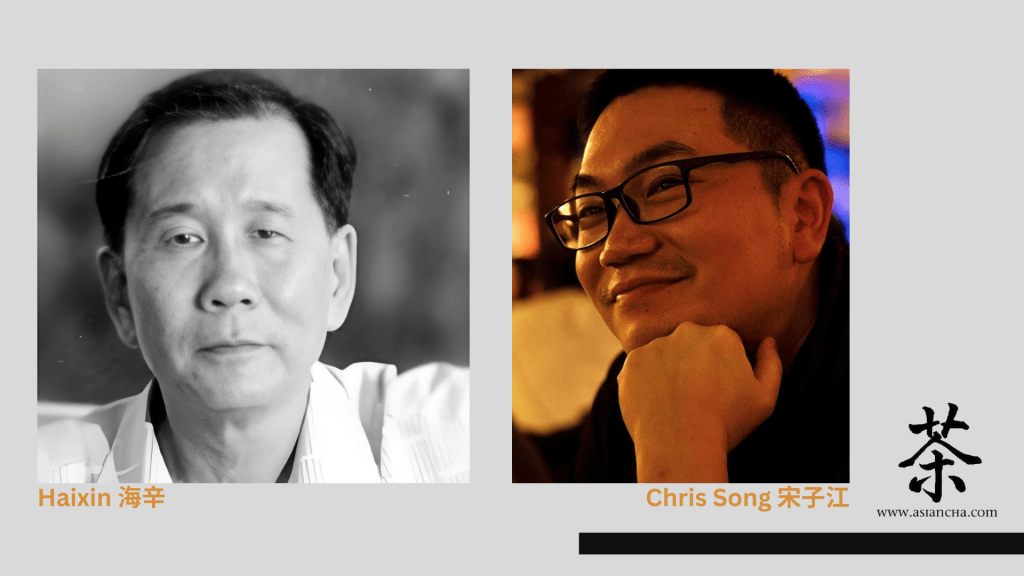

Chris Song’s note: Haixin 海辛 (1930–2011) was one of Hong Kong’s most prolific realist fiction writers. His deep curiosity about various professions and the lives of ordinary people in Hong Kong, combined with his broad taste in literature, allowed him to transcend the limitations of leftist ideology. Throughout his writing career, Haixin used unadorned language to vividly depict the everyday experiences of Hong Kong people. His fiction is characterised by a strong social conscience infused with his own emotions and ideas, creating a powerful resonance that deeply moves readers.

The emotional complexity in “Spirits of Cicadas” 蟬魂 highlights the internal conflicts faced by individuals navigating love, obligation, and greed. The use of the supernatural—cicada spirits taking revenge—adds a layer of poetic justice, emphasizing the consequences of one’s actions. This blend of realism and allegory underscores Haixin’s ability to evoke empathy while also critiquing the social dynamics and moral choices of his characters.

She woke up at around seven in the morning, as usual. But today was different—she wasn’t roused by the summer chorus of “buzzing” cicadas. Every morning, without fail, it had always been their song that woke her.

She turned over and looked at the other side of the bed, where the pillow lay empty and the sheets untouched. She was used to it by now.

With a derisive snort, she muttered, “Off to that real estate agent so early again? Or maybe he’s arranged a tryst with that vixen, driving up to the hills for a little fun before pretending to get on with his so-called real business.”

She hurriedly got out of bed, threw on her white robe, and pushed open the sliding glass doors that separated the cool air-conditioned room from the balcony. A warm but fresh draft rushed towards her, enveloping her face.

Yet still, she couldn’t hear the cicadas.

On the grass under several green trees, she saw Yau-hing, who had come to the villa a few days ago, supposedly to help out instead of her ailing father. He was strong and healthy, wearing a white tank top and blue shorts. He held a rectangular cardboard box, bending down again and again, carefully picking up—from the grass beneath the trees—the bodies of dead cicadas.

She felt a mix of shock and anger, shouting at him, shouting, “So it was you who killed my cicadas!”

Yau-hing didn’t say a word. His expression remained solemn as he continued gathering the cicadas, their transparent wings blackened, now lying lifeless on the green grass.

She spun like a whirlwind, rushing from the second floor to the grass below, her heart aching as she picked up one of the dead cicadas.

“Too cruel,” she said, her voice trembling. “You couldn’t have me, so you pretended to cover your sick father’s gardening shift, all just to kill my beloved cicadas.”

