indonesia in the 20th century. Ironically, the authoritarian Suharto era was the golden era for the warias, who were co-opted and appreciated by the state. The Made-Up State explains well how this was done and how the warias negotiated their personal identity, citizenship, and public acceptance despite the odds. Hopefully a new level of coexistence and tolerance in Indonesia can be reached in the short future.

How to cite: Rustan, Mario. “Dress Up for Indonesia: Benjamin Hegarty’s The Made-Up State.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 29 Nov. 2024, chajournal.blog/2024/11/29/make-up-state.

Mario Rustan is a writer and reviewer living in Bandung, Indonesia. [All contributions by Mario Rustan.]