TH: Suo Er read part of this essay at the “Nature on Edge” panel at the Iowa City Public Library on Friday 8 September 2023, as part of the Iowa Writing Program Fall 2023.

I’m not joking when I say that, until I was seventeen years old, I’d never set foot outside of my hometown—which is as small as Faulkner’s postage-stamp-sized Yoknapatawpha. Faulkner’s fictional town of Yoknapatawpha gets its name from Chikashshanompa, the language of the Chickasaw tribe. Yoknapatawpha translates as, “the river flows slowly through the flat land” (Yok’na pa TAW pha), a description that reminds me of my hometown, where six-and-a-half-million years ago lava flowed and ash transformed the terrain into vast maritime plains, where volcanic eruptions birthed hills and erosion worked together with the tropical climate to create a thick, rust-red layer of soil. My young mind saw the flat land of my hometown as a red mirror. For as long as I can remember, my father would take me on a hike or for a ride on the back of his motorbike, through the gleaming ponds, patchwork fields, and scalding coastal roads. That’s probably when the seed of curiosity that later grew into my interest in nature was planted in my mind. Perhaps because of familiarity or a native emotion, before I left my hometown, I naively thought that the rest of the world would be just like it, with its red plains, its unfading banyan and coconut trees and banana groves, its damp sea breeze that always smelled of fish, and its endless drought with an oppressive heat hovering overhead.

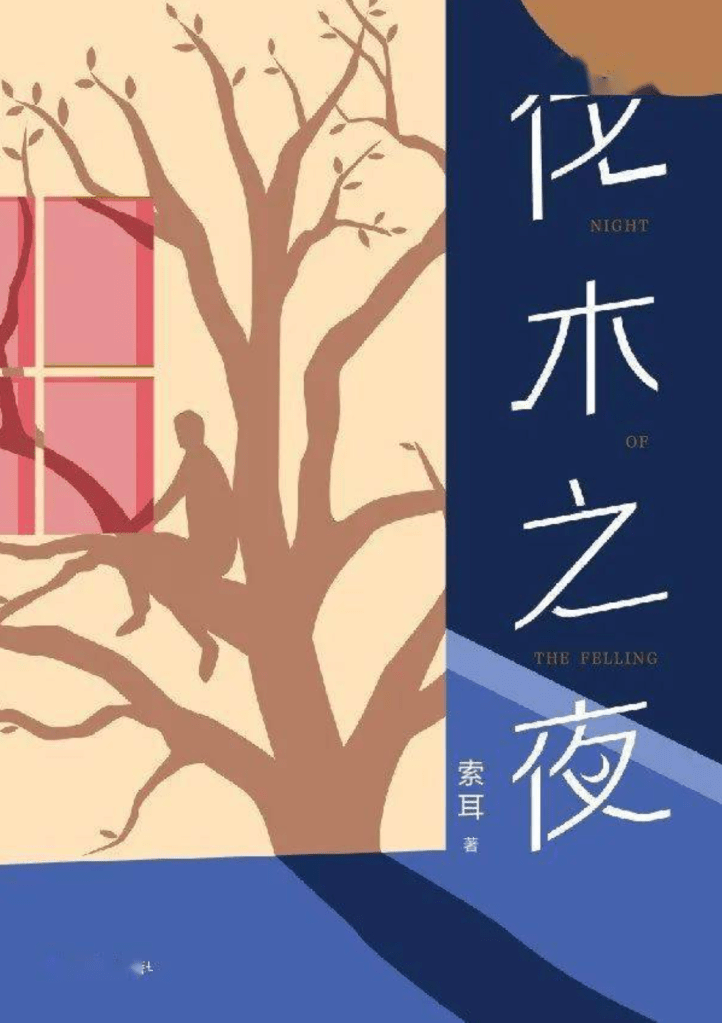

People’s early childhood memories are valuable. Whether they see in the decades that follow mountains and canyons, immortal bones preserved in Arctic ice, or the iron dust that flies on Mars, what remains in the deepest part of one’s consciousness is the landscape as recorded by the eyes of a child. It’s like a bomb, you don’t know when it might be suddenly detonated. My first novel, Night of the Felling, takes place mainly in a lychee forest. To be honest, I didn’t have any particular reason for choosing the image of a lychee. I only remember that when the idea first came to me, I was on the train home when we slowly passed through a lush lychee forest. Those branches and dark green leaves mingled with the afternoon sun to reveal a shining, warm quality. In that moment I was shocked by their vitality, and the sleepiness from travelling for eight or nine hours was swept away. I thought, I was born here. I’ve seen lychee trees before, but never have they been so beautiful. Why don’t I write a novel with lychee trees? So when I looked back after writing, taking my time, flipping through the pages again and again, completing, revising, and publishing, I suddenly realised: what image matches Lingnan better than a lychee grove? It’s something that’s here and nowhere else. Its reputation cut through the thick, toxic air, or 瘴气, that had surrounded Nanling as early as the Tang Dynasty, 1300 years ago. In the era before refrigeration and express deliveries, horses carried lychees thousands of miles to the imperial palace of the Central Plain dynasties in Zhongyuan, as a treasure for aristocrats to taste.

In the novel, I write:

我紧跟在他后面走,跟着他不断地在枝干间绕圈。我仍然觉得举步维艰。但其实植株间的距离是一致的,从外边到里面,不存在越种越密的情况,我明白。过了一会,我的头顶、脖子边、肩膀上、胳肢窝、腰间、大腿边和膝盖边仿佛都长出了荔枝叶子。在可见的范围里,成片的树叶像是镀上一层厚蜡,把绿的色彩变得不那么尖锐,就算是反射着阳光,也不会显得太过刺目,而是给人以钝重、沉静的感觉。有些枝干肆意地往四周扩散,像漆黑的八爪鱼的腿,八根腿里面有的呈直线上升、有的呈曲线垂下,有的呈水平角度向左或右拐弯,相互间紧紧交缠在一起。它们这种生命力有点太让人嫉妒了。

(I walked closely behind him, following him as he circled around and around between the branches. I still find it hard to walk. But the distance between the plants is the same, and I come to understand that the trees in forests don’t grow closer together the farther in you go. After a while, it seemed as if the leaves of the lychee trees were growing all over me. From my head, neck, and shoulders, from my armpits, waist, thighs, and knees. From what I can see, it’s as if the leaves are coated in a thick layer of wax, dulling their green colour. Even if it were to deflect the sun’s rays, it wouldn’t be too striking, but rather would give me a blunted, gentle feeling. Some branches stretched in all directions like the legs of a dark-coloured octopus while some stood as straight lines; some hung in curves while some were leveled with the ground—their ends pointing to the left and to the right—tightly intertwined. Their vitality a little too enviable.)

In another of my short stories, The Female Heir, I use the typhoon to develop the plot, creating an unspoken misunderstanding between the two heroines. Although it may not stand out among the thousands of China’s southeast coast typhoon narratives, a typhoon is difficult to imagine for those who have lived inland for a long time, especially on the more subtle, spiritual level. It’s like when I went to big cities in the north when I was an adult; I marvelled at how those trees grew to heights that the trees in my hometown would never reach, torn apart as they were by the typhoons that blew in from the Pacific every summer and autumn. Those typhoons are all given strange, foreign names—much like the monsters that brought about the fall of the gods in Norse mythology. Every time they crossed the border, the streets would be littered with the broken limbs of trees. As a child, I didn’t understand the feelings of the farmers whose crops had been destroyed, among them member of my own family! I’d get excited every time the weather observatory forecast a typhoon, because it meant school would be cancelled. Even though I couldn’t play outside, at least I was free from the torment of schoolwork for a day or two. As per usual, the typhoon would create a power outage, so we would spend the stormy night chatting, swaying shadows from the flickering candlelight on the wall. For our simple family of three, those were a precious “State of Exception” and moments of intimacy.

Interestingly, when I shared this experience with a friend from the southwestern Hengduan Mountain region, she blinked and offered her own narrative, one of a life in a landlocked town, in reply. When she was at school as a child, sudden earthquakes would interrupt her classes. The chalk on the lectern would clatter around and even fly onto the blackboard. Then the teacher would usher everyone to the playground. She’d squat or sit just like those around her, her body pressed against the earth as she felt the throbbing of the earth’s heart from hundreds of kilometres away.

This was her/their “State of Exception.”

I majored in geography in college, but after all these years, I have long since surrendered this knowledge, handing it back to my teachers. One of the few who made an impression on me was the geography teacher. He was a short, stocky, balding, and often cheerful man who was nearing retirement, but once during class he said, in a firm and dignified manner: “I can guarantee that there will be no major earthquakes in Guangdong in the next 500 years.” Why 500 years? Why would he make such a guarantee? I’m reminded of my childhood in the 1990s, when I survived a few “non-existent earthquakes.” These weren’t actual earthquakes, but periodic panics during a backward age of information deprivation. Every once in a while, a neighbour would knock on our door in the middle of the night. My parents would drag me, dazed and panicked, out of bed and downstairs to escape the “earthquake”; all while the others continued to knock on people’s doors and drive them out of their apartments. Then everyone would wait for the earthquake, together in that downstairs open space, until daybreak when they’d disperse. I wrote about this in Weekend with Dr Uranium.In 1960s and 1970s rural China, people run out in the middle of the night to avoid a non-existent earthquake, imagining their belongings being upended and thrown into the air, rearranged, and then redistributed to their owners. They aren’t waiting for an earthquake; they’re waiting for a new order.

Maintaining order across China’s vast territory has historically been a far from simple matter. In more academic terms, an ancient agricultural civilisation centralised its empire in the central plains of northern China. As its influence stretched further from the center, its power weakened. It’s no coincidence that this sounds like the ”Differential Mode of Association”—a theory conceived by the famous anthropologist, Fei Xiaotong, to describe human relations in China. From this framework, we can understand how it was that people in the south—far from the centre of the empire—were regarded as uncivilised barbarians. However, at the same time it’s the geography that allows the more compete preservation of diverse ethnic groups and their cultures. Thus is the distinction between “centre” and “edge”. Looking at the edge from the centre of the empire, it is a land drenched in 瘴气, its mountains and rivers a labyrinth. “瘴气” is a very magical thing. A thing of legends dating back to before the era of science, it was said to be a mixture of water vapor and poisonous gas from mountains and swamps, and of the fetid gas from rotten corpses. It enveloped the entirety of southern China, terrifying the scholars who had been exiled from the Central Plains. Without a doubt, 瘴气has shrouded in mystery demons and monsters from fantastical tales, as well as our faith in ancestors and God. Historically, 瘴气 has served as both a ward against northern invaders, and as rich nourishment for native plants— living in the margins, fresh and vivacious.

Over time, our view of the South has lost its charm. Especially with the rise of natural history in the west during the 18th and 19th centuries. When visitors from overseas entered southern China through Guangzhou, their senses were overwhelmed by this unfamiliar plant kingdom, brimming with a variety of plants native to the area. They collected seeds, prepared specimens to ship home, catalogued them, and then confidently used their modern knowledge and technology to interpret and explain their discoveries. But would they understand the generations of stories told by the blind underneath the banyan tree? Would they understand the tale of the demon manifested from the banana forest’s Yin energy? Would they understand the ritual of bathing children in pomegranate flowers and smilax grass once they’d grown up?

As I walked along China’s southern shore, I overheard a most fascinating story. In coastal fishing towns, each family has its own plot of sea, just like farmers have their own plots of land. But unlike on a farm, there’s no visible boundary separating these “sea fields” from one another. And yet, these “sea farmers” know where their plot begins and ends, because in their minds is a sea chart as a result of their daily life living with it.

So let me ask you, do you have a sea chart in your mind?

How to cite: Suo Er and Grace Najmulski, “Do You Have a Sea Chart on Your Mind?.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 19 Oct. 2023, chajournal.blog/2023/10/19/sea.

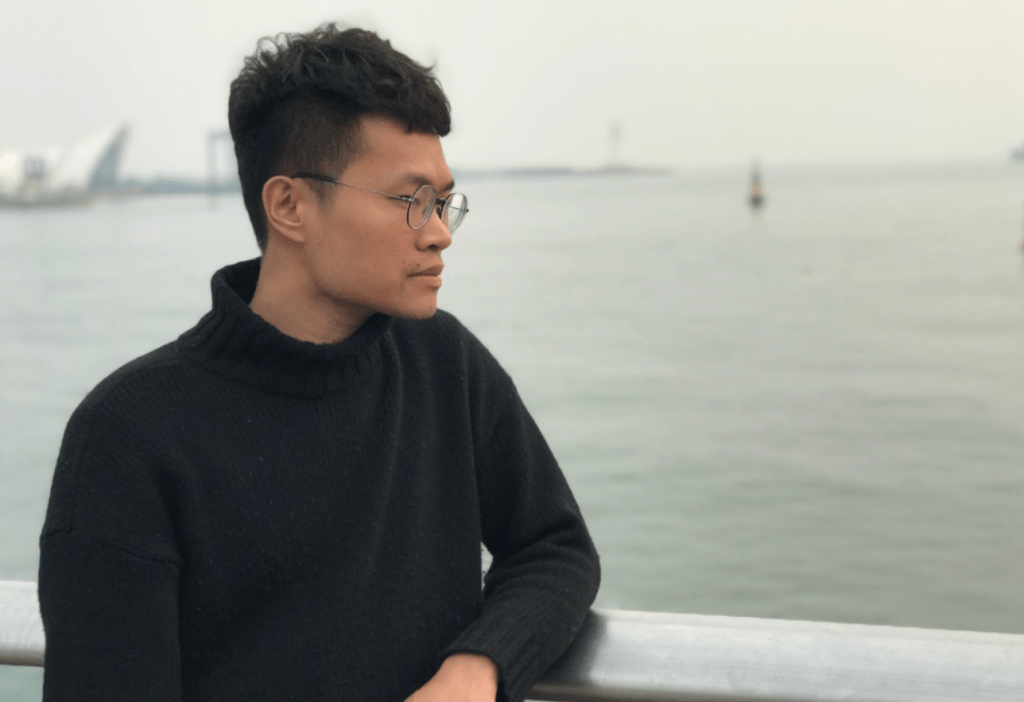

Suo Er (poet) is the author of the novel Night of the Felling《伐木之夜》and the story collection Noncorrelation 《非亲非故》. His works have appeared in China’s top literary magazines and received many awards, the 43rd Hong Kong Youth Literary Award and a 2021 nomination as Most Promising Newcomer of the Year by the Southern Literature Festival among them. He has also engaged in publishing, media, and exhibition work. His writing concerns itself with the dispersion of cultures, and with lives of individuals in a “Southern framework.”

Grace Najmulski (translator) is a second year at the University of Iowa’s MFA in Literary Translation who translates from Chinese (simplified and traditional characters) and Japanese. They learned both languages in their undergraduate studies at Middlebury College after a YOLO moment made them decide to major in both. Inspired by the words of Gayatri Spivak, they hope to challenge English language norms by introducing the beauty of other languages in their translations. Very anti-colonialist spirit. Hobbies include: reading, bookstagram, badminton, eating, napping, rewatching the same shows on Netflix, and worshipping their cat (what a cutie patootie). This is their first time having their work published. [All contributions by Grace Najmulski.]