📁RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

Click HERE to read all entries in Cha on Natsume Sōseki.

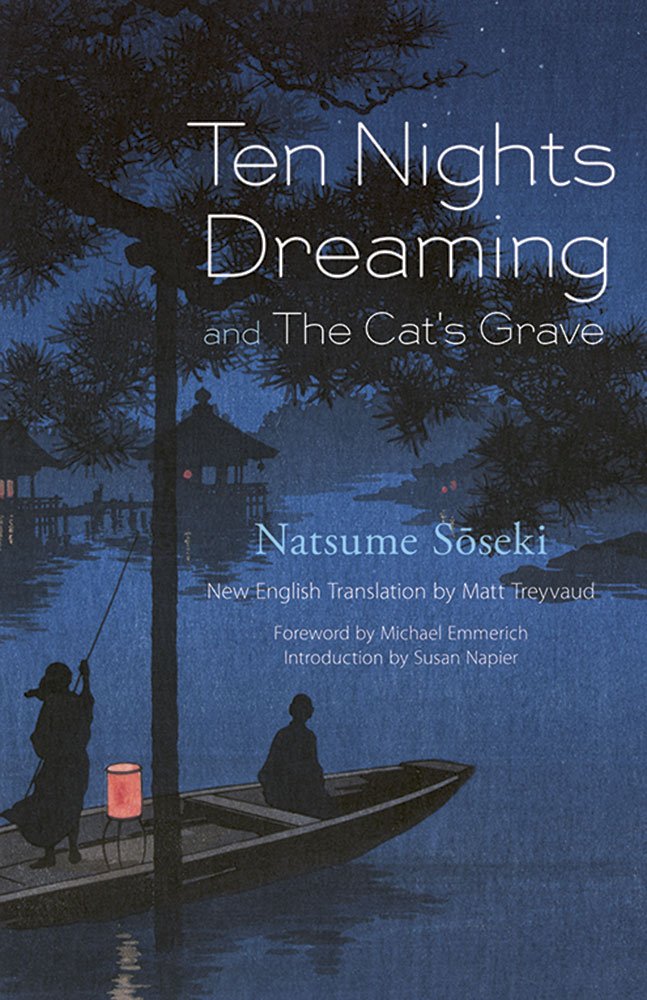

Natsume Sōseki (author), Matt Treyvaud (translator), Ten Nights Dreaming and The Cat’s Grave, Dover Publications, 2015. 96 pgs.

Natsume Sōseki’s Ten Nights Dreaming is a book I’ve returned to again and again. I first encountered this work in the mid-1970s, in a battered Tuttle translation I rescued from a bin pile, so ragged and thumbed through I could scarcely believe that it had been recently published. I have no idea how it came to be in such a state. I began to read it there and then, and knew I had to take it home with me.

Each return to this book has resulted in multiple readings. From my first encounter with the 1974 translation by Aiko Ito and Graeme Wilson, then a 2000 translation by Lovetta R. Lorenz and Takumi Kashima, and finally a 2022 translation by Sankichi Hata and Dofu Shirai, I have continued to love this book. But it is Matt Treyvaud’s 2015 translation, of the four English translations I have read, that is my favourite.

Treyvaud’s introduction to his translation includes brief explanatory notes, and helpful links to his source texts, both online and in print. The impressive Michael Emmerich has written the foreword, and the equally impressive Susan Joliffe Napier has an engaging introduction. While not discussed here, this translation also includes “Our Cat’s Grave,” a short autobiographical story often aligned with Sōseki’s popular novel, I Am a Cat.

What stands out for me in Treyvaud’s translation is his attention to Sōseki’s modernism, his shifts in narrative voice and style. This has resulted in an overall mysteriously translucent sequence of stories, variable, but fluid, perhaps even connected (as “The Eighth Night” and “Tenth Night” seem to be) but not quite in focus. It is indeed a dreamlike book.

“The First Night” dream acts as a portal, through which one glimpses the otherworldly to come. A beautiful woman is dying, and the narrator is there, loves her, is at first incredulous, then solicitous. The woman does die, after she extracts a promise. If it is kept, she vows to return. This promise defies reason, but not love, or grief, or dreams. Will her lover wait for her, beside a grave marked by a fragment of a falling star, and if he does, will she return? The dialogue here is straightforward. One might recognise the origin of such language, especially those who have spoken with the terminally ill. Yet one cannot know what lies beyond such a conversation. That is where the dream reigns.