Yau-hing looked at her briefly, his face cold and disdainful, before bending down again to continue collecting the cicada corpses. She moved closer, raising her hand as if to slap him.

Before she could, Majo, the Filipina domestic helper, came out from the house, raising her voice, “Madam, don’t blame him. Last night, Mr. Kiu climbed up the trees himself, one by one, spraying insecticide on the cicadas. Look—”

Majo pointed to the distance, where, under an olive tree, lay the discarded insecticide can and sprayer.

In an instant, her heart swelled with guilt, her face flushed with regret. “Yau-hing, I’m so sorry,” she whispered.

But he said nothing, continuing to pick up the cicada bodies, one by one.

The villa stood at the far end of Mount Davis, facing the ocean, with a view stretching to Dumbbell Island and the slopes of Lamma Island. It had sprawling lawns and gardens, and from here, one could watch the sun dip below the horizon. The surroundings were almost painfully beautiful.

It was called “Cicada Mansion.”

But she was not named after cicadas. Her name was Cha (meaning tea). Even before the villa’s mistress adopted her, she had been called Tea, just another child in the woods below Mount Davis. Back then, her surname was Yip (meaning leaf), and among the families scattered through the forested hills, they called her “Tea Leaf”.

At thirteen, she was adopted by the villa’s mistress, a Frenchwoman named Mylène Cigales, the lover of the Hong Kong real estate tycoon Mo Chun-kit. He had brought Mylène here from Paris, but of course, she couldn’t be allowed into the crowded, gossip-obsessed Mo family residence on Blue Pool Road. So, a place was set up for her—this villa on the slopes of Mount Davis, far from the main house.

Before becoming the daughter of “Cicada Mansion”, Tea had lived in a wooden house in the hills with her parents, who carved headstones for the cemetery nearby. She had an older brother and a younger sister.

In the summer of her twelfth year, Tea often went with Yau-hing, the boy from the neighbouring house, to catch cicadas. In those days, children in the streets of Western District would pay to buy cicadas. She and Yau-hing would catch them—well, it was mostly Yau-hing climbing the trees while she waited below, watching him move among the branches.

One day, Yau-hing and Tea discovered that the trees in Cicada Mansion, by the sea and halfway up the mountain, were teeming with cicadas. As soon as the golden sun rose, the air would fill with a “buzzing” chorus, a net of sound that enveloped anyone standing nearby.

Yau-hing was convinced that sneaking into the garden to catch cicadas would be worth it. After all, his father was the head gardener of the villa, responsible for the lawns and the swimming pool. Using that connection, Yau-hing quietly led her down the stone steps to the rocky shore. They stripped off their outer clothes, leaving only their underwear, and swam together. Yau-hing carried a long bamboo pole, its tip smeared with adhesive, while Tea brought a woven bamboo basket and a tube of glue. They swam to the rocky shore below Cicada Mansion, climbed up, and quickly made their way to the garden lawn.

Like a tree frog, Yau-hing climbed up a tree that was teeming with cicadas, his bamboo pole in hand, the basket hanging from his side.

Finally, there came a time when they were intercepted. Mylène, who had been hiding behind a fake rock hill, blocked their escape to the stone steps. Uncle Pung, the gardener, caught Yau-hing by the back of his collar, holding him immobile.

Uncle Pung snapped the bamboo pole in two and was about to strike Yau-hing when Mylène intervened. She pulled out two red banknotes and said, “Yau-hing, I love cicadas, and I don’t want anyone hurting them. Take this money, and from now on, don’t sneak in here to catch them for sale.”

Yau-hing glanced at Uncle Pung, who scowled and said, “Well, aren’t you going to thank Miss Mylène Cigales? Apologise!”

Yau-hing accepted the two hundred-dollar bills, handing one to Tea. They both knelt down, thanking Mylène and pleading for her forgiveness.

But Mylène wouldn’t let them kneel. Instead, she invited them to join her birthday party that day, her eyes alight with interest.

The whole afternoon passed, and Mo Chun-kit, the man Mylène had been waiting for, never showed up. Disappointed, she turned her attention to Tea and Yau-hing, treating them as her guests, playing games with them, laughing.

That Christmas, Mylène came to Tea’s house, speaking with her parents about adopting her. She offered them one hundred thousand dollars.

Tea was even happier than her parents, who accepted the money. From that day on, she lived at “Cicada Mansion”, calling Mylène “Mommy.” She was now the young mistress of the beautiful villa.

