TIFF 2024

▞ Introduction

▞ 8. Band of Outsiders: On Neo Sora’s Happyend

▞ 7. The Soul of an Artist: On Hong Sang-soo’s By The Stream

▞ 6. The Two Maidens: On Trương Minh Quý’s Viet and Nam

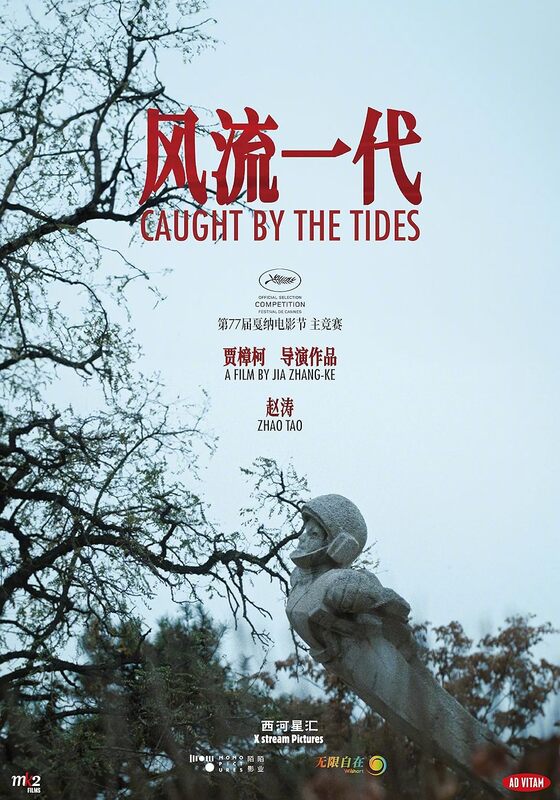

▞ 5. The Master and Her Muse: On Jia Zhang-ke’s Caught by the Tides

▞ 4. Self-Studies: On Sook-Yin Lee’s Paying for It

▞ 3. The Inheritance: On All Shall Be Well and The Paradise of Thorns

▞ 2. A World of Pain: On Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Cloud

▞ 1. Mise en abyme: On Lou Ye’s An Unfinished Film

Jia Zhang-ke (director), Caught by the Tides, 2024. 111 min.

At the turn of the century, she walks onto the stage wearing a stiff blue uniform, her hair in pigtails. She stops a little bit off centre and turns to address the theatre’s audience—an emcee, she is, a chorus of one, a siren, a lover for our modern times.

There’s something about the actress Zhao Tao—something subtle, enigmatic, elusive—that captivates us whenever she’s on screen, since she never says much, opting rather to emote and embody her feelings. We can’t help but observe her—its like trying to interpret an enigma; a sphinx—so we cultivate, in Bertolt Brecht’s words, a “watching attitude” towards her.

In Platform (2000), for instance, her first acting role, we watch as she watches a Bollywood film with her lover, and smokes for the very first time with a friend, or we yearn to see more of her after she disappears behind a brick wall, and to hear her sing about what a romance, a ballad is.

A subtle performer like Zhao does away with guiding the audience overtly as an unknown, an alien, a labyrinthine, a cipher of information that taunts and propels the narrative through her sheer presence; and if she is as skilled as the hand of its master, she becomes the site of narrative itself.

“I act to what I think the character should be,” Zhao said in a MUBI interview with Darren Hughes: “I didn’t choose to be an actress. The career chose me.”

In the 24 years since Platform’s release, it seems with each successive film Jia Zhang-ke and Zhao Tao—husband and wife in real life— collaborate on, they seem to have been actively pursuing the limits of what the seventh art can be. To consider Zhao Tao’s career, then, is to regard, to pay close attention to the ways the colour of a flower deepens, with no sign of deterioration overtime, of an essence that does not fade, that perpetually reinvigorates itself.

But their newest film, Caught by the Tides, does not begin with Zhao: instead, we encounter a man standing next to a fire holding a wrench; followed by several women taking turns singing.

To go into any film with expectations is to contend with your frustration, I thought: but when she finally does appear—wearing a bob-length wig—it is with such force that you can’t help but grin in recognition of a woman who feels familiar and yet will forever remain foreign to us.

Zhao Tao’s character Qiao Qiao dancing for a crowd with a feigned smile on her face

We see Zhao’s character Qiao Qiao dancing for a crowd with a feigned smile on her face.

Later, when she is in a night club, dancing on her own, that smile—no longer required to convince anyone of her joy—is nowhere to be seen.

In the second chapter, when she has a miscommunication with the food vendor on the boat, Zhao—in that iconic yellow blouse from Still Life (2006), still holding onto that blue-capped water bottle—smiles in response to her hasty oversight, her ignorance.