“The Second Night”’s narrator is a significant shift from the first night’s lover. He is a samurai, inordinately proud, haplessly idealistic, spiritually blind. Zen practice has for him become aspirational, competitive, a series of well-managed disciplinary processes, with an outcome that is absurdly binary. Treyvaud’s translation of the narrative voice rings true and makes the warrior’s self-delusion clear.

“The Third Night” narrative shifts again, this time to a boy carried along a path on the back of a man, unseen, whom he converses with, and calls father. The boy’s knowledge of the path, and what lies ahead, is anything but innocent. We, like the man, are troubled deeply by the boy. Is he mad, or evil? Is he even, really, a child? There is blindness in this story too, but it is far more malignant, and damning, than we realise. While we sense it as readers, the awful end of this tale remains shocking and unexpected.

“The Fourth Night” records a recollection of a boy, as an adult. The story begins with a conversation between a restaurant proprietress and a very old man. They are observed by a curious little boy, who is infatuated with the old man’s trickster retorts and claims to be able to conjure a snake. Again, the narrative aura has shifted, and we are left with an unexpected end, but one that is more mysterious than terrifying.

With“The Fifth Night”, the book swerves, the narration now that of a professional storyteller. Here Japanese myth and ancient history blur together to recount for us a tale of thwarted love. There is no falling star, no light for lovers, as in The First Night, but an end as deep as a chasm and as unpitying as it is malicious. The narration ends with the storyteller shifting voice to speak to the reader directly. “The Sixth Night”blends medieval and modern history. The narrator is not a professional storyteller but a curious Meiji-era citizen, visiting a temple to watch the great medieval Buddhist sculptor Unkei work. Why has Unkei returned? How does he carve? The narrator represents both the optimism and deficits of modern Meiji sensibilities, a lesson that holds truth for our era as well. Treyvaud captures in English the casual unflattering ignorance that can surround an artist at work.

“The Ninth Night“ once again explores love, hope, and grief. The number one hundred returns, a kind of touchstone of devotion. Yet the narrative simply assures us such devotion will remain futile, suggesting that death may have preceded supplication. There is something prescient, Camusian, in the widow’s nightly ritual.

The three remaining stories remain within the Meiji period when Sōseki lived and wrote.

“The Seventh Night” begins at night on the deck of a coal-fired steamer, loud, dirty, heading west. The passengers—mostly foreigners—and a Japanese narrator are lonely, disconnected, even desperate, as isolated as the ship they find themselves on. The narrative deftly presents the alienation so prevalent in the modern world. The ship of progress or fools? This dream is awash in despair.

“The Eighth Night” and the final “Tenth Night”veer away from this darkness. These dreams land us in brightly lit landscapes, contemporary, humorous, and magical, and highlight a tolerance for human imperfection.

There are portals in “The Eighth Night”too, echoing the first dream, but here they are mirrors in a popular, gossipy barber shop, where one feels connected to others, and to one’s surroundings. We meet Shōtaro, a comical character in a much-admired Panama hat, who reappears in “The Tenth Dream”. Sōseki’s fondness for contemporary Japanese comic storytelling, Rakugo, is apparent. Again, Treyvaud does a marvellous job of imbuing the English translation with the spirit of this performative style.

Rakugo, by the way, remains popular. A modern storyteller, performing in English, can be viewed here.

Sōseki chose to end his book of dreams here, in sunlight, on the streets he knew, where the familiar and the strange seem to exchange pleasantries, wink at one another, and us.

How to cite: McDonald, Marsha. “A Dreamlike Book: Natsume Sōseki’s Ten Nights Dreaming and The Cat’s Grave.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 20 Jun. 2024, chajournal.blog/2024/06/20/ten-nights-dreaming.

Marsha McDonald lives in Vilar de Andorinho, Portugal. An artist and writer, she works and exhibits between North America, Europe, and Asia. She has received grants from the Pollock-Krasner, Puffin, Mary Nohl (travel), Lynden Sculpture Garden, Gallery 224 Artservancy (artist working within conserved land in Wisconsin USA), and a New York Fellowship. Her writing has appeared in Otoliths (Australia), The Drum and The Cantabrigian (Cambridge MA), Voice & Verse Poetry Magazine, Cha (Hong Kong), and La Piccioleta Barca (Milan). She has collaborated with artists and writers in the UK, France, Spain, Germany, Portugal, North America, and Japan. In 2024, she will be an arts resident at the Tyrone Guthrie Centre in Ireland and Studio Kura in Kyushu, Japan. Visit her website for more information. [All contributions by Marsha McDonald.]