📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

Click HERE to read all entries in Cha on The Life of Tu Fu.

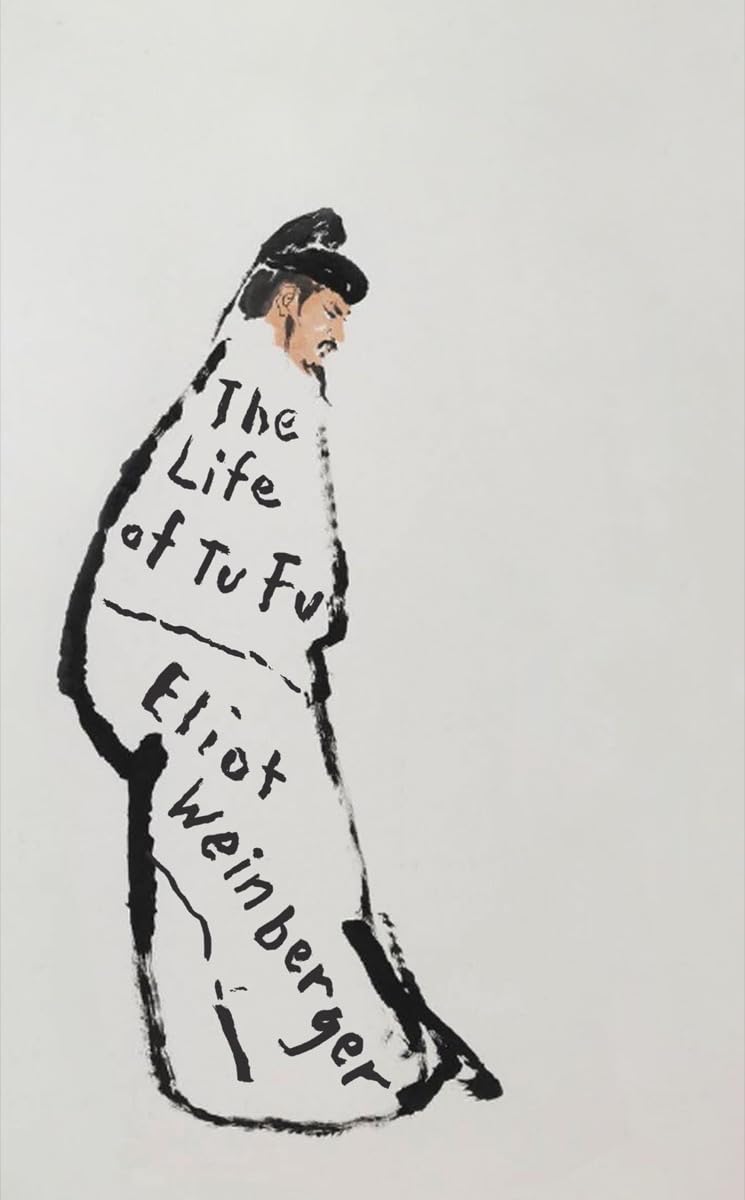

Eliot Weinberger, The Life of Tu Fu, New Directions, 2024, 80 pp.

In an author’s note on the last page of his new book The Life of Tu Fu, Eliot Weinberger explains that the project came to him when he was cooped up at home in New York City during the Covid-19 pandemic and working his way through the complete poems—approximately 1,400 in all—of the famous Tang Dynasty poet (c. 712–770).

Here it is, then: definitive proof that at least something good came out of the pandemic era.

In that same note, Weinberger immediately clarifies that this isn’t a book of translations but rather a “fictional autobiography” of the poet, “derived and adapted from the thoughts, images, and allusions in the poetry”. The autobiography takes the form of fifty-eight original poems that trace the outlines of Tu Fu’s life, from his time as a minor court official through the years he spent as an increasingly desperate refugee, fleeing for his life (sometimes with his wife and children, sometimes not) as China was wracked by a catastrophic civil war.

In a sense, this book of poems brings Weinberger full circle. As he explained to The New Yorker in 2016, he initially began translating Octavio Paz and other Spanish-language poets back in the 1970s, at the outset of his career, as a way of teaching himself how to write verse. But by the time he was thirty, frustrated by what he saw as his lack of an innate gift, he quit trying to come up with his own poems, realising instead that “I could take all of these things I had learned about writing poetry and use it to write prose”.[1] The result, as readers of Weinberger’s non-fiction know, is a style, fragmentary and allusive, that often reads like prose poetry.

That’s the voice we hear in The Life of Tu Fu. The book isn’t an act of literary ventriloquism—which would hardly be possible in any case, given that the source of Weinberger’s inspiration wrote in another language and lived more than 1,000 years ago. Instead, reading it frequently evokes the sensation of listening to a remix of a favorite piece of music, where familiar elements arrive in a new context. The horse without a rider gallops by, arrows sticking out of its saddle; the letters never arrive; peasant conscripts, cormorants, gibbons, even the famous hairpin all make an appearance. The voice can be haunted, rueful, even a little sly:

The only people I meet are people I’ve never known.

You’ll weep for reasons other than the war.

That last admonition is a tip-off that, like the American translator David Hinton’s 2019 collection The Selected Poems of Tu Fu, this book gathers steam as the poet’s circumstances grow more desperate and his country pitches further into extremity, with “all things caught between shield and sword” (a line from the poem Hinton translates as “Sleepless Night”).[2]

Part of what makes Tu Fu a timeless poet is his attentiveness to the effects of war on the lives of ordinary people. You may not be concerned with the history behind the rebellion and civil war that laid waste to a broad swathe of China in the eighth century, but Tu Fu makes you see and feel the misery of the exhausted peasant soldiers marching off to the frontier; of their wives, left to work the fields in their men’s absence; and of his own children, half-crazed from hunger as the family flees from one safe haven to the next. Weinberger honours this aspect of the poet’s vision with a series of spare, precise observations that land with special resonance in our current moment. “Everyone has cousins who died in the war.” “The corpses lying by the side of the road change so much in a single day.” And my own favorite, a perfect pairing of sentiment and image:

They win and we lose; we lose and they win.

Vines wrap around the rotting bones.

Readers can decide for themselves which country or countries that evokes for them in 2024—there are several options to choose among, which only demonstrates once again how Tu Fu is the “news that stays news” (Ezra Pound’s definition of literature seems especially apt in this context).

Juxtaposed with Tu Fu’s acknowledgment of human suffering, though, is his recognition of human evanescence. Even as they distil a moment in a place, his poems constantly point behind or beyond, to a broader canvas (we might call it nature) in which the cares of this world meet with complete indifference—and then vanish. “I write poems about what I see,” Weinberger has the poet tell us, “for things pass so quickly.” And later:

I write about what is happening:

I record the dawns and the sunsets.

The translator David Hinton devoted a whole book, Awakened Cosmos (2019), to explicating this bigger-picture aspect of Tu Fu’s art, which is evidently quite difficult to convey in English translation. As revealed in his poems, the universe’s indifference to our pain can be chilling; it can also be sublime. Weinberger gets the idea across with a minimum number of brushstrokes. “The sea accepts the water from all the streams.”

The Life of Tu Fu extends an engagement with Chinese poetry that stretches back decades. In 1987 Weinberger published 19 Ways of Looking at Wang Wei (second edition, 2016), a witty primer on the art of translation in which Wang Wei’s four-line poem “Deer Park” is revealed to be a sort of linguistic Rubik’s Cube: translators might get some or even most of the pieces to fall into place, but perfect alignment is a dream that stays forever just out of reach. Weinberger later compiled, introduced, and annotated The New Directions Anthology of Classical Chinese Poetry (2003), an introduction to a whole poetic corpus that also makes a cogent argument for the vital creative link between Chinese writers from hundreds of years ago and a major strand of twentieth-century American poetry. He also presided over the Calligrams series of reissues jointly published by the Chinese University of Hong Kong Press and New York Review Books, a set of titles that are indispensable for anyone interested in classical Chinese literary culture, and he has translated the contemporary poet Bei Dao.

Since Weinberger recently turned seventy-five and has now been publishing for half a century, it’s an opportune moment to note that the above achievements are just a few facets of a career that also includes seminal translations of Latin American poetry—like his rendering of the Chilean super-modernist Vicente Huidobro’s book-length poem Altazor, a high-wire feat that’s not as well-known as it should be—and, most importantly, a body of essays whose concision, intellectual breadth, and formal inventiveness have a way of making a lot of other people’s creative non-fiction seem a little beside the point. (And at a time when American-made bombs are again helping decimate one of the poorest populations on earth, one should acknowledge his forthright statements on U.S. foreign policy in What I Heard About Iraq and What Happened Here: Bush Chronicles.)

In all of Weinberger’s various guises—critic and essayist, editor, translator, and now, poet—his work demonstrates an exemplary commitment to cultural transmission: transmission across centuries, genres, languages. The Life of Tu Fu furthers that commitment through an act of elegant literary homage. In its modest way, it restores the link between Chinese classical tradition and present-day creative practice that Weinberger elucidated in his New Directions Anthology—and whose (apparent) passing two scholars of Chinese literature, Wiebke Denecke and Lucas Klein, lamented in a recent article.[3] You can read The Life of Tu Fu in an afternoon, but don’t be surprised if you find yourself picking it up again in the days afterward, and, having once started to browse, re-reading it all the way through to the end. (Also: In keeping with New Directions’ usual production standards, the pamphlet-sized paperback is an irresistible physical object.) Readers can be grateful that Eliot Weinberger, like Tu Fu before him, found creative inspiration in dismal events, or “what [was] happening.”

NOTES

[1] Christopher Byrd, “The Unclassifiable Essays of Eliot Weinberger”, The New Yorker, Dec. 14, 2016, https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/the-unclassifiable-essays-of-eliot-weinberger.

[2] The Selected Poems of Tu Fu, tr. David Hinton (New York: New Directions, 2019).

[3] Wiebke Denecke and Lucas Klein, “Launching the Hsu-Tang Library of Classical Chinese Literature on the 250th Anniversary of the Complete Library of the Four Treasuries”, The Journal Of Asian Studies, 82:2, May 2023, DOI: 10.1215/00219118-10290650.

How to cite: Tompkins, Jeff. “He Records the Dawns and the Sunsets: Eliot Weinberger’s The Life of Tu Fu.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 17 May 2024, chajournal.blog/2024/05/17/tu-fu.

Jeff Tompkins is a writer and zine artist in New York City. His articles and reviews have appeared in The Brooklyn Rail and Words Without Borders, among other outlets. [All contributions by Jeff Tompkins.]