When she was eighteen, during a scorching summer, Mylène returned to France, leaving Tea alone in “Cicada Mansion” with only a part-time local maid who worked during the day and went home in the evenings.

It so happened that Uncle Pung, the gardener, injured his leg and went home to recover, leaving Yau-hing, now twenty-one, to take over his duties. Yau-hing had just graduated from college and was looking for a summer job, so he came to replace his father for a while.

It was just Tea and Yau-hing, alone together—a time of youthful joy, the happiest days of her life.

Every night, Yau-hing would keep Tea company on the second floor until midnight, then head downstairs, crossing the lawn to sleep in the stone house.

One sleepless night, Tea found herself tormented by the romantic scenes from a movie they had just watched, tossing and turning in bed. She asked herself, “Tea, do you love Yau-hing?”

She answered herself, “If I didn’t love him, I wouldn’t be spending all this time with him.”

A voice inside encouraged her: “If you love him, be brave, like the heroine in Love Across the Strait, and go to him.”

So she put on her robe and stepped out of her room, turning on the lights as she went downstairs. She pushed open the aluminium-framed glass door. Oddly, as she stepped barefoot onto the lawn—

Chirp, chirp, chirp—

The night cicadas sang from the trees, their song piercing the darkness.

Yau-hing, in his tank top and underwear, was drawn by their night-time song as well, appearing in the light of the stone house doorway.

They ran across the lawn together, meeting beneath a palm tree, collapsing onto the grass in each other’s arms.

“Why are the cicadas singing so late at night?” she asked.

He whispered into her ear, “They’re singing a love song for us.”

Wrapped in his embrace, she said, “How poetic, how romantic. If they’re singing a love song for us, we shan’t be shy.”

And there, under the starlit sky, they gave themselves to each other for the first time.

He laughed softly afterward, “Do you know why the cicadas are singing so loudly for us, even at midnight?”

She stared at him in the darkness. “I thought you said it was their love song for us,” she replied, still savouring the moments they had just shared.

He grinned. “It’s because you turned on the lights upstairs, then came down and turned on more lights. When you stepped out onto the lawn, the cicadas thought it was morning, so they started to sing.”

She playfully slapped him. “You tricked me, made me think they were singing for us!”

He pulled her close again, his arms wrapping around her. “Let’s always remember this night,” he said. “The night the cicadas sang their love song for us.”

Tea was twenty-five now, the rightful inheritor of Cicada Mansion.

Mylène had been seriously injured in a car accident and lay in a hospital bed. She spoke to her lawyer, willing her savings and bank deposits to her illegitimate son in France, while the villa—Cicada Mansion—she left to her adopted daughter, Tea.

She had one request: that Tea marry Kiu Shing, the son of her best friend in Hong Kong, Kiu Wing-sun.

After the funeral, Tea took Mylène’s ashes to Paris with Shing by her side. In their hotel room, she remembered her mother’s final wish and offered herself to Shing. Though it was her second time, Shing didn’t mind.

This man, who ran a real estate company, cared mostly about the seaside villa she owned. By his estimate, Cicada Mansion, with its vast lawns and prime location, covered over twenty thousand square feet. If it were redeveloped into luxury condos, he and Tea could become fabulously wealthy.

After they married, Tea continued to manage the flower shop in Central. With two female employees to help, it required little of her energy.

She felt the most guilt for betraying Yau-hing’s love. But Yau-hing understood her situation—how she had to follow her adoptive mother’s wishes and marry Shing to keep Cicada Mansion. He never blamed her.

With her encouragement, Yau-hing, who had become a supervisor at a public garden, married her younger sister, Siu-ling. It was, in a way, a form of compensation.

But the marriage wasn’t harmonious, and two years later, they divorced without children.

As Tea, the older sister, could only sigh and say, “Yau-hing and I had fate but no destiny, while my sister and he had destiny but no fate.”

She thought she could bury her emotions and build a good life with Shing. But being a good couple wasn’t as easy as she had imagined.

Shing was a philanderer. None of the three female employees at his real estate office had escaped his advances. He also maintained a close relationship with a female boss from another property company, exchanging information over drinks and booking hotel rooms under the guise of business discussions.

Recently, Shing had brought Liu Jin, a major real estate mogul from China, to see Cicada Mansion. The wealthy businessman fell in love with the place immediately and offered fifty million for the land to build luxury apartments.

No matter what, Tea refused to sell. A thousand words, ten thousand reasons—still, she shook her head.

It all came to a head one night after a terrible argument. Shing was convinced the cicadas were the reason she wouldn’t sell the villa, that they held her back from making a fortune. And so, last night, he decided to exterminate them all, killing every cicada in the garden’s trees.

“How foolish,” Yau-hing said. “He wiped out the cicadas in the garden, but come morning, won’t others just fly in?”

She sighed. “Maybe one day, Shing will come for me too.”

Now, Yau-hing had gathered all the cicada bodies from the lawn and was walking quickly toward the stone house to fetch a shovel. He returned to the grass, digging a hole.

She knew what he intended but still asked, “Are you burying the cicadas?”

He paused, looking up at her. “You don’t mind, do you?”

She gave him a glance full of gratitude. “How could I mind?”

Just as he finished burying the cicadas in a cardboard box, a traffic policeman arrived at the door on a bicycle.

“Your husband, Mr Kiu Shing, was driving down the mountain this morning when he was attacked by a swarm of cicadas,” the officer said.

Tea interrupted in surprise, “Cicadas aren’t aggressive.”

The officer nodded. “Exactly. But this swarm was fierce. They flew into the car, attacking his eyes, ears, mouth, and nose. He tried to swat them away, lost control of the car, and it went over the cliff. I’m sorry, ma’am—Mr Kiu didn’t survive.”

Tea didn’t feel sadness. Instead, she said, “He killed the cicadas last night, and their spirits took revenge this morning. Who knew that even the smallest of cicadas could bring down their enemy?”

Around one in the morning, Tea found herself sleepless. She couldn’t lock away the grief of widowhood, couldn’t quiet her body’s desires. She turned on the lights in the living room, opened the aluminium door, and stepped out onto the grass.

Chirp, chirp, chirp—the cicadas were singing again.

She wondered—were they the spirits of the dead cicadas, or had new ones flown in from elsewhere?

At the far end of the lawn, the stone house was lit up. The door was open, and there stood Youxing. Unlike last time, he didn’t step out onto the lawn to meet her. He stood there, still.

She walked quickly to the doorway, reaching out and pulling him closer. “Yau-hing, are you still mad at me?”

He looked at her. “Why would I be mad?”

“Mad because I thought you killed the cicadas.”

“It’s all clear now. The one who killed them got his comeuppance. Why would I still be angry?”

“Do you still love me?”

He listened for a moment. “Hear that? The cicadas are singing a love song for us again.”

Encouraged by his words, she shrugged off her robe, letting it fall, and threw herself into his arms, his tank top and shorts soft against her skin.

“Do you think it’s the spirits of the cicadas singing for us?” she asked.

He held her tightly. “I buried them this morning. And now, at midnight, they’re singing for us again.”

“Why not say they’re new cicadas, drawn by the light, thinking it’s dawn?”

“I’d rather it be their spirits.”

“Why?”

“Cicada spirits repay their grudges, and they also celebrate the good. Now, with you and me together, they’ve forgotten their grievances and are singing for us tonight. By tomorrow, Cicada Mansion will be alive with cicadas again.”

How to cite: Song, Chris and Haixin. “Spirits of Cicadas.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 26 Oct. 2024, chajournal.blog/2024/10/26/cicadas.

Haixin 海辛 (1930–2011) was one of Hong Kong’s most prolific realist fiction writers. His deep curiosity about various professions and the lives of ordinary people in Hong Kong, combined with his broad taste in literature, allowed him to transcend the limitations of leftist ideology. Throughout his writing career, Haixin used unadorned language to vividly depict the everyday experiences of Hong Kong people. His fiction is characterised by a strong social conscience infused with his own emotions and ideas, creating a powerful resonance that deeply moves readers.

Chris Song (translator) is a poet, editor, and translator from Hong Kong, and is an assistant professor in English and Chinese translation at the University of Toronto Scarborough. He won the “Extraordinary Mention” of the 2013 Nosside International Poetry Prize in Italy and the Award for Young Artist (Literary Arts) of the 2017 Hong Kong Arts Development Awards. In 2019, he won the 5th Haizi Poetry Award. He is a founding councilor of the Hong Kong Poetry Festival Foundation, executive director of the International Poetry Nights in Hong Kong, and editor-in-chief of Voice & Verse Poetry Magazine. He also serves as an advisor to various literary organisations. [Hong Kong Fiction in Translation.]