That smile is repeated when a man—who appears out of the blue in the rain—takes it upon himself to do a reading of her face, divining that she will be healthy and happy. But then her face inverts itself and becomes a cry from deep within the soul and then he, too, falls silent.

et as the film goes on, this narrative arc of Zhao Tao’s smile does not relent; in fact, it continues, as though the whole film has been shaped around this refrain: in the third and final chapter of the film—the only that was filmed for this film and set during the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic—as Qiao Qiao leaves the grocery store where she works as a cashier, she runs into a robot. It, too, wants to recognise her face: but she has to take of her mask first.

“You look sad,” the robot finally declares.

You cannot hide the truth, her face seems to say: even from Artificial intelligence.

Caught by the Tides is both an experiment and an exercise: based on an abandoned film Jia found sifting through his archive—which he’d called “The Person Who Held the Digital Camera”—and finding a semblance of a shape within it: these sections are when the film is vibrant, alive, active—before, in the film’s third act, it goes for coherence, it is made up of intentions rather than accidents made intentional, losing hold on the punk-like spirit with which it starts.

It ages before your eyes: in form, and in content.

In the first chapter—which takes place in 2001—Qiao Qiao is observed by all those around her: whether it’s the patrons at the bar, or the potential clients in the mall where she models, or in the streets as she’s catcalled by motorcyclists; but in the second chapter—which takes place in 2006—she occupies the space of the observer, relentlessly searching around the Three Gorges Dam area for her old lover, studying the locals and the landscape, running into dead ends.

“What should I do,” she texts him: but he never responds.

In both these sections, too, there is a hint of violence, as when Qiao Qiao goes round the room trying to swat down a fly—she never gets it—or when, instead of the money in the envelope that she is accused of stealing, she pulls out a Taser to fend off the assailants.

Entrapment as a central theme it is never more apparent than in the 2001 section, as she tries repeatedly to leave the bus, but Brother Bin, played by Li Zhubin, keeps stopping her, pushing her back onto her seat. She starts weeping, tries again, takes off her wig, tries again, and again, and finally, costume in hand, she manages to escape, physically, while that mental state which, as in the last chapter, seems to still be with her throughout the years.

Her wound is exposed to us when, while weighing a vegetable in the supermarket, she looks up and sees him—instantly recognising him—and her eyes ever so slightly widen. She manages to express herself beyond the mask in a way only a human being can understand.

If a face can launch a thousand ships, Zhao Tao’s suggests that they can be the foundation of a thousand films too.

In a sense, in Caught by the Tides, Zhao acts as a series of rocks along a stream where, from time to time, we rest for a bit before moving to the next stop, garnering enough information to have a through-line that gives the film enough support to feel whole.

But between these “Zhao Stops” we are suspended in a transitional space, drawn on by the current of the procession of time—and this is where Jia allows his cultural, political and anthropological impulses to come through, for his mastery to shine: whether it’s a tracking shot of the streets of a Northern Chinese city; a man explaining why he keeps a burnt portrait of Mao; the destruction of infrastructure along the Yangtze; a collage of some of the 1.16 million people displaced by the rising water levels around the Three Gorges; the passengers on the plane heading to Datong exchanging their WeChat information; the way that people make a living on Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok; or the subplot of a queer man who never lives his life openly.

Along with the archival footage that the film makes use of—or the situation that Zhao’s character finds herself in—all of this is “caught by the tides” of the singular vision of its director, who, in the film’s first two chapters, exhibits a sort of freedom and curiosity about the world that is rare to witness these days, insatiable as he is to take in the world around him, to try out different forms, constantly changing the aspect ratio, abstracting the images and superimposing them, to an electrifyingly score by Lim Giong (Millennium Mambo).

At the end of Caught by the Tides, Qiao Qiao takes off her mask, flips over her vest, slips lights around her arms, and turns on the lights on her shoes. She doesn’t so much as bid farewell to Brother Bin as slip out of his orbit and fall into line with the mass of runners moving through the streets. She falls in the centre, where she, who has been mute throughout the film, lets out a fierce empathic shout, one that ushers in a new era, one in which the self is a crowd.

“Yup,” Zhao Tao has said of Qiao Qiao: “That’s me.”

How to cite: Nagendrarajah, Nirris. “The Master and Her Muse: On Jia Zhang-ke’s Caught by the Tides.” by Nirris Nagendrarajah.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 29 Oct. 2024, chajournal.blog/2024/10/29/tides.

Nirris Nagendrarajah (he/him) is a Toronto-based writer whose work has appeared in paloma, Polyester, Fête Chinoise, In the Mood Magazine, Tamil Culture, in addition to Substack. He is currently at work on a novel about waiting. [All contributions by Nirris Nagendrarajah